Biodiversity, conservation, and Indigenous Peoples’ well-being

In Canada and around the world, protected areas and conservation actions have often been informed by non-Indigenous worldviews, viewing the natural environment as one with limited contact by humans. This approach contributed to impoverishing Indigenous Peoples, who also had to face complex socio-economic issues. Because Indigenous health, livelihoods, and well-being are intrinsically linked to the health of nature, transformative changes were needed to restore and protect nature in ways that would also strengthen the health and well-being of Indigenous Peoples.

Key facts about Canada’s forests and Indigenous Peoples

In Canada, almost 5% of the population identify as an Aboriginal person, and almost 70% of them live in or near forested lands.

The culture and economy of more than 200 language groups are strongly interconnected with the land.

When local people are empowered to manage and restore forests, forests are more resilient with positive impacts on biodiversity and socio-economic benefits for the communities.

Resilient forests are able to withstand or recover quickly from disturbances or new conditions.

Over the last two decades, there has been a wind of change with greater recognition and commitments to reconciliation and respect for Indigenous rights in Canada under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and also following the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). In response to Calls to Action, the UNDRIP became a law in 2021 and states that “Indigenous peoples have the right to the conservation and protection of the environment and the productive capacity of their lands or territories and resources” (article 29.1).

At the same time, efforts have been made to meet international conservation targets, such as those set out in the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Canada is also committed to addressing climate change. It has been recognized that conserving, protecting and restoring nature are the best nature-based solutions to mitigate its impacts, and that collaboration with Indigenous Peoples is essential in this endeavour. As the Government of Canada aims to designate 25% of the land as protected space by 2025 and 30% by 2030, advancing Indigenous-led conservation and new ways to collaborate is critical to meet these ambitious targets.

Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas: A new path to promote Indigenous-led conservation and reconciliation in Canada

In 2017, Indigenous government representatives, Elders, and a range of land users added their voices to establish the Indigenous Circle of Experts with the aim to define new Indigenous-led conservation initiatives: the Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCA). The goal was to promote and inspire Indigenous leadership to make conservation decisions for land and water, but also to recognize and address the consequences of colonization in terms of parks management and protected areas. Therefore, IPCAs aim to fill multiple gaps in addition to conservation goals such as the need to advance reconciliation actions and to create collaboration, respect and sharing across the Indigenous and western cultures. IPCAs will then contribute to advance conservation efforts from an Indigenous perspective and restore Indigenous knowledge systems that have historically been disregarded and sometimes criminalized.

