Evaluation of Forest Ecosystems Science and Application Program Sub Activity

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Acronyms

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Program Background and Profile

- 2.1 Context

- 2.2 Mandate and Stakeholders

- 2.3 Governance and Administration

- 2.4 Activities, Delivery and Organization

- 2.4.1 Forest Biodiversity

- 2.4.2 Forest Carbon Research, Reporting and Policy Advice

- 2.4.3 Assessing and Understanding Ecosystem Productivity and Dynamics in Support of Sustainable Forest Management

- 2.4.4 Global Leadership in the Development of the International Model Forest Network (IMFN)

- 2.4.5 National Forest Information and Assessment (NFIA)

- 2.4.6 Reclamation of Disturbed Forest Landscapes

- 2.4.7 Distribution of components by project area

- 2.5 Funding and Resources

- 2.6 FESA Logic Model

- 3.0 Evaluation Objectives, Scope, and Methodology

- 4.0 Evaluation Findings

- 5.0 Conclusions and Recommendations

Tables

- Table 1 FESA Program Sub-Activity stakeholders

- Table 2 Activities and outputs expected for the Biodiversity project area

- Table 3 Activities and outputs expected for the Carbon project area

- Table 4 Activities and outputs expected for the Productivity & Dynamics project area

- Table 5 Activities and outputs expected for the IMFN project area

- Table 6 Activities and outputs expected for the Forest Assessment project area

- Table 7 Activities and outputs expected for the Land Reclamation project area

- Table 8 Number of components by project area, 2007-08 to 2011-12

- Table 9 Summary of internal and external expenditures, by FESA project area and overall, 2007-08 to 2011-12 ($ millions)

- Table 10 FESA Financial Expenditures by type and by project area, 2007-08 to 2011-12 ($ millions)

- Table 11 Overview of evaluation data collection methods

- Table 12 Peer-reviewed scientific output in Forestry, 2003–2011

- Table 13 CFS output by FESA project area and document type, 2003–2012

- Table 14 CFS publication output by FESA project area and CFS research centre, 2003–2012

- Table 15 Result of webpage usage study for eight selected peer-reviewed papers

- Table 16 Selected CFS grey literature documents, produced between 2003 and 2012, with most Google hits per FESA project area

- Table 17 Webmetrics results for selected FESA non-publication outputs

- Table 18 Result of webpage usage study for eight selected non-publication items

Figures

- Figure 1 FESA Program Sub-Activity Logic Model

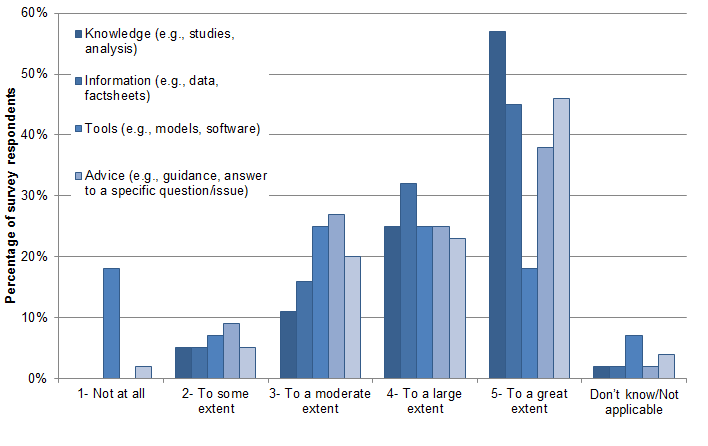

- Figure 2 Specialization(*) patterns of Canadian sectors within Forestry across FESA project areas, (A) 2003-2006 and (B) 2008-2011

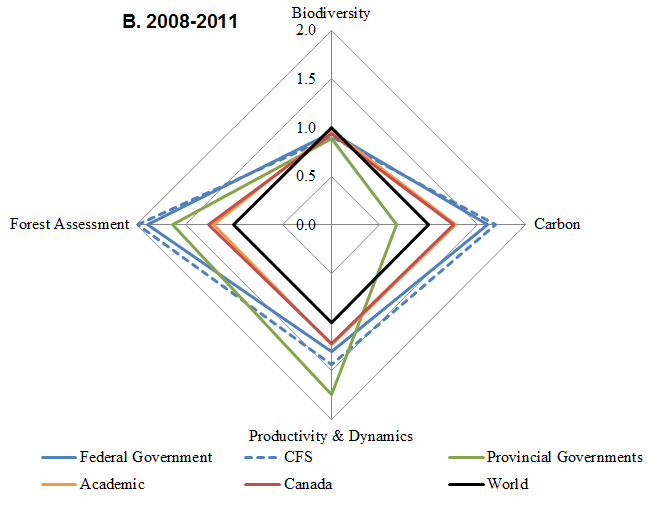

- Figure 3 Main types of outputs identified by FESA component leads

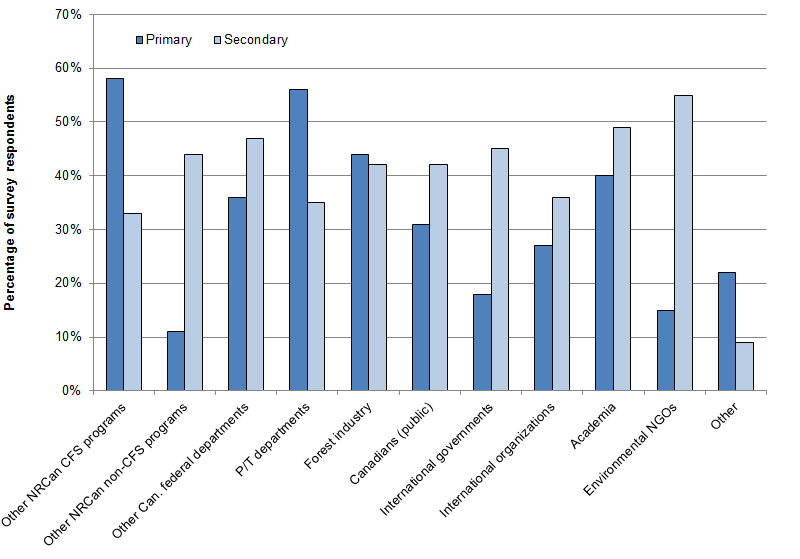

- Figure 4 Primary and secondary target audiences for FESA outputs

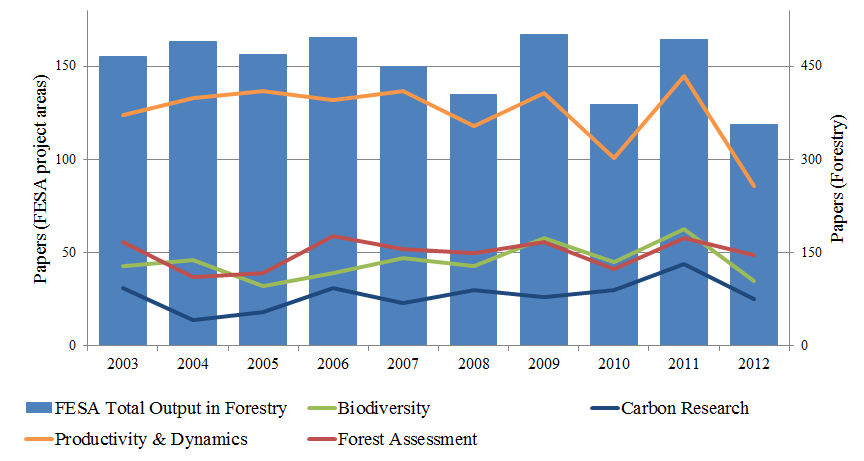

- Figure 5 CFS publication output by FESA project area and year, 2003–2012

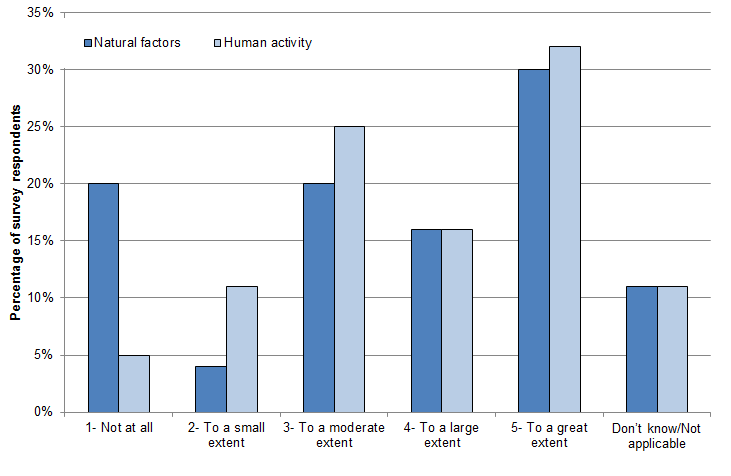

- Figure 6 Extent to which FESA components contribute to understanding forest ecosystem responses to natural factors and human activity

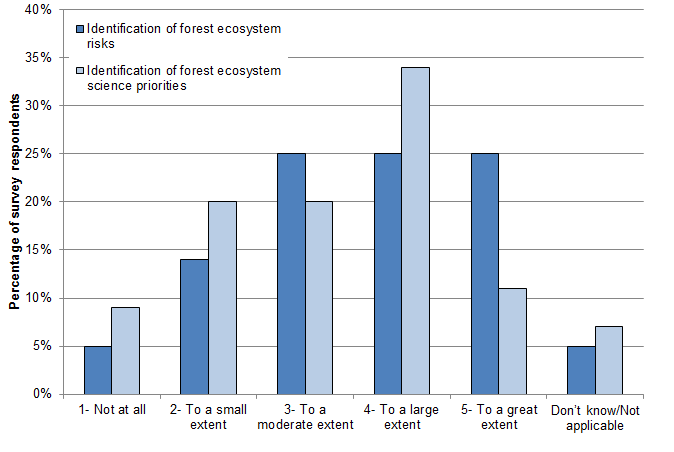

- Figure 7 Extent to which FESA components contribute to identifying forest ecosystem risks and science priorities

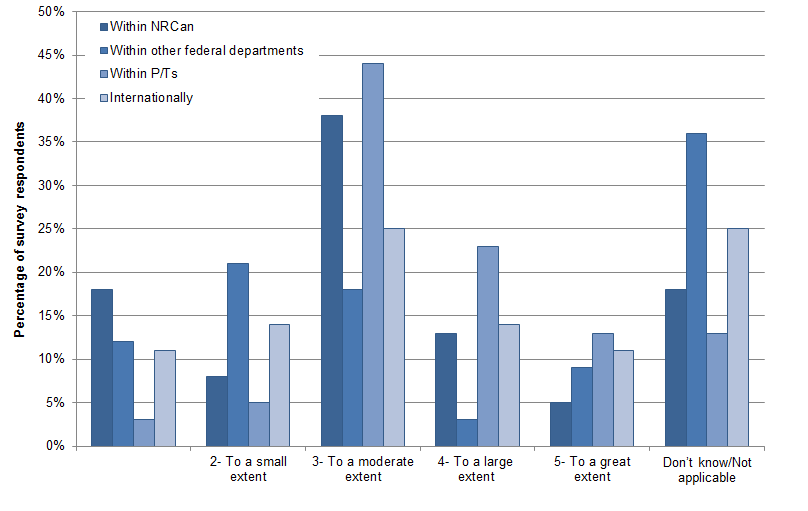

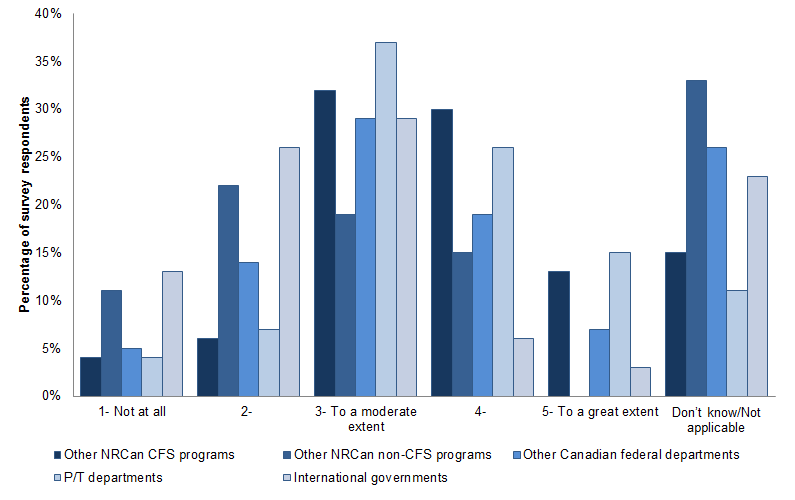

- Figure 8 Extent to which target audiences use FESA outputs to manage forest ecosystems, and forecast and manage forest ecosystem risks

- Figure 9 Extent to which target audiences within governments use FESA outputs to inform decisions that improve forest ecosystem management policies and practices

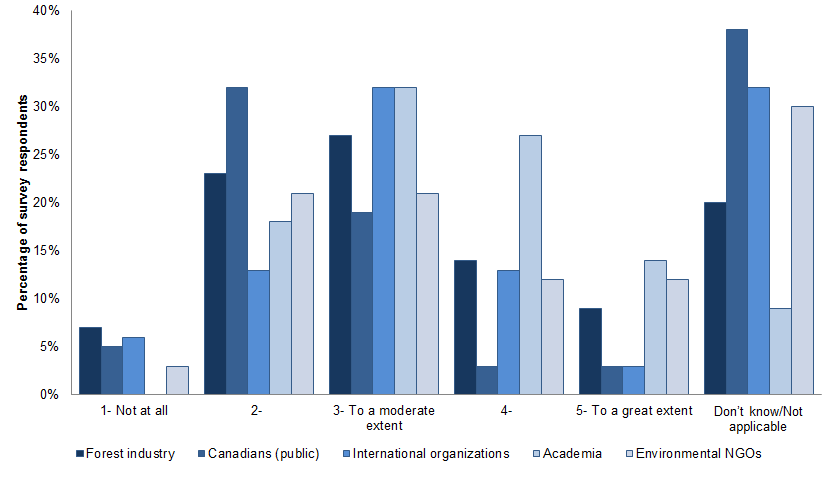

- Figure 10 Extent to which non-governmental target audiences use FESA outputs to inform decisions that improve forest ecosystem management policies and practices

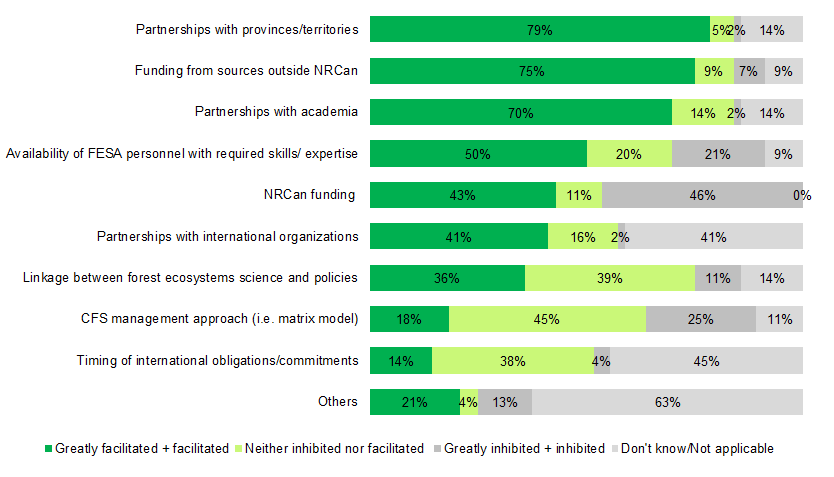

- Figure 11 Factors facilitating or inhibiting achievement of FESA outcomes

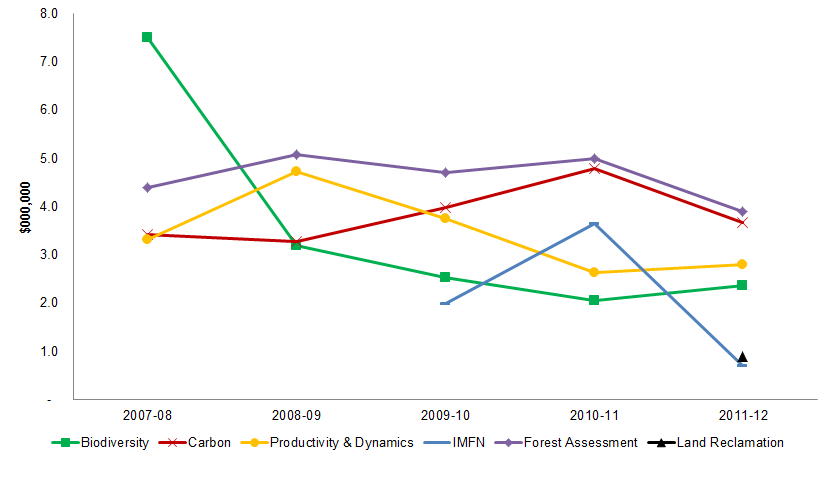

- Figure 12 Trends in internal resources by project area, 2007-08 to 2011-12

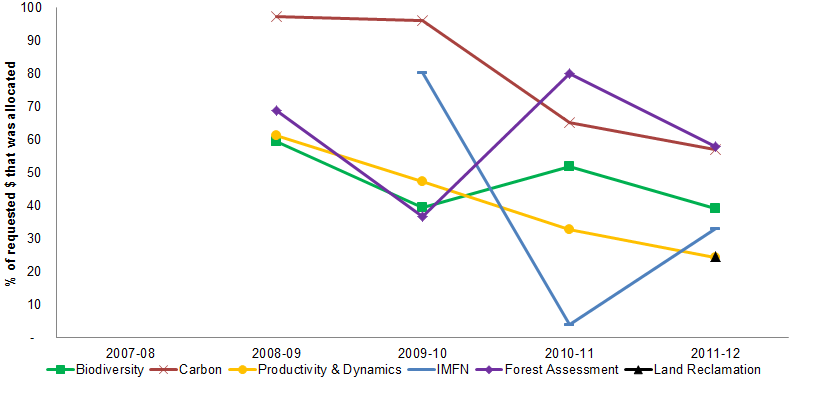

- Figure 13 Trends in internal resources allocated as a percentage of funding requested, by project area, 2007-08 to 2011-12

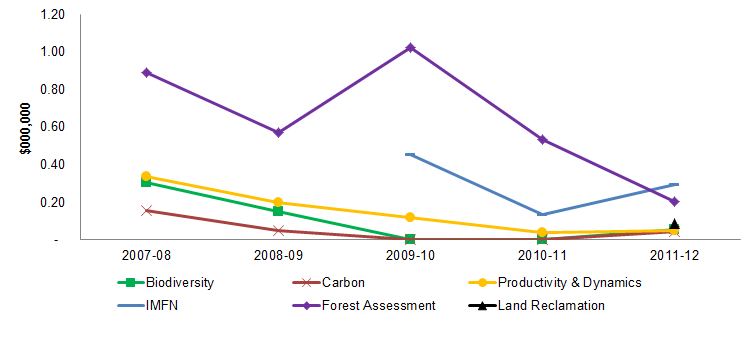

- Figure 14 Trends in external financial resources by project area, 2007-08 to 2011-12

Acronyms

Executive Summary

Introduction

This is an evaluation of the Forest Ecosystems Science and Application (FESA) Program sub-activity for the period 2007-08 to 2011-12. FESA was established with the objective to increase scientific knowledge on forest ecosystems and support stakeholders in their sustainable forest management (SFM) policies and practices. As part of Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), FESA conducts research, national assessments and monitoring to develop, synthesize and integrate scientific knowledge. This knowledge is used by the appropriate government jurisdictions, industry, and other stakeholders to develop forest management practices and policies, and by NRCan and other federal government departments, to meet international reporting obligations, from Canada’s negotiating positions on international environmental issues related to forests, and counter misconceptions of Canada’s forest practices. This work is conducted by the Canadian Forest Service (CFS) within NRCan.

During the evaluation period, this Program Sub-Activity consisted of the following six project areas: 1. Forest Biodiversity; 2. Forest Carbon Research, Reporting and Policy Advice; 3. Assessing and Understanding Ecosystem Productivity and Dynamics in Support of Sustainable Forest Management; 4. Global Leadership in Development of the International Model Forest Network (IMFN); 5. National Forest Information and Assessment (NFIA); and 6. Land Reclamation.

Note that FESA also encompasses a regional delivery model, with work carried out in the National Capital Region, as well as in five different forestry centres in Canada. Expenditures for delivery for the FESA Sub-Activity totaled $101.5 million from 2007-08 to 2011-12, including $84.4 of NRCan expenditures, $5.7 million in external financial resources (actual) and $11.4 million in-kind support (planned).

Evaluation Scope, Objectives and Methods

This evaluation was mandated by NRCan in accordance with the Federal Accountability Act, the 2009 Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation and NRCan’s Strategic Evaluation Division’s evaluation policies. The primary objective of the evaluation was to assess issues relating to the relevance and performance of the FESA Program Sub-Activity and provide recommendations as necessary.

All six project areas were covered by the evaluation, with the exception of the African Model Forest Initiative, a Contribution program within the IMFN project area, which will be assessed as a separate evaluation. The FESA evaluation followed a theory-based approach, in which emphasis is placed on the process by which the Program arrives at its expected results.

The evaluation was designed to draw on various sources of data to ensure that the combined lines of evidence resulted in an in-depth and comprehensive analysis. The five methods used to collect and analyze evidence were: 1) a document file and data review; 2) a review of CFS ProMIS planning database; 3) stakeholder interviews and focus groups; 4) an online survey of project area component leads; and 5) bibliometrics and webmetrics.

Evaluation Findings

Relevance

Continued need for program: FESA remains highly relevant, addressing several ongoing needs. FESA provides the unique and long-standing expertise and specialization in forest ecosystem science that are particularly relevant to address environmental issues and to support forestry sector competitiveness. Ongoing needs for each of the six FESA project areas were also identified by the evaluation. However, CFS should clearly define its niche with respect to the Land Reclamation project area.

Alignment with federal roles and responsibilities: The evaluation found that FESA plays a legitimate and key role, gathering and reporting national information used by a wide range of target audiences, as well as building a long-term perspective. CFS provides unique scientific expertise and research and complements those outputs from provinces/territories and academia. Furthermore, the federal government is mandated to represent Canada’s global interests and address international obligations relating to forestry.

The alignment of the IMFN and Biodiversity project areas to FESA requires further clarification. The IMFN as a platform to import forest management knowledge and experiences is relevant to more than one Sub-Activity Program, including FESA. Therefore, there may be an opportunity to position IMFN as a platform for disseminating horizontal CFS scientific research on sustainable forest management. Regarding Biodiversity, its integration into a new project area (Ecosystems Integrity) has helped clarify and focus the scope of research to be conducted; however, this has resulted in biodiversity expertise that is perceived by some NRCan interviewees to not be fully integrated within the new project area. There is an opportunity to further assess whether the biodiversity research or expertise developed over the last five years has been adequately integrated into the Ecosystems Integrity project area.

Alignment with government priorities: FESA was consistent with both federal government priorities and NRCan strategic outcomes throughout the evaluation period. Federal priorities over the evaluation period consistently displayed a commitment to developing the forest industry. FESA was also aligned with NRCan goals to remain environmentally responsible as outlined in the Program Alignment Architecture (PAA).

Performance

Achievement of expected outcomes: The FESA project areas have been generally successful in producing high quality outputs, which have been accessed and used by a wide range of target audiences. The work of CFS is regarded as credible and science-based such that provinces/territories often use FESA information or expertise to fill their own capacity gaps. FESA has also realized immediate outcomes and contributed to some intermediate level outcomes. FESA activities have contributed to an increased understanding of how ecosystems respond to natural factors and human activity, have supported domestic policy making and improved forest management practices, and have contributed to Canada meeting its national and international obligations. While the evaluation could not clearly determine the extent to which FESA information is used to forecast and manage ecosystem risks, the existing evidence suggests that FESA does moderately contribute to some risk management activities.

The Sub-Activity’s stakeholders were generally satisfied with the accessibility of FESA outputs; however, some opportunities for improvement were identified with respect to the communication and usability of these outputs and the need for more direct interactions with stakeholders.

Importantly, during the evaluation period, CFS has increasingly oriented its science towards policy priorities within available resources. This is likely to have an effect on capacity, expertise, and services historically made available to traditional end-users, as well as regional partners. The evaluation finds that to date, these changes have been effectively implemented internally, but not well-communicated to users.

Demonstration of efficiency and economy: Collaborations, partnerships and close working relationships were found to greatly facilitate the achievement of outcomes and enhance external leveraging. Support from external resources (funding and in-kind) often made up the difference between the requested and allocated internal resources in several project areas. This is significant considering that internal resources have declined overall during the evaluation period.

Considering the synergistic working relationships between CFS and its traditional users, there is a need for FESA to communicate to its stakeholders any changes in its services, including those due to an increasing focus on science-policy integration.

Declining resources also posed a challenge to supporting access and use of FESA information by external stakeholders. Lack of public science dissemination and/or communication of new tools or outputs meant that users were not always aware of FESA achievements or that FESA outputs were not in the best format to be efficiently used.

Although there are management procedures in place to support the achievement of FESA outcomes in an economical and efficient manner, there is currently no systematic performance data collection or progress reporting process. Given that this is a sub-activity of national scope with diverse project areas and target audiences, improving the priority-setting process and enhancing the ProMIS system could allow for better performance tracking and hence more informed decision-making.

Recommendations and Management Response

The following Table presents six recommendations, based on the findings, and the management responses.

| Recommendations | Management Response/Action Plans | Responsible Official/Sector (Target Date) |

|---|---|---|

| Recommendation 1: It is recommended that NRCan further examine the relevance of FESA’s role in the International Model Forest Network and Land Reclamation. CFS should explore opportunities to position IMFN as a platform for disseminating CFS scientific research and knowledge on sustainable forest management. CFS should also clearly identify the objectives and key research questions that Land Reclamation needs to address. | Agreed. Actions to address the recommendation: (i) The CFS agrees to further capitalize on IMFN as a FESA project aiming at communicating CFS science and disseminating knowledge on sustainable forest management policy and practices. In particular, all opportunities across CFS programs for using IMFN to highlight Canadian best practices in forest management in support of our environmental reputation will be explored. (ii) The CFS is currently assessing the strategic drivers for the Land Reclamation Project as it relates to FESA and Canada’s boreal zone. The CFS has also initiated work within the broader context of NRCan with external stakeholders to identify data and knowledge gaps related to Land Reclamation. As a key priority for the GoC and NRCan, CFS will evaluate and re-focus the investment in the Project commensurate with federal priorities, as part of its on-going resource allocation exercise. |

ADM/CFS March 2015 |

| Recommendation 2: Given the partial integration of the Biodiversity project area into the Ecosystem Integrity project area, it is recommended that NRCan further examine any risks associated with the reallocation and/or reduction of biodiversity expertise for CFS and the federal government. | Agreed. Actions to address the recommendation: (i) Within the context of the new Ecosystem Integrity Project, CFS will undertake a risk assessment to determine if the integration of the Biodiversity activities into the Project would compromise its ability to provide expertise on biodiversity to CFS and GoC. |

ADM/CFS March 2015 |

| Recommendation 3: Given the evolution of CFS science towards meeting federal policy priorities, it is recommended that NRCan clearly communicate its current and longer term plans to provinces (and other key users) by specifying what changes in expertise and outputs traditional users can expect. CFS should also consider enhancing dialogue between FESA scientists and CFS/NRCan policy staff to help clarify communication plans for traditional and new users. | Agreed. Actions to address the recommendation: (i) CFS has shared with Provinces and all staff its Strategic Framework that aligns science effort with policy needs to support federal priorities. (ii) In addition, CFS will continue to communicate with provinces and other stakeholders regarding our science outputs through the large number of boards and committees on which it sits. The active participation of scientists and policy analysts to FESA activities has been identified to strengthen the communication and understanding of the policy needs of NRCan/CFS. (iii) The CFS will ensure that the science-policy integration approach supports the NRCan strategic outcomes and its sector risk profile (that is updated at least annually). Thus, CFS will revise its strategic plan for the FESA starting in FY 2014-2015 to reflect its commitment in this regard. |

ADM/CFS March 2015 |

| Recommendation 4: Within the context of limited resources, it is recommended that NRCan enhance opportunities for its scientists to interact more frequently with target audiences, to ensure the effectiveness of the Sub-Activity and enable FESA to secure more external resources (financial and in-kind). | Agreed. Actions to address the recommendation: (i) Through its scientists, CFS will continue to emphasize knowledge exchange activities at the level of regional, national and international fora without compromising the TBS Travel Directive. (ii) CFS will explore and use innovative communication tools (webinars, web-surveys etc.) and capitalize on its strong partnerships to communicate CFS science to target audiences. |

ADM/CFS March 2015 |

| Recommendation 5: Within the context of limited resources, it is recommended that NRCan enhance the public dissemination of the science produced by the Sub-Activity. | Agreed. Actions to address the recommendation: i) CFS will undertake outreach and communication activities to disseminate scientific information on FESA science by: a) highlighting Canadian science for forest stewardship and forest sustainability by using science communications aimed at the public; and b) Incorporating knowledge exchange and other communication activities into the planning of FESA science projects. |

ADM/CFS March 2015 |

| Recommendation 6: It is recommended that NRCan continue to improve the tracking and reporting of performance and financial data to ensure that reliable information is used to manage its activities. | Agreed. CFS will take the following measures in this regard: (1) The CFS is currently working towards refining performance indicators for tracking our science performance and for linking these to our investments. This will also help clarify the targeted end-users. (2) A continual improvement in reporting information on finances, activities, outputs and outcomes will be available for subsequent years where any NRCan financial systems will enable tracking of resources for FESA activities and this expenditure information will be available shortly after FY-end. |

ADM/CFS March 2015 |

1.0 Introduction

This report presents the findings, conclusions and recommendations for the evaluation of Forest Ecosystems Science and Application (FESA) Program Sub-Activity.

The FESA Program Sub-Activity was established with the objective to increase scientific knowledge on forest ecosystems and support stakeholders in their sustainable forest management (SFM) policies and practices. This Program Sub-Activity is responsible for conducting research, national assessments and monitoring to develop, synthesize and integrate scientific knowledge. At the time of the evaluation, the FESA activities represented sub-activity 2.2.2 in the NRCan Program Activity Architecture (PAA) under Strategic Outcome #2, Environmental Responsibility.

The evaluation examined the issues of relevance and performance and covered the period from fiscal year 2007-08 to 2011-12. It included all six project areas under the FESA Sub-Activity with the exception of the African Model Forest Initiative (within the IMFN project area) that will be evaluated separately. The evaluation was conducted between November 2012 and August 2013 in accordance with the 2009 Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation and the Departmental Strategic Evaluation Plan (2012-13 to 2016-17).

The evaluation design and findings were informed by feedback from an Evaluation Advisory Committee (EAC) composed of management representatives from each project area of the Sub-Activity. Multiple lines of evidence were integrated, resulting in preliminary findings which were then presented to the Evaluation Advisory Committee (EAC) for validation.

2.0 Program Background and Profile

2.1 Context

Canada has almost 400 million hectares of forest, wooded or tree-covered land, representing about 10% of the world’s forest cover and 30% of the world’s boreal forest. Forests are important to the Canadian economy, with forest-related industries contributing about 1.9% to Canada’s gross domestic product in 2011Footnote 1 , as well as 222,000 direct jobs.Footnote 2

In addition to these direct economic values, forests worldwide are recognized as being important locations for biodiversity as well as serving ecological functions, such as regulating the hydrological cycle, protecting watersheds and storing genetic information.Footnote 3 There are new demands from both the Canadian public and environmental organizations for recognition of the entire range of environmental goods and services that forests supply beyond resource extraction.Footnote 4 At the same time, international environmental organizations are questioning the health of Canada’s forest ecosystems and the Canadian commitment to environmental stewardship.Footnote 5 In addition, studies on Canadian forests forecast significant changes in forest ecosystems over the coming decades, due to climate change.Footnote 6

The impacts of climate-induced changes, natural influences (i.e., disease), forest harvesting and land-use changes point to a need to monitor and assess the health of Canada’s forest ecosystems to support their sustainable development.Footnote 7 The FESA Program Sub-Activity is designed to produce scientific knowledge of Canada’s forest ecosystems that the public, government, industry and environmental organizations need for the responsible forest stewardship.Footnote 8

2.2 Mandate and Stakeholders

The objective of the FESA Program Sub-Activity is to increase scientific knowledge on forest ecosystems and support stakeholders in their SFM policies and practices. As part of this Program Sub-Activity, NRCan conducts research, national assessments and monitoring to develop, synthesize and integrate scientific knowledge. This knowledge is used by the appropriate government jurisdictions, industry, and other stakeholders to develop forest management practices and policies, and by NRCan and other federal government departments, to meet international reporting obligations, from Canada’s negotiating positions on international environmental issues related to forests, and counter misconceptions of Canada’s forest practices.Footnote 9 This work is conducted by the Canadian Forest Service (CFS) within NRCan. While it is important for CFS to produce scientific outputs that meet their stakeholders’ needs, the organization has recently made a shift towards better science-policy integration, in order to ensure that research is aligned with federal policy priorities in the area of forest ecosystems.

Activities of the FESA Program Sub-Activity are primarily in the following areas:Footnote 10

- Developing and maintaining national information on Canada’s forest ecosystems: to assess the state of the ecosystems and the indicators of ecosystem health, to assist in meeting Canada’s international reporting obligations, and to strengthen the understanding of Canada’s forest resource development standards and practices.

- Understanding ecosystem function and how it is impacted by resource development: to delineate risks to forest ecosystems posed by natural resource development and other anthropogenic or natural processes.

- Providing improved tools and practices needed to strengthen the integration of responsible environmental stewardship and forest resource development: to mitigate the anthropogenic risks.

- Exchanging knowledge and best practices domestically and internationally: to promote the responsible development of forest resources in Canada and globally.

As of 2011-12, this Program Sub-Activity consisted of the following six project areas. Note that Forest Biodiversity and Productivity & Dynamics merged into one project area, Ecosystems Integrity, in 2012-13 which is outside the evaluation reference period.

- Forest Biodiversity (Biodiversity), to determine the impacts of forest resource development and natural processes on biodiversity and develop a landscape-level risk management framework to aid in prioritizing NRCan-CFS forest research. A modest level of effort is focused on the impacts of forest management on the habitats of endangered species (e.g., woodland caribou) which are sometimes characterized as indicator species of biodiversity.

- Forest Carbon Research, Reporting and Policy Advice (Carbon) assesses forest-related carbon stock changes and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as an input into Canada’s reporting on GHG emissions – including to meet its annual obligations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and (formerly) under the Kyoto Protocol. In addition, it supports integration of forest carbon and GHG considerations into federal policy development and in improved forest management by providing science- and economics-based assessments of how forests can contribute to climate change mitigation. In support of this integration, it also transfers carbon modeling tools to stakeholders.

- Assessing and Understanding Ecosystem Productivity and Dynamics in Support of Sustainable Forest Management (Productivity & Dynamics), to assess the impacts of forest resource development on productivity, paying attention to the multiple factors at various scales in time and space (e.g., global environmental change, forest practices, wildfires, pests and other agents of tree mortality). This work aims to ensure that forest ecosystems remain resilient and productive. This work also improves the understanding of complex ecosystem dynamics related to forest productivity.

- Global Leadership in Development of the International Model Forest Network (IMFN), intended to be used as a platform to share Canadian best practices, knowledge of, and tools to promote responsible forest development globally; and to import knowledge and experiences gained elsewhere to aid in developing solutions to forest management challenges in Canada.

- National Forest Information and Assessment (Forest Assessment or NFIA) delivers an annual report to Parliament on the state of Canada’s forests (i.e., the annual State of the Forests Report), supports Canada’s reporting obligations under international agreements, and helps support market access issues. This work contributes to the development of products that provide information and advice on national forests (e.g., the National Forest Inventory) as well as contributing to the broader integration of systems for monitoring activities and research across disciplines.

- Land Reclamation research on reclaiming mined oil sands sites so that healthy, productive forests are restored. This also considers other ecosystem restoration activities over the longer term.

Key stakeholders for the six FESA areas are outlined in Table 1. Some of these stakeholders are considered to be clients, partners or users; however, roles may overlap (e.g., a client or partner could also be an information user).

| Stakeholders | Project areas | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-diversity | Carbon | Productivity & Dynamics | IMFN | Forest assessment | Land Reclamation | |

| Other CFS/NRCan programs | • | • | •4 | • | ||

| Other federal departments | •1 | •2 | • | •5 | •7 | •8 |

| Provinces/territories | • | •3 | • | • | •9 | |

| Hydro organizations | • | |||||

| Universities | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Forest industry and practitioners | • | • | • | • | ||

| External funding partners | •6 | |||||

| International organizations | • | • | ||||

| Non-governmental organizations | • | • | • | |||

| Canadian public | • | |||||

| Oil industry | • | |||||

| Oil-related associations | • | |||||

Notes: 1 - EC, DFAIT; 2 - EC, AAFC; 3 – via the National Forest Sinks Committee, which engages in policy-related analysis and facilitates provision of data needed by CFS to meet Canada’s forest carbon and GHG reporting commitments; 4 – the 60 sites on the network; 5 – CIDA, DFAIT; 6 – governments of other countries; 7 – CSA, AAFC; 8 – DFO, EC; 9 – primarily Alberta.

Source: Adapted from the Evaluation Assessment Report prepared by NRCan’s Strategic Evaluation Division (SED), citing NRCan ProMIS 2011-12.

2.3 Governance and Administration

The FESA Program Sub-Activity operates under the authority of the Natural Resources Act (1994) and the Forestry Act (1985). As per the former, the Minister shall, “seek to enhance the responsible development and use of Canada’s natural resources and the competitiveness of Canada’s natural resource products”.Footnote 11 Furthermore, as a result of the 2010 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy, the Minister of Natural Resources is responsible for, “advancing knowledge and communication” specifically by generating and disseminating “scientific knowledge related to forest ecosystems”.Footnote 12

The FESA Program Sub-Activity project areas report through the Assistant Deputy Minister of NRCan’s Canadian Forest Service (CFS). Each of the project areas within the Program Sub-Activity has a project coordinator. With the exception of the International Model Forest Network, each project coordinator is supported by peer directors such that the team responsible for a project area consists of a member from headquarters and members of regional research centres across CanadaFootnote 13 . The project coordinators report through two Directors General (DG Laurentian Forestry Centre and DG Northern Forestry Centre), who act as co-leads for this Program Sub-Activity.

2.4 Activities, Delivery and Organization

The FESA Program Sub-Activity encompasses a regional delivery model, with work carried out in the National Capital Region, as well as in five forestry research centres:

- Atlantic Forestry Centre (New Brunswick and Newfoundland)

- Great Lakes Forestry Centre (Ontario)

- Laurentian Forestry Centre (Quebec)

- Northern Forestry Centre (Alberta)

- Pacific Forestry Centre (British Columbia)

The six project areas of the FESA Program Sub-Activity differ in their objectives, activities and outputs, number of components, stakeholders, etc. This section presents a brief description of the primary activities, and expected outputs for each.Footnote 14

2.4.1 Forest Biodiversity

Description

The Forest Biodiversity (Biodiversity) project area operated from 2007-08 through 2011-12. The objective of this project area was to conduct nationally-relevant forest biodiversity science to support the provision of knowledge and advice to the forest sector that would strengthen Canada’s ability to demonstrate to markets the science-based foundation of Canada’s forest policy.Footnote 15 The context for this project area was the recognition that the pressures on the forest sector’s environmental reputation are largely related to biodiversity.Footnote 16

Activities and Outputs

Four primary activities were identified and aligned with five principal outputs as outlined in Table 2.

| Activities | Outputs |

|---|---|

|

|

2.4.2 Forest Carbon Research, Reporting and Policy Advice

Description

Since 2007-08, the Forest Carbon Research, Reporting and Policy Advice (Carbon) project area has developed scientific knowledge, models, reports and policy advice to inform/influence decision-making on the management of forest-related carbon and greenhouse gas emissions.Footnote 17

The objectives of this project area are to:Footnote 18

- enhance and integrate scientific knowledge about the determinants of forest carbon and greenhouse gas dynamics across various scales and the impacts of management;

- maintain and develop the National Forest Carbon Monitoring, Accounting and Reporting System to support policy and annual national/international reporting, including under the UNFCCC; and

- support the integration of forest carbon and greenhouse gas considerations in improved forest management by providing science- and economics-based assessment of how forests can contribute to climate change mitigation, and by transferring forest carbon/greenhouse gas information and assessment tools to stakeholders.

Activities and Outputs

Three primary activities and four outputs expected for the project are presented in Table 3.

| Activities | Outputs |

|---|---|

|

|

2.4.3 Assessing and Understanding Ecosystem Productivity and Dynamics in Support of Sustainable Forest Management

Description

The Assessing and Understanding Ecosystem Productivity and Dynamics in Support of Sustainable Forest Management (Productivity & Dynamics) project area existed from 2007-08 through 2011-12. It was intended to generate and integrate scientific knowledge, models and decision-support tools and policy advice for decision makers as well as to maintain market access.Footnote 19 Areas of focus were: understanding the impact of forest practices and climate change on ecosystem function; tracking and reporting on trends in Canada’s forest productivity, and providing baseline information for decision making regarding climate change mitigation.Footnote 20

The objectives of this project area were to:Footnote 21

- understand ecosystem functions and how they are impacted by forest practices and global change;

- track and report on the trends in Canada’s forest productivity over time; and

- provide baseline information for sound decision making, notably for climate change mitigation.

Activities and Outputs

Three primary activities and four outputs expected for the project area are presented in Table 4.

|

Activities |

Outputs |

|---|---|

|

|

2.4.4 Global Leadership in the Development of the International Model Forest Network (IMFN)

Description

The Global Leadership in the Development of the International Model Forest Network (IMFN) project area is a global community of practice in which members work towards the sustainable management of forest landscapes that has existed since 1992.Footnote 22 At the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro, the Government of Canada announced that it would “be the international counterpart to Canada’s domestic model forest program”.Footnote 23 The purpose of this was to “stimulate the field-level application of new concepts and ideas in SFM in forest ecosystems throughout the world and to create opportunities to demonstrate and share these experiences”.Footnote 24

Within this project area, there are essentially 5 components:Footnote 25

- Model Forests: defined as a geographic area and a specific approach to SFM. They are large-scale, long-term experiments for managing forested landscapes in a manner that adheres to six common principles while promoting and improving ecological, economic, and social sustainability. The six common principles are: broad, inclusive partnerships; landscape scale; commitment to sustainability; transparent, accountable governance; program of activities reflective of partner values and interests; and knowledge sharing, capacity building and networking.

- International Model Forest Network: as of March 20012 the IMFN consisted of over 60 model forests (14 Canadian, and 45 either established or under development outside of Canada) and had three main objectives: (1) to foster international cooperation and exchange of ideas relating to the working concept of SFM; (2) to support international cooperation in critical aspects of forest science and social science that underlie the search for new models of forest management; and (3) to support ongoing international discussions on the criteria and principles of sustainable development.

- IMFN Secretariat: currently housed within NRCan CFSFootnote 26 and is responsible for the implementation of the IMFN program. Its role is to facilitate the development of a network of model forests that is dedicated to managing the world’s forest-based landscapes in a sustainable manner. Specifically, the IMFN Secretariat provides centralized coordination of day-to-day support and development services to the Network, works to strengthen and expand the Network, and supports new and existing model forests when there is no regional network support in place at the site-level.

- Regional Model Forest Networks: through the IMFN, Secretariat regional networks have been established in Latin America, Africa, Europe, Asia and the Mediterranean to more effectively define, articulate and manage a regional program of SFM. The Canadian Model Forest Network is a member of the IMFN and is treated as a regional network of the IMFN. These regional networks reflect the unique priorities, strengths and opportunities in that specific region. They also facilitate regional communication and knowledge exchange, capacity building and funding opportunities for existing and potential model forests. The network is therefore very non-hierarchical, with significant autonomy and responsibility vested in regions with the overall effort functioning in a voluntary (non-legally binding) manner.

- Model Forests in Africa: as of July 2008, there were two model forests in Africa (both in Cameroon), the development of which were started by the IMFN Secretariat in 2003. In March 2008, North Africa, Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia indicated an interest in joining a regional network and the IMFN. By the end of 2012, a total of 8 Model Forests were in various stages of development in Africa. These Model Forests are supported by local authorities within each country’s government and by a national coordinator for the African Model Forest Network.Footnote 27 The objective of the African Model Forest Initiative (AMFI) is to “improve the conservation and sustainable management of forest resources in the Congo Basin and the Mediterranean regions of Africa”. The Africa Model Forest Network is unique within the IMFN, having been funded largely through a $15 million contribution from Canada.

Activities and Outputs

Three primary activities and four outputs expected for the project area are presented in Table 5.

| Activities | Outputs |

|---|---|

|

|

2.4.5 National Forest Information and Assessment (NFIA)

Description

The National Forest Information and Assessment (Forest Assessment or NFIA) project area has existed since 2007-08 to provide fundamental information on the forest resources and ecosystems.Footnote 29 This information is required for Canada to meet its science, policy, program and reporting commitments.Footnote 30

The objectives of this project area are to:Footnote 31

- track changes in Canada’s forest resources, conduct analysis and forecasting that will support decision-making related to policy, investment and trade; and

- provide information to support regional, national and international business objectives and science initiatives of CFS.

Activities and Outputs

Three primary activities and four outputs expected for the project area are presented in Table 6.

| Activities | Outputs |

|---|---|

|

|

2.4.6 Reclamation of Disturbed Forest Landscapes

Description

The development of oil sands in Alberta has had significant environmental impacts on forested landscapes and watersheds.Footnote 32 The Reclamation of Disturbed Forest Landscapes (Land Reclamation) project area was created in 2011-12 to conduct research on reclaiming mined oil sands sites to enable the restoration of healthy, productive forests. This research is being conducted in collaboration with NRCan’s Innovation and Energy Technology Sector.Footnote 33

The objectives of this project area are to:Footnote 34

- assess the current state of knowledge on reclamation practices designed to ensure that re-established ecosystems provide essential ecosystem goods and services;

- identify knowledge gaps;

- generate knowledge to support effective mitigation and reclamation practices; and

- develop tools to enable policy and decision-making.

Activities and Outputs

Two primary activities and five outputs expected for the project area are presented in Table 7.

| Activities | Outputs |

|---|---|

|

|

2.4.7 Distribution of components by project area

Considering these activities and outputs, the six FESA Program Sub-Activity project areas supported a total of 502 components between 2007-08 and 2011-12 (see Table 8).Footnote 36 A component can be any type of activity that contributes to the overall intended outcome. Examples of common components include scientific research studies, working groups, development of tools or new networks, mapping activities, knowledge translation, development of online services and more.

Table 8 indicates an overall decrease in the number of components across all projects areas since 2008-09 (except for Land Reclamation, since it was launched in 2011-12). This reduction occurred as a result of ongoing efforts from program management to refocus and streamline projects by ensuring that similar work conducted across CFS centres was grouped into one component, rather than having individual components for each centre. The intent of this exercise was to increase coordination, efficiency and collaboration across CFS centres.

Forest Biodiversity has the highest number of components, with almost a third of the total number. On the other hand, IMFN and Land Reclamation have fewer components when compared to the other project areas (47 and 6 components, respectively).

| Fiscal Year | Biodiversity | Carbon | Productivity & Dynamics | IMFN | NFIA | Land Reclamation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007-08 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2008-09 | 41 | 36 | 30 | - | 38 | - |

| 2009-10 | 30 | 29 | 34 | 10 | 22 | - |

| 2010-11 | 39 | 30 | 21 | 8 | 18 | - |

| 2011-12 | 18 | 16 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Total | 128 | 111 | 93 | 25† | 85 | 6 |

Note: † The three AMFI components (one per year) are included in the total; however these components were not examined as part of this evaluation.

Source: NRCan. ProMIS

2.5 Funding and Resources

Table 9 presents the total resources for the FESA Program Sub-Activity per project area during the evaluation period (2007-08 to 2011-12), including actual internal expenditures (A-base and C-base) and external support (actual financial and planned in-kind). As part of C-base funding, the Sub-Activity received funding for forest policy, monitoring and capacity-building activities as part of horizontal initiatives funded by the Government of Canada. These include, the Mackenzie Gas Project, Clean Air Agenda, and International Polar Year.

| Project area | Internal resources (actual) | External resources | TOTAL (actual + planned in-kind) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-base | C-base | Internal TOTAL* | Financial (actual) | In-kind (planned)** | ||

| Biodiversity | 16.6 | 1.0 | 17.7 | 0.5 | 2.9 | 21.1 |

| Carbon | 12.3 | 6.8 | 19.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 19.8 |

| IMFN*** | 1.9 | 4.4 | 6.4 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 7.7 |

| NFIA | 21.8 | 1.2 | 23.1 | 3.2 | 6.3 | 32.6 |

| Productivity & Dynamics | 16.8 | 0.4 | 17.2 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 19.3 |

| Land Reclamation | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.1 |

| TOTAL | 70.3 | 14.1 | 84.4 | 5.7 | 11.4 | 101.5 |

Notes: Totals may be ±0.1 due to rounding.

* Internal (NRCan) funding includes A-base and C-base, and covers salary, operating and maintenance, G&Cs and transfer payments.

** Data on in-kind contributions are not available for 2007-08.

*** Figures exclude G&C funding for the African Model Forest Initiative because the AMFI is part of a separate evaluation. The IMFN became part of the FESA Program Sub-Activity in 2009-10 and these figures do not include prior funding.

† The land reclamation project area started in 2011-12.

Source: Compiled by NRCan. Internal and external resources, Actual Expenditures Reported by FESA; In-kind contributions, ProMIS.

Table 10 presents the expenditures by type – Operating and Maintenance (O&M), Salary, and Grants and Contributions (G&C) – for the FESA Program Sub-Activity by project area during the evaluation period (2007-08 to 2011-12). Note that this table does not include the in-kind resources presented in Table 10, such that the total is reduced by $11.4 million, from $101.5 to $90.1 million.

| Expenditure type | Biodiversity | Carbon | IMFN | NFIA | Productivity & Dynamics | Land Reclamation | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O&M | 2.5 | 3.2 | 2.0 | 7.9 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 18.1 |

| Salary | 15.7 | 16.2 | 2.1 | 18.4 | 15.6 | 0.8 | 68.9 |

| G&C | 0 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.1 |

| Total | 18.2 | 19.4 | 7.2 | 26.3 | 18.0 | 1.0 | 90.1 |

Note: Both O&M and Salary expenditures include A-base, C-base and External; exclude in-kind

Source: Forest Ecosystems IO

2.6 FESA Logic Model

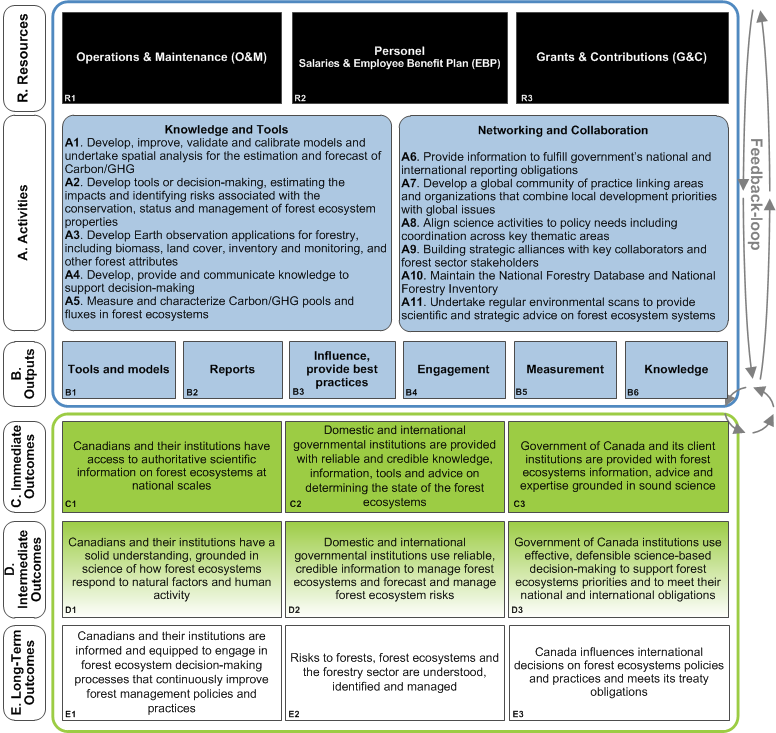

The Program Sub-Activity-level logic model that outlines the program theory is presented in Figure 1. This logic model was developed by the FESA Program Sub-Activity (also referred to internally as the Forest Ecosystems Intended Outcomes), and adapted for the evaluation.

The first row of the logic model identifies the main types of financial resources (inputs) that support the activities, outputs and outcomes of the FESA Program Sub-Activity outlined in the following rows.

Figure 1 FESA Program Sub-Activity Logic Model

Source: Adapted from NRCan. (2012). Evaluation Assessment Report of FESA Program Sub-Activity

Text version

Figure 1 FESA Program Sub-Activity Logic Model

| Logic Model Components | Descriptions of Each Component | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. Resources |

R1. Operations & Maintenance (O&M) R2. Personnel, Salaries & Employee Benefit Plan (EBP) R3. Grants & Contributions (G&C) |

|||

| A. Activities |

Knowledge and Tools A1. Develop, improve, validate and calibrate models and undertake spatial analysis for the estimation and forecast of Carbon/GHG A2. Develop tools or decision-making, estimating the impacts and identifying risks associated with the conservation, status and management of forest ecosystem properties A3. Develop Earth observation applications for forestry, including biomass, land cover, inventory and monitoring, and other forest attributes A4. Develop, provide and communicate knowledge to support decision-making A5. Measure and characterize Carbon/GHG pools and fluxes in forest ecosystems |

Networking and Collaboration A6. Provide information to fulfill government’s national and international reporting obligations A7. Develop a global community of practice linking areas and organizations that combine local development priorities with global issues A8. Align science activities to policy needs including coordination across key thematic areas A9. Building strategic alliances with key collaborators and forest sector stakeholders A10. Maintain the National Forestry Database and National Forestry Inventory A11. Undertake regular environmental scans to provide scientific and strategic advice on forest ecosystem systems |

||

| B. Outputs |

B1. Tools and models B2. Reports B3. Influence, provide best practices |

B4. Engagement B5. Measurement B6. Knowledge |

||

| C. Immediate Outcomes |

C1 Canadians and their institutions have access to authoritative scientific information on forest ecosystems at national scales |

C2 Domestic and international governmental institutions are provided with reliable and credible knowledge, information, tools and advice on determining the state of the forest ecosystems |

C3 Government of Canada and its client institutions are provided with forest ecosystems information, advice and expertise grounded in sound science |

|

| D. Intermediate Outcomes |

D1 Canadians and their institutions have a solid understanding grounded in science of how forest ecosystems respond to natural factors and human activity |

D2 Domestic and international governmental institutions use reliable, credible information to manage forest ecosystems and forecast and manage forest ecosystem risks |

D3 Government of Canada institutions use effective, defensible science-based decision-making to support forest ecosystems priorities and to meet their national and international obligations |

|

| E. Long-term Outcomes |

E1 Canadians and their institutions are informed and equipped to engage in forest ecosystem decision-making processes that continuously improve forest management policies and practices |

E2 Risks to forests, forest ecosystems and the forestry sector are understood, identified and managed |

E3 Canada influences international decisions on forest ecosystems policies and practices and meets its treaty obligations |

|

Source: Adapted from NRCan. (2012). Evaluation Assessment Report of FESA Program Sub-Activity

3.0 Evaluation Objectives, Scope, and Methodology

3.1 Objectives and Scope

This evaluation was mandated by NRCan’s Evaluation committee in accordance with the Financial Administration Act and the 2009 Treasury Board Policy on EvaluationFootnote 37. The primary objective of the evaluation was to assess issues relating to the relevance and performance of the FESA Program Sub-Activity and provide recommendations as necessary for the period from 2007-08 to 2011-12.

All six project areas were covered by the evaluation, with the exception of the African Model Forest Initiative (within the IMFN project area). The evaluation followed a theory-based approach,Footnote 38 in which emphasis is placed on the process by which the program arrives at its expected results (see further details in the next section).

This evaluation addresses the five core evaluation issues defined by the Treasury Board Secretariat in the Directive on the Evaluation Function, effective April 2009:

Relevance of the FESA Program Sub-Activity:

- Continued need for Program (R1)

- Alignment with government priorities (R2)

- Alignment with federal roles and responsibilities (R3)

Performance (effectiveness, efficiency and economy) of the FESA Program Sub-Activity:

- Achievement of expected outcomes (P1 & P2)

- Demonstration of efficiency and economy (P3 & P4)

These five evaluation issues are addressed through a series of specific evaluation questions, which are answered in Section 4.0.

3.2 Methods

The evaluation questions and the selection of methods were informed using a theory-based approach and were developed in consultation with the Evaluation Advisory Committee. A theory-based approach was recommended by the evaluation assessment to structure and undertake the analysis in this evaluation as an alternative to an experimental design evaluation. While an experimental design typically measures both the baseline and the final results associated with an intervention by incorporating comparison groups, “theory-based approaches to evaluation use an explicit theory of change to draw conclusions about whether and how an intervention contributed to observed results”.Footnote 39

Accordingly, this evaluation placed more emphasis on the process by which the program arrives at its expected results using a theory of change to help track the linkages and contribution of outputs to outcomes and to tell the story of performance. A theory-based approach to evaluation is particularly useful for the assessment of a Sub-Activity being evaluated for the first time as it helps understand why and how the observed results occurred in various contexts. Using this conceptual analytical model, the evaluation was designed to draw on various sources of data to ensure that the combined lines of evidence resulted in an in-depth and comprehensive analysis. A data collection matrix was used to cross-link evaluation questions with associated performance indicators, data collection methods and data sources, allowing data to be triangulated.

Five methods were used to collect and analyze evidence. Table 11 presents details on each data collection method.

| Data Collection Method | Details |

|---|---|

| 1. Document, file and data review | A review of approximately 200 documents, secondary literature, files and Sub-Activity data including:

|

| 2. Database review | A review of CFS ProMIS planning database conducted by NRCan-SED |

| 3. Stakeholder interviews and focus groups | Total number of interviews.................................................................... 97

|

| 4. Survey | Online survey of project area component leads

|

| 5. Bibliometrics and webmetrics | Bibliometric analysis

|

Note: † Valid response rate = Number of completed surveys, divided by the valid sample, which excludes unreachable potential respondents; ‡ Calculated for a response distribution of 50% (i.e., 50% yes/50% no); 95% confidence level (19 times out of 20)

3.3 Evaluation Challenges, Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

The challenges and data limitations encountered during this evaluation, and the mitigation strategies adopted to counter them, are discussed below. Generally, challenges were anticipated early in the process and associated mitigation strategies were proactively built into the evaluation design. A key mitigation strategy used was the comparison of information obtained from different data collection methods to validate findings.

3.3.1 Challenges

Broad scope of the sub-activity: The broad scope of FESA components, spread across six different project areas meant that a large range of different stakeholder groups had to be consulted, both within and outside the federal government. While this presented some difficulties in discerning the commonalties within groups, this issue was mitigated to a large extent through the use of qualitative data analysis software.

Multiple/diverse roles of internal stakeholders: Some interviewees and focus group participants representing NRCan (but outside the FESA) were sometimes both users and producers of FESA information, which posed challenges to mapping of outputs/outcomes and feedback within FESA overall and for specific project areas. To mitigate potential for bias, interviewees/focus group participants were asked to differentiate when speaking from a user vs. a producer perspective.

Awareness of sub-activity: Some external stakeholders had difficulties differentiating FESA activities from other CFS activities even though mitigation strategies were implemented such as using specific prompts.

Evaluation design: The granularity of the information required in the data collection matrix did not allow for distinct coverage of all questions and indicators. As a result, interview questions were combined in these cases and some questions were not covered in all interviews.

In addition, the distinction between some intermediate and ultimate program outcomes was found to be conceptual rather than operational. As a result, some answers to some interview questions were combined. This was the case particularly for performance questions.

Fieldwork challenges: During the fieldwork phase it was challenging to schedule nearly 100 interviews (and five focus groups across Canada) and analyze data collected through this method within a short timeline.

3.3.2 Data limitations

Data gaps: An apparent data gap arose on the issue of forest ecosystem risk. Two reasons may explain this gap: 1) indicators for these two questions were not as comprehensively covered in the interview/focus group guides and 2) interviewees tended to focus on the contribution of FESA to their everyday activities rather than on identification/ understanding/management of risks.

In addition to this general data gap, there are also data limitations associated with each data collection method:

Survey: The survey was only administered to internal stakeholders, in particular representatives of individual project areas that produce FESA outputs. To mitigate, the evaluation extensively consulted external stakeholders via the interview and focus group methods. Cautious interpretation of survey results should also be exercised given the survey’s relatively high margin of error (8.3%).Footnote 40

Document review: The availability, quality and comprehensiveness of documents across project areas were highly uneven. Particularly, the evaluation team was faced with a lack of performance measurement data such as quarterly or annual progress reports or limited evidence of the implementation of a performance measurement strategy. To the extent possible, performance measurement information was collected through interviews and the survey.

Bibliometric analysis: The bibliometric framework used for this evaluation does not aim to be a complete inventory of FESA’s output. The keyword-based searches may not capture all relevant documents. In addition, the method also has some inherent limitations such as that the bibliometric databases tend to have a slight bias for countries that publish in English-language journals. Although French was included in the analysis, it is possible that other countries may be underestimated. Lastly, different citation patterns may be observed across disciplines, which may complicate their comparison.

Database review: The CFS ProMIS is a planning database and as such does not include any reporting on outcomes and financials. As a result, actual expenditures were reported separately by FESA. Relevant information from the two datasets needed to be manually combined into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet in order to enable the analysis of data.

4.0 Evaluation Findings

4.1 Relevance

4.1.1 Continued Need for the Program (Issue 1)

Question 1: Is there an ongoing need for the Program Sub-Activity?

FESA remains highly relevant to address several environmental and economic needs, such as compiling and reporting national information on the state of Canada’s forests, providing expertise to address the impact of climate change and facilitating market access for Canadian forest products. FESA’s specialized and long-standing scientific expertise inevitably fills a gap, addressing topics not covered by academia, provincial governments or other organizations.

Specific ongoing needs were also identified within individual FESA project areas. Notably, there is a need for CFS to clearly identify its niche within the Land Reclamation area considering the complexity of the topic and the many players already involved.

Identified needs: All lines of evidence confirmed that FESA remains highly relevant to address several ongoing environmental and economic needs. On the economic side, the forestry sector in Canada employs some 600,000 people (direct and indirect jobs), and supports approximately 200 Aboriginal and forest-based communities.Footnote 41 At the same time, the international market context for Canadian forest products has changed dramatically during the last decade. Market access is now strongly influenced and facilitated by Canada’s reputation as a global leader in sustainable forest management (SFM).Footnote 42 ,Footnote 43 To maintain this position, Canada must draw on balanced and credible scientific expertise to support policy direction and to enable participation in international forums on related issues.Footnote 44 While the FESA sub-activity does not involve direct market access activities, there is an ongoing need for the sub-activity as it directly supports and links to the overall NRCan objectives relating to the forest resource sector.

On the environmental side, a need to better understand climate change impacts and climate change mitigation potential, as well as to preserve national biodiversity, are supported through FESA activities, as outlined throughout the Performance section of this report. Furthermore, Canada’s forests are a large store of carbon and important in the global carbon cycleFootnote 45 – thus understanding how management activities and natural disturbances affect the carbon is particularly relevant in the context of addressing global climate change.Footnote 46

Unique expertise: Having identified these ongoing needs, FESA provides the unique and long-standing expertise in forest ecosystem science that is particularly relevant to address climate change mitigation and adaptation issues and to make decisions that support forestry sector competitiveness. Internal and external interviewees also widely referred to the need for scientific information that would help maintain or generate social acceptance of forest harvesting and management practices within and outside Canada to facilitate market access.

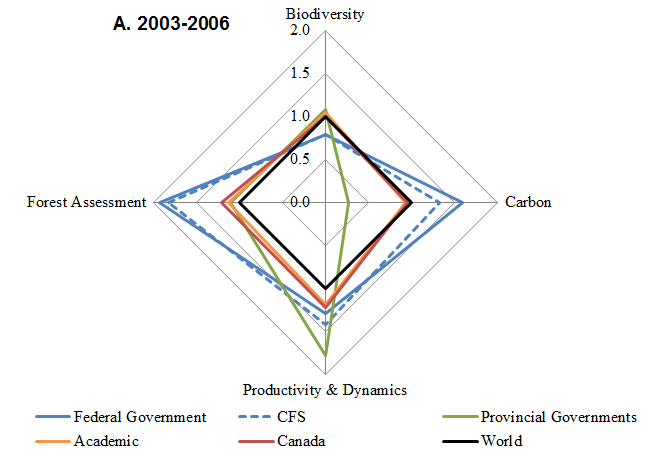

An analysis of the specialization pattern of Canadian sectors across FESA project areas further suggests that FESA provides unique scientific expertise in the Canadian forestry context. Indeed, compared to other Canadian sectors, the 2003-2006 and 2008-2011 analyses (see Figure 2) indicate that CFS and the federal government allocate a much greater share of their forestry output, relative to the world, in the Forest AssessmentFootnote 47 and CarbonFootnote 48 project areas. These findings show that the federal government and CFS (especially in recent years) have been filling a gap in areas that do not constitute the core activities, in relative terms, of academia and provincial governments.

Figure 2 Specialization(*) patterns of Canadian sectors within Forestry across FESA project areas, (A) 2003-2006 and (B) 2008-2011

Note: (*)The level of specialization or Specialization Index (SI), applied in the context of this evaluation, measures the share of scientific output of sectors (i.e. federal government, CFS, Academia, provincial governments) within four FESA project areas, relative to their total output in forestry and compared to the share at the world level. An index above one is indicative of a relative specialization, whereas an index below one is indicative of a lack of specialization.

Source: Computed by Science-Metrix using the WoS

Text version

Figure 2 Specialization(*) patterns of Canadian sectors within Forestry across FESA project areas, (A) 2003-2006 and (B) 2008-2011

Figure 2 depicts two graphs derived from a bibliometric analysis showing specialization patterns of scientific publications for Canadian sectors within forestry across FESA project areas: Forest Assessment, Biodiversity, Carbon, and Productivity and Dynamics. The figure depicts a comparison of scientific publications produced by the federal government, the Canadian Forest Service (CFS), academia, provincial governments and the world. The first graph (A) shows the specialization patterns for the years 2003 to 2006. The second graph (B) shows the specialization patterns for the years 2008 to 2011.

The two graphs show that the Federal Government and CFS exhibit similar specialization patterns which is not surprising considering that the CFS contributed to two thirds of the federal production in Forestry. However, their specialization patterns differ from that of academia and the provincial governments. Graphic A (2003-2006) indicates that whereas Canada and academia had a rather balanced specialization patterns with scores near or slightly above the world level in all areas and the provincial governments were strongly specialized in Productivity & Dynamics, slightly specialized in Forest Assessment, on a par with world level in Biodiversity and well below world level in Carbon, the Federal Government and CFS showed a strong specialization in Forest Assessment, moderate specialization in Productivity & Dynamics as well as in Carbon and were slightly below world level in Biodiversity.

In the second half of the study period (2008–2011) as depicted in Graphic B (2008-2011), Canada and academia remained well balanced with a slight increase in a specialization in the Carbon project area. A similar increase in Carbon was observed for both the provincial governments and CFS, although provincial government scientific output remained below world level. The provincial governments also increased their specialization in Forest Assessment getting closer to the specialization level of the federal government and CFS.

The federal Government (mostly CFS) remained the most specialized one in Forest Assessment and except for the Academic sector the only specialized one in Carbon. Finally, the observed increase in the specialization of the Federal Government and CFS in Biodiversity in 2008–2011 indicates a slight shift towards the only area in which Canada does not yet specialize (among the selected four project areas).

Biodiversity is the only area in which none of the sectors is specialized. In 2003-2006, nearly all sectors were devoting an equal share of their forestry output to Biodiversity as the world was (i.e., SI = 1), the only exception being CFS (and the federal government) with a smaller share than the world (SI < 1). In 2008-2011, the specialization of most sectors decreased very slightly. Only CFS (or the federal government) increased its specialization in Biodiversity approaching world level. This increase in specialization is attributable to a faster increase in the share of its forestry output (or that of the federal government) allocated to Biodiversity than observed at world level; it reached 23% in 2008-2011 compared to about 17% in 2003-2006. This is the strongest increase in the concentration of CFS (or the federal government’s) forestry output in a given area. Nevertheless, Biodiversity remains the only area in which Canada does not have a specialization above world level in 2008-2011; it even decreased slightly relative to 2003-2006.

Project areas: Ongoing needs specific to individual project areas were also identified in reviewed documentation and during interviews/focus groups. For instance, within the Forest Assessment project area there was wide consensus on the need to maintain and enhance the National Forest Inventory (NFI), a component which provides important scientific information to the Government of Canada. FESA’s role was deemed critical to integrate and harmonize data produced by provincial jurisdictions to provide an overarching, national picture of the state of Canada’s forests. Moreover, the NFI generates baseline information on forests that informs research activities carried out within all other FESA project areas. It also informs a number of other CFS activities to enhance Canada’s forest management practices.Footnote 49 The ability to provide credible information on sustainable forest management also influences Canada’s position in the competitive forest products market and thus relates to broader NRCan objectives as discussed above.Footnote 50

In the Carbon project area, FESA also plays a significant role, as it provides research and policy advice, the demand for which is expected to increase within the federal government. As an example, CFS recently contributed to Environment Canada’s report on GHG reduction potential, estimating reduction potential for different land use scenarios.Footnote 51 It is expected that Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry will have an increasing impact on global carbon accounting policies and practices,Footnote 52 an area for which CFS is responsible. In addition, following the termination of the Canadian Carbon Program in 2011, NRCan has indicated that CFS should play the lead role in coordinating further Canadian carbon science. Footnote 53

Similarly, the Land Reclamation project area is meant to fill significant research and policy gaps in this relatively new topic.Footnote 54 This project area focuses on the Alberta oil sands, a complex issue that requires CFS to adopt a highly collaborative approach within NRCan, the Government of Alberta and many other forest sector players that are already active in this field.Footnote 55 To avoid duplication of effort, CFS must clearly identify which research questions it can best address and allocate funding and human resources accordingly.

The project area entitled Ecosystem Integrity unified two existing project areas (Biodiversity and Productivity & Dynamics) in 2011-12 to better address policy needs. The new project area uses biodiversity expertise to focus on how forest management affects forest properties, through the development of ecosystem integrity indicators.Footnote 56 However, while this restructure helped clarify and focus the scope of research conducted within these two project areas, interviewees noted that some biodiversity scientists were excluded as their work was no longer aligned with the objectives of the new project area. On the other hand, the new project area was generally considered successful in ensuring strong science-policy integration, given the reasonably limited resources available.

These findings may indicate an ongoing need for sustained efforts to ensure that scientists (primarily in the regions) and the policy makers meet regularly and work collaboratively towards the fulfillment of policy priorities related to forest ecosystem research. This could be achieved by ensuring, at the beginning of each project, that scientists clearly articulate the expected impact of their work on policy.

Finally, evidence from the evaluation confirms that participation in the IMFN initiative is increasing worldwide, which demonstrates an ongoing need for the network. Membership has grown to 60 Model Forests in more than 30 countries. Footnote 57 Canadian Model Forests and IMFN have brought diverse stakeholder groups (e.g., industry, government, First Nations, community-based associations, ENGOs, educational and research institutions and private landowners) together to generate new ideas and on-the ground solutions to sustainable forest management issues.Footnote 58 Interviews with internal and external stakeholders confirmed that there is an ongoing important need for IMFN and that this project area currently adequately meets needs, given the current level of FESA resources. IMFN stakeholders suggested that given the wide regional experience of the various Model Forests, IMFN should consider exploring themes that could apply “globally” such as governance, integrated landscape management, climate change, building local capacity, etc. NRCan stakeholders note that IMFN itself is a governance model in the service of “integrated landscape management.” The network meets every three to four years to discuss global themes. In 2011, the network agreed upon the following global issues: Climate Change, Environmental Goods and Services, Community Sustainability, and Knowledge Management.

Moreover despite the fact that stakeholders believe there is a need for IMFN, this project area was ratedFootnote 59 a lesser priority than the other project areas by science and policy experts surveyed as part of a CFS 2011 Environmental Scan.Footnote 60 However, the report highlights that, despite priority ranking, “there was strong support for the activities that could be expected from a model forest: Work and training in the application of ecosystem-based forest management would significantly advance the understanding and application of this approach (58% of respondents); and Informal networks of forest areas piloting and demonstrating the application of ecosystem-based forest management would significantly advance the understanding and application of this approach (55% of respondents).”

4.1.2 Alignment with Government Priorities (Issue 2)

Question 2: Is the Program Sub-Activity consistent with government priorities and NRCan strategic outcomes?

FESA’s expected outcomes have been clearly aligned with federal priorities and NRCan’s strategic objectives throughout the evaluation period. Namely, these include the development of a competitive forest industry and responsible natural resource management. In terms of the six project areas, there is less direct alignment between IMFN and FESA. However, a scan of the NRCan PAA indicates that the IMFN contributes to – or could potentially be relevant for – other Sub-Activity Programs under the responsibility of CFS.

Federal priorities: The objectives of the FESA Sub-Activity overall, and the objectives of most individual project areas are highly aligned with the priorities of the federal government and the strategic objectives of NRCan. In fact, documentary evidence such as Budgets,Footnote 61 Speeches from the ThroneFootnote 62 and the Economic and Action PlanFootnote 63 suggests that GoC priorities have included development of a competitive forest industry for at least the last decade.

Departmental outcomes: FESA is also consistent with NRCan’s mandate to create a sustainable resource advantage within departmental Strategic Outcome # 2 “Natural Resource Sectors and Consumers are Environmentally Responsible”.Footnote 64 Under NRCan’s 2012-2013 Program Activity Architecture (PAA), FESA is aligned with PA 2.3 “Responsible Natural Resource Management, which seeks to ensure that “public and private sectors establish practices to mitigate the environmental impacts to natural resources”.

Among the six FESA project areas, there is less direct alignment between IMFN and FESA Sub-Activity. The Sub-Activity’s stakeholders consulted perceived that the domestic mandate of FESA does not clearly parallel the international goals of the IMFN. However, a scan of the NRCan PAA indicates that the IMFN contributes to – or could potentially be relevant for – other Sub-Activity Programs. In fact, as the IMFN is envisioned to lead in developing the international network “as a platform to import knowledge and experiences gained elsewhere to aid in developing various solutions to forest management challenges in CanadaFootnote 65 [65]”, the IMFN objective is relevant to more than one single Sub-Activity Program, including FESA and other Sub-Activity Programs under the responsibility of CFS, including (but not limited to):

- Positive perception of Canadian forest practices and products among targeted stakeholders in key international markets (Sub-Activity 1.1.2 : Forest Products Market Access and Development,Footnote 66 and;

- Forest-based and Aboriginal communities have the knowledge needed to take advantage of emerging economic opportunities: Sub-Activity 1.3.2: Forest-based Community Partnerships.Footnote 67

In addition, a recent independent studyFootnote 68 commissioned by NRCan to inform the decision-making process about the IMFN secretariat confirmed existing and potential links between the IMFN and the Government of Canada agenda. In its recommendations, the study highlights the value proposition of the IMFN to the GoC:

- “The most attractive value proposition of the IMFN to the GoC is based on the contribution of the network to Canada’s declared objective of sustainable prosperity from natural resource development. Model Forests can show how an important natural resource can be effectively managed in the context of multiple objectives –environmental, social and economic – at the same time contributing to the fulfillment of Canada’s international obligations with respect to climate change and sustainable natural resource development.”

4.1.3 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities (Issue 3)

Question 3: Is there a legitimate, appropriate and necessary role for the federal government in these project areas?

Although forests generally fall under provincial/territorial jurisdiction, the role of the federal government is legitimate to conduct forest ecosystem research and develop a national and long-term perspective supported by science-based information. The Government of Canada is also uniquely positioned to represent Canada’s interests globally and to address international obligations.

Furthermore, CFS’ output in forest ecosystem research, relative to provinces/territories and academia, suggests that it complements the roles of others and several examples of synergistic work were identified.

However, there is an opportunity to re-examine the role for CFS in the IMFN project area to better align with the FESA mandate, and to clarify its role in Biodiversity research. Considering the fact that the bibliometric analysis indicated that none of the other sectors (i.e., academic and provincial government sectors) are specialized in forest biodiversity research, the recent increase in specialization of CFS in Biodiversity research (the strongest increase in the concentration of CFS’ forestry output in a given project area), and the ongoing need for Biodiversity science to help support international commitments, it appears to be appropriate that the federal government maintain its role and expertise in this area. CFS plays an important role in supporting biodiversity relevant to forestry.

In the case of the IMFN, given that it is unlikely to find an external host (without substantial financing accompanying such a transfer) there is an opportunity for CFS to deliberately engage the department regarding opportunities for scientific research, knowledge mobilization on sustainable management of forest-based landscapes and for other relevant actionable issues.

To clearly manage provincial expectations and acknowledge long-standing relationships, there is a need for FESA to regularly communicate any changes in its expertise and services because of increasing focus on federal priorities.

Legitimate role: While more than 70% of Canada’s forests are administered by provinces and territories, the federal government remains responsible for areas under national jurisdiction, including economy, trade, international relations, science, technology and the environment.Footnote 69 FESA’s mandate relating to the production of scientific knowledge for sustainable forest management and the coordination of information at the national level is aligned with the above federal responsibilities. Therefore, it is legitimate for the federal government to be delivering FESA activities.