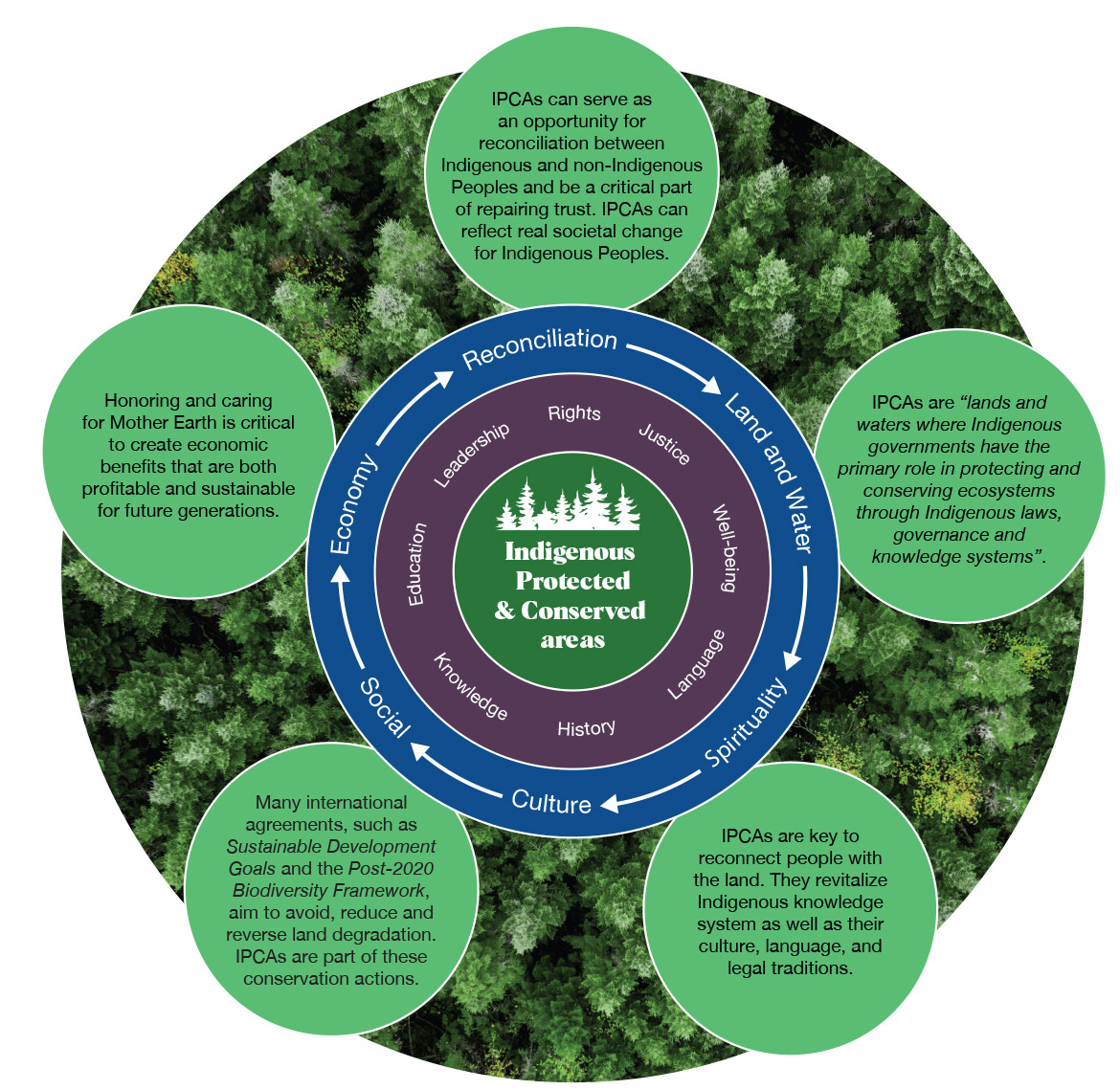

The objectives of an IPCA are multiple and aim to restore and preserve Indigenous leadership, their environment, culture and knowledge systems. (Image was modified from Mansuy et al., submitted)

Scaling up Indigenous-led conservation initiatives

Canada has one of the largest land masses and Indigenous populations in the world. IPCAs can thus contribute significantly to conserve both the environment and Indigenous Peoples’ culture. To support these conservation efforts, the Government of Canada has put in place the Indigenous Guardians Program that provides funding for Indigenous Peoples to exercise greater leadership and stewardship in protecting and conserving their traditional lands. Since 2018, three terrestrial IPCAs, Saoyú-ʔehdacho, Thaidene Nëné, and Ts’udé Nilįné Tuyeta, have been formally established under the Protected Areas Act. They are all located in the Northwest Territories and have a total area of 24,715 km2, or the size of Lake Winnipeg. In Budget 2021, the Government of Canada announced up to $100 million over five years (2021–2026) to support new and existing Indigenous Guardians initiatives and could position Canada as a leader in Indigenous-led conservation. To date, more than 50 Indigenous communities across the country have received funding to either establish IPCAs or undertake early planning and engagement work that could result in additional IPCAs.

Collaboration is key for protecting natural environments in Canada

Because the IPCAs are in their infancy, there is a unique opportunity to combine community-based knowledge and expertise with western science to protect and restore resilient ecosystems. The Canadian Forest Service (CFS), along with Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) and Parks Canada, is working with Indigenous leaders and scholars to support community and Indigenous-led conservation efforts to achieve these goals. Examples of engagement include collaboration with Dene Tha’ First Nation, located on Treaty 8 in the Province of Alberta and the University of Alberta to ensure that conservation efforts are implemented following Indigenous values and way of life. The University of Alberta is also leading the Ărramăt project, involving more than 150 Indigenous organizations around the world and following the principles of reciprocity, recognition, and reconciliation.

Collaboration is key to bridging different knowledge systems and visions of the ecosystems and the ecological services they provide. Given the different values and uses of the territory, collaboration between multiple stakeholders and land users is also important to develop more holistic and interdisciplinary approaches. Holistic approaches view both biodiversity conservation and human well-being as interdependent and equal, and are therefore essential to achieving the multiple benefits of IPCAs (ecological, socio-economic and cultural). In the face of climate change and rapid land-use changes, working with Indigenous Peoples is fundamental in developing adaptive approaches that integrate the multiple ecosystem services and values into conservation management. As the need to protect biodiversity becomes increasingly urgent, so too does the need to promote Indigenous Peoples’ role as stewards of the land, and to support various Indigenous-led conservation measures.

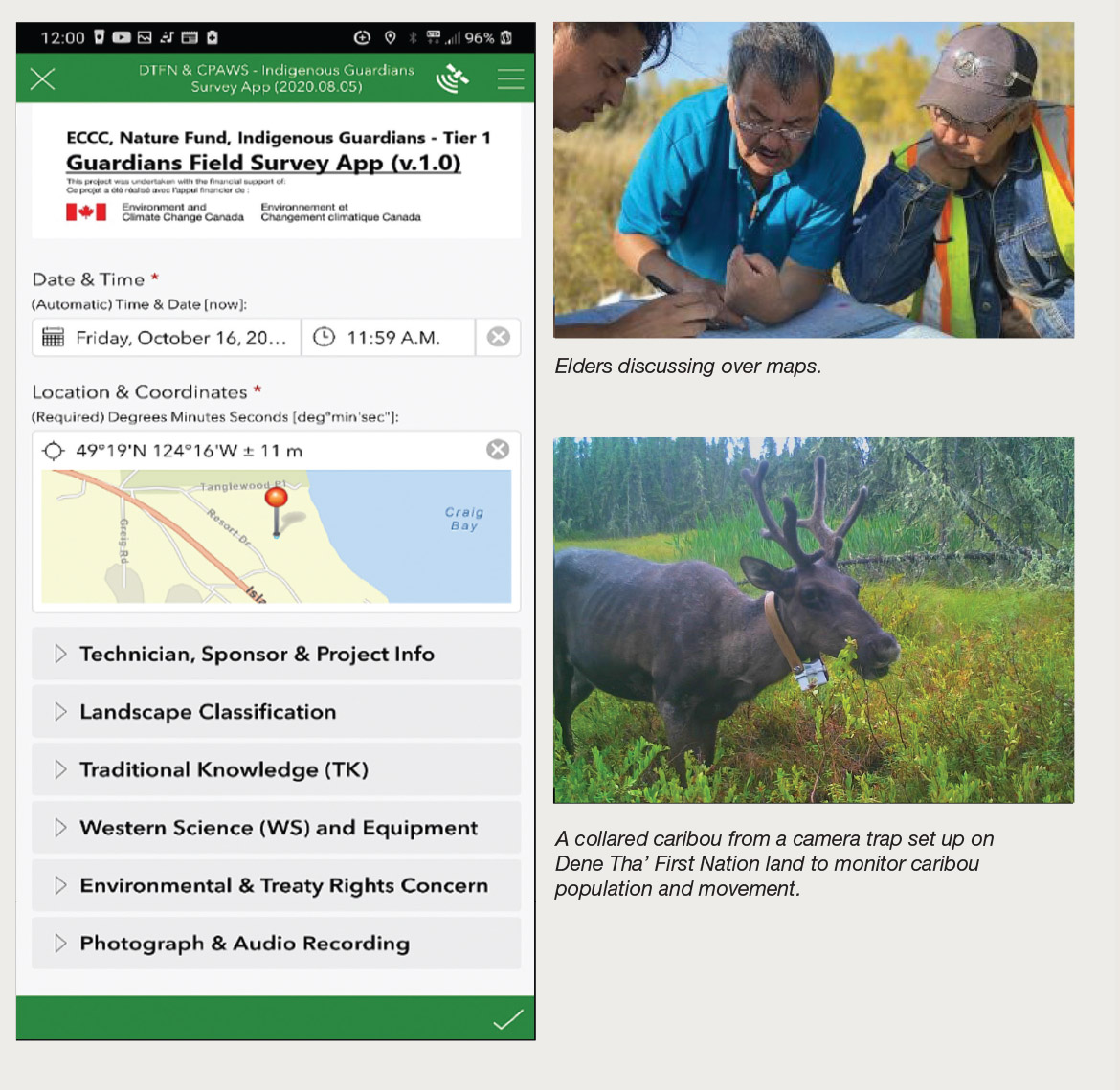

Western science and traditional knowledge are combined in the Bistcho Lake IPCA project led by Dene Tha’ First Nation in collaboration with the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS). This collaboration resulted in the creation of the Indigenous Guardians Survey App that can localize and classify traditional knowledge into a geodatabase. This project was funded by the Guardian Program of ECCC and the CFS. (Image was modified from Mansuy et al., submitted. Photos are courtesy of Dene Tha’ First Nation)

Page details

- Date modified: