Evaluation of the Energy and Climate Change Policy (ECCP) Program

Audit and Evaluation Branch

Natural Resources Canada

December 18, 2020

Table of Contents

- List of acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Evaluation objectives and methods

- Evaluation limitations and mitigation strategies

- What we found: program design

- What we found: relevance

- What we found: program delivery

- Conclusions

- Appendix 1: Theory of change for the ECCP Program (Policy is not linear)

- Appendix 2: Survey methodology and limitations

- Appendix 3: List of key documents referenced in report

- Appendix 4: Evaluation team

List of acronyms

- ADM

- Assistant Deputy Minister

- AEB

- Audit and Evaluation Branch

- CCEI

- Canadian Centre for Energy Information

- ECCC

- Environment and Climate Change Canada

- ECCP

- Energy and Climate Change Policy

- ES

- Energy Sector

- EPB

- Energy Policy Branch

- EMMC

- Energy and Mines Ministers’ Conference

- GHG

- Greenhouse Gas

- LCES

- Low Carbon Energy Sector

- NRCan

- Natural Resources Canada

- PCF

- Pan-Canadian Framework (on Clean Growth and Climate Change)

- SPPIO

- Strategic Petroleum Policy and Investment Office

- TB

- Treasury Board (of Canada)

- UNFCCC

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

Executive Summary

About the Evaluation

This report presents the findings, conclusions, and recommendations from the evaluation of the Energy and Climate Change Policy (ECCP) Program. This Program provides policy advice to the Minister of Natural Resources, senior government officials, and other stakeholders to inform decision-making on matters related to energy and climate, including the future pathway for Canada’s energy sector. The evaluation covers the period from 2014-15 to 2018-19. Total program expenditures over this period were approximately $42 million.

Though the Energy Policy Branch has provided this policy function for a number of years, Energy and Climate Change Policy was not designated as a formal Program until the development of Natural Resources Canada’s (NRCan)’s new Departmental Results Framework. Since this time, the ECCP Program has continued to evolve. Given this, rather than focus on achievement of results, the objective of this formative evaluation was to examine the design and delivery of the ECCP Program.

The evaluation of policy functions is relatively uncommon and not well understood. The policy process is inherently complex and non-linear, making it hard to measure and evaluate. In 2018, NRCan’s Audit and Evaluation Branch worked in close collaboration with the Energy Policy Branch to develop an innovative, forward-looking evaluation approach.

The evaluation was completed in two steps:

- Confirm or revise the ECCP Program’s theory of change, i.e., its results logic, reach and the causal relationships between its activities, outputs and outcomes.

- Examine the recent design and delivery of the ECCP Program to assess the extent to which this enables it to respond to identified needs and achieve (or contribute to) its intended outcomes. This includes consideration of the internal and external factors that might hinder or facilitate the Program and (to the extent possible) the nature and magnitude of their impact.

The starting frame for this evaluation was the Program description and results logic included in the ECCP Program’s Performance Information Profile (2017) (PIP). Facilitated by an external resource and insights introduced through the conduct of this evaluation, this framework was updated by ECCP Program representatives while the evaluation was in progress.

The results of this evaluation will help inform the design of the ECCP Program as this framework is further updated by the Low Carbon Energy Sector (LCES). The evaluation also provides insights that can be applied to improve the design and delivery of other policy functions at NRCan.

What the Evaluation Found

Program Design

We found that the Energy Policy Branch’s understanding and articulation of the ECCP Program’s design continues to evolve and improve. Measuring the performance of policy functions is a complex activity. Over most of evaluation period, the ECCP Program had a weak performance measurement framework resulting in important gaps in the availability and utility of its performance information. However, since 2018, the ECCP Program has been undertaking substantive efforts to improve its PIP, including the Program description, results logic and performance metrics.

Analysis completed in support of this evaluation confirms the revised results logic for the ECCP Program, i.e., that the Program’s activities, outputs and outcomes have been appropriately identified and that it is reasonable to expect that the Program’s activities should lead to its intended outcomes. Our analysis also expands on progress to date to further the development of the theory of change for the ECCP Program and identify additional options that the ECCP Program could explore as it develops its performance metrics. The measures that will be implemented need to reinforce the value of the Program based on, for example, the nature of stakeholder relationships or its ability to reframe understanding of a policy issue.

Relevance

The ECCP Program is relevant to federal government and NRCan priorities for energy and climate change. Revisions to the Program’s logic model effected in response to the reorganization of the Energy Sector now focus outcomes more clearly on advancing Canada’s low-carbon energy and climate change priorities. There is still a need for further clarification in some areas, such as the extent to which Program priorities should include climate change adaptation.

The evaluation also found that the ECCP Program’s activities are relevant to the needs of key stakeholders. Particularly given shared jurisdiction for energy and climate change, stakeholder engagement is fundamental to the effectiveness of the ECCP Program. Overall, we found that appropriate target audiences have been engaged or reached. It is not possible in the absence of a clear engagement plan to fully assess the adequacy of these collaborations. Regardless, evidence suggests a need to increase engagement in some areas, particularly with those groups that are generally underrepresented in policy development and implementation (i.e., women, youth, and Indigenous peoples). The ECCP Program’s Equal by 30 Campaign is noted as a positive example in this regard.

Program Delivery

This evaluation reviewed the extent to which the conditions and external factors identified in the theory of change are being met by the ECCP Program and/or are otherwise impacting the delivery of its program activities. Overall, there is evidence of effective program delivery but with some room for improvement. Across the five categories included in the theory of change, we found that:

- Process Management: There is evidence of effective process management in response to stretched resources, with human and financial resources allocated as required to address priorities. However, these resources may not be aligned with current or future work demands given the increasing number and scope of federal energy and climate change initiatives. Evidence suggests that the Energy Policy Branch could be more effective at securing durable funding to support these initiatives. While the competency of existing staff is considered a strength of the Program, there have been issues with recruitment and retention of staff including for senior management (EX) positions. The reasons for this are not entirely clear.

- Quality of Policy Products: There is evidence that the ECCP Program produces quality policy products that are neutral and evidence-based. This is critical to meaningful dialogue on energy and climate change. There may be some opportunities for the Program to better reflect the perspectives of other NRCan sectors in its internal products. However, the subject matter is complex and requires a balance of interests to ensure policy products reflect those sometime divergent perspectives. There is also evidence that the ECCP Program produces quality policy products and that these are reaching target audiences. External factors (e.g., political relationships, stakeholder capacity, etc.) impact the extent to which these products influence stakeholder perspectives or result in concrete actions. The ECCP Program is actively working to launch the Canadian Centre on Energy Information, which is expected to address current gaps in access to reliable, transparent and science-based information as the evidence base to make informed decisions. This should enable both Canadians and the ECCP Program to conduct stronger economic and energy analysis.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Canada’s low-carbon energy transition cannot be achieved without collaboration. There is evidence that the ECCP Program’s policy products are reaching target audiences, but external factors (e.g., political relationships) impact the extent to which these products influence stakeholder perspectives or result in concrete actions. The ECCP Program also works to engage stakeholders and be inclusive of stakeholder perspectives in key policy exercises but some stakeholders (particularly underrepresented groups) may lack the capacity or adequate opportunities to participate. There is thus a risk that the perspectives of some stakeholders are not being collected and conveyed or that opportunities to collect fresh perspectives or new solutions are being missed. As illustrated by Generation Energy, we also found that engagement is not an end in itself. While the pathways indicated by Generation Energy have become a foundation for NRCan’s advice to the government on how to advance Canada’s low-carbon energy transition, changes to the broader policy environment impacted NRCan’s ability to begin implementing its specific recommendations. Stakeholders need to see concrete actions or there is a risk that they may disengage.

- Policy Environment: The extent to which the policy environment is supportive of the ECCP Program and its outcomes is a key external factor impacting on program delivery. As with all policy programs, policy development within the ECCP Program is largely influenced by government priorities, which can change or evolve quickly depending on the environment.

- Relative Advantage: As per the ECCP Program’s theory of change, its ability to contribute to advancing Canada’s low-carbon energy and climate change priorities requires internal and external stakeholders use its advice and analysis in decision-making. Their motivation or desire to do so also assumes that there is a real or perceived advantage to be gained from adopting the resulting policy, decision or practice. The ECCP Program currently plays an important role in understanding and integrating stakeholders’ polarized views to develop responsive policy options or solutions. Moving forward, its policy advice must continue to recognize the inherent tension between priorities for energy and the environment and actively identify opportunities to bring the two together.

Recommendations and management response

| Recommendation | Management Response |

|---|---|

|

Agreed. The ECCP Program’s PIP will be updated. This update will include a revised logic model, theory of change, and at least one indicator that is more relevant to measuring meaningful program performance. As the indicator is more experimental than in previous years, results will be tested and possibly adjusted over time based on feedback. Due date: December 31, 2020. |

|

Agreed. In 2020-21, LCES developed stakeholder engagement plans for individual policy priorities, including: the development of a hydrogen strategy and of a Small Modular Reactor action plan; consultations on radioactive waste management. Starting in 2021-22, LCES will include, as part of its annual business plan, a stakeholder engagement plan which will reflect the elements identified in the recommendation. This overall stakeholder engagement plan will provide an integrated approach to managing these activities within the context of the broader priorities of the sector. Due date: August 31, 2021. |

|

Agreed. Following the departmental reorganization that created LCES in 2019, the new Sector undertook a review of its operations which led to a reorganisation of the Branch, which was announced in June 2020. The reorganisation included the integration of the Energy Policy Branch with the international functions of the International Energy Branch, in recognition of the evolving and transforming policy space in which the Program works. A review of the operations of the new Energy Policy and International Affairs Branch is currently underway to ensure resources and tools are well aligned across its various work areas. This review will result in a plan to ensure branch capacity is aligned with its activities, including in light of its role to coordinate the implementation of NRCan’s measures in support of the government’s Strengthened Climate Plan. Due date: June 30, 2021. |

|

Agreed. The Program plays a key role in advancing the government’s priorities related to the transition to a low-carbon economy and addressing climate change, which were informed by the Generation Energy process and recommendations. The Program will develop proposed approaches to communicate to stakeholders and the public how Generation Energy informed various elements of the government’s Strengthened Climate Plan. Due date: June 30, 2021. |

Introduction

This report presents the findings, conclusions, and recommendations from the formative evaluation of the Energy and Climate Change Policy (ECCP) Program. The evaluation examines the delivery of the program over the period from 2014-15 to 2018-19. The Audit and Evaluation Branch (AEB) of Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) undertook the evaluation between December 2018 and February 2020. It was conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board (TB) Policy on Results (2016).

Formative evaluations are undertaken during program development and implementation to improve the program’s design as it is being delivered (continual improvement). Rather than judge results, their aim is to improve understanding of a program’s theory of change and, by gauging the program’s current level of performance, provide constructive feedback to program managers to facilitate improvements in design and delivery to meet program objectives. Results of this formative evaluation will help inform the design of the ECCP Program as it is updated by the Low Carbon Energy Sector.

Formative evaluations are undertaken during program development and implementation to improve the program’s design as it is being delivered (continual improvement). Rather than judge results, their aim is to improve understanding of a program’s theory of change and, by gauging the program’s current level of performance, provide constructive feedback to program managers to facilitate improvements in design and delivery to meet program objectives. Results of this formative evaluation will help inform the design of the ECCP Program as it is updated by the Low Carbon Energy Sector.

Program information

Though the Energy Policy Branch has provided this policy function for a number of years, it was not designated as a formal Program until the development of NRCan’s new Departmental Results Framework. The ECCP Program is now Program 2.11 in NRCan’s Program Inventory. This Program provides policy advice to the Minister of Natural Resources, senior government officials, and other stakeholders to inform decision-making on matters related to energy and climate, including the future pathway for Canada’s energy sector. It serves as the federal government’s central energy policy hub in the transition to a low-carbon, sustainable, inclusive and competitive resource economy.

Within its four core functions, the ECCP Program:

- Conducts economic research and analysis to support policy-making and provide the public with data, forecasting, and other information on Canada’s energy sector. This activity produces tools and information products for decision-makers and the public, such as NRCan’s Energy Fact Book and the recently announced Canadian Centre for Energy Information (CCEI).

- Conducts and consolidates policy research and analysis across energy sub-sectors (e.g., oil and gas, energy efficiency, renewables, nuclear, technology and innovation, etc.) on both energy and climate change-related issues. Key outputs of this activity include guidance, advice, and information products (e.g., studies, briefings, and policy papers) for internal decision-makers and the products of policy development (e.g., Memoranda to Cabinet and TB Submissions).

- Coordinates with department officials in both NRCan and other government department on NRCan’s participation in government-wide energy and climate change initiatives such as the Canadian Energy Strategy and Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change.

- Collaborates with energy stakeholders. Central to the ECCP Program, this includes engagement with relevant stakeholders to inform government priorities, develop and influence government agendas, promote knowledge exchange through networks and partnerships aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and to develop, influence and promote policy options that drive the sector towards a competitive and low-carbon energy future. Through these engagements, the Program works to collect and convey stakeholder perspectives to decision makers. These collaborations can be either ongoing (e.g., the annual Energy and Mines Ministers’ Conference [EMMC]) or ad hoc (e.g., Generation Energy dialogues).

Work to revise the presentation of the Program’s logic, including articulation of its expected outcomes, is still in progress (see section on Program Design).

Program Governance

This Program is under the responsibility of the Director General of the Energy Policy Branch. This Branch consists of three Divisions: (1) Strategic Energy Policy; (2) Energy and Environment Policy; and (3) Energy and Economic Analysis. Each division provides specialized policy services and expertise that support the energy transformation agenda (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Role of Energy Policy Branch Divisions

Strategic Energy Policy Division

- Integrated advice on energy transition.

- Horizontal policy coordination.

- Collaboration and engagement with energy stakeholders (e.g., Energy and Mines Ministers' Conference).

- Coordination of NRCan's participation on GOC energy committees.

Energy and Environment Policy Division

- Integrated analysis, tracking and policy advice, on energy and climate change.

- Coordination on government-wide energy and climate change initiatives.

- Policy development for workers in the energy transition.

- Expanding women's participation in the energy sector.

Energy and Economic Analysis Division

- Economic information and analysis to, e.g., support analyses of competitiveness and energy supply.

- Energy information and analysis, including leading Canada's energy reporting to the International Energy Agency.

- Canadian Centre for Energy Information.

For most of the evaluation period, the Energy Policy Branch reported to the Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM) of NRCan’s Energy Sector. In October 2019, a departmental reorganization divided responsibility for tackling priorities related to energy into three teams:

- Low Carbon Energy Sector (LCES), leading on strategic energy policy, international energy files, electrification, renewable energy and energy efficiency.

- Strategic Petroleum Policy and Investment Office (SPPIO), with a mandate to bring greater focus to the strategic priorities of Canada’s oil and gas sector in both international and domestic markets. The Office also includes the CanmetENERGY Research Centre (Devon, Alberta), working to strengthen energy partnerships with industry, provinces and academic institutions to better integrate the research driving science and innovation in the oil and gas sector, and a new special advisory role to manage emerging energy issues. The ADM SPPIO also continues to provide leadership on files related to specific major electrification projects, such as Lower Churchill and BC electrification initiatives.

- Energy Technology Sector (ETS), leading research and development to provide clean energy solutions connected to energy policy and innovation.

This reorganization recognizes that access to reliable, affordable and sustainable energy is among the top priorities for Canadians and investors. The work of these three teams is to be coordinated through a new Energy Future Committee chaired by the Deputy Minister to deliver results for Canadians.

The Energy Policy Branch is now under the responsibility of the ADM LCES. At least during this transition period, it continues to also provide policy services as required to support the ADM SPPIO. While the Branch works in close collaboration with the Energy Technology Sector, it does not provide direct policy support to this sector.

This Branch also works alongside the policy support provided elsewhere both within LCES, such as that of the International Energy Branch and of the Office of Energy Efficiency’s Demand Policy and Analysis Division, and across NRCan (e.g., ETS’ Office of Energy Research and Development; Lands and Minerals Sector’s Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Division; and Canadian Forest Service’s Science Policy Integration Branch).

Evaluation objectives and methods

This evaluation examines program delivery over the period from 2014-15 to 2018-19 (with consideration for more recent events). Since its formal designation in 2017, the ECCP Program has continued to evolve. Given this, rather than focus on achievement of results, the objective of this formative evaluation was to examine the design and delivery / implementation of the Program, and related implications for its capacity to respond to identified needs and achieve intended outcomes.

Specific evaluation questions were as follows:

Program Design

- What is the results logic of the ECCP Program?

- What are the causal relationships between the ECCP Program’s activities, outputs and its intended outcomes?

- What factors impact the ECCP Program’s ability to respond to its intended needs and achieve intended outcomes?

- To what extent is the ECCP Program collecting (or able to collect) performance information that is (or can be) used to assess its effectiveness and efficiency?

Relevance

- To what extent does the design and delivery of the ECCP Program respond to, or align with, federal government and departmental priorities?

- To what extent does the design and delivery of the ECCP Program respond to, or align with, the needs of key stakeholders?

Program Delivery

- To what extent is the ECCP Program delivered in a way that will facilitate the achievement of outcomes?

- To what extent are the human and financial resources of the ECCP Program aligned to support the delivery of relevant federal government and NRCan priorities?

In 2018, AEB worked in close collaboration with the Energy Policy Branch to develop an innovative evaluation approach that would be formative in nature (i.e., forward-looking).

The evaluation was completed in two steps:

- Identify or confirm the Program’s key stakeholders and their needs for the Program (including relevant government and departmental priorities), and confirm or revise the Program’s theory of change, i.e., its results logic and the causal relationships between its activities, outputs and outcomes.

- Examine the design and delivery of the Program since 2014-15 to assess the extent to which this enables it to respond to identified needs and achieve (or contribute to) its intended outcomes. This includes consideration of the causal relationships and different stakeholders involved or impacted at each level of the logic model and of the internal and external factors that might hinder or facilitate the Program and (to the extent possible) the nature and magnitude of their impact.

The evaluation of policy functions is relatively uncommon and not well understood. The design of this evaluation draws from the methodological practices outlined in the TB Secretariat’s draft guide on Evaluating Policy Functions: Exploring Concepts and Tools. The validity of the evaluation approach was also confirmed by an external advisor contracted for his expertise on evaluating policy programs. The evaluation further leveraged the knowledge and experience of this external resource to facilitate the integration of related best practices.

The Energy Policy Branch has remained actively involved during the conduct of this evaluation, and has worked closely with the same external resource to develop a new theory of change for its policy function, including the introduction of new approaches to measure the effectiveness of policy work. Results of this evaluation will help inform the design of the ECCP Program as it is updated by LCES.

Formative evaluation lends itself to qualitative methods of inquiry. This evaluation used four key lines of evidence, consisting primarily of qualitative data (Table 1).

Table 1: Evaluation Methods

Literature Review

A review of published literature, with a focus on identifying elements or criteria of an effective and efficient policy program and alternative approaches to increase the relevance and effectiveness or efficiency of the ECCP Program.

Key Informant Interviews

Interviews (n=55) with ECCP Program representatives, NRCan senior managers in sectors across the department, and external stakeholders such as other federal departments, provinces and territories, indigenous organizations, industry groups and other non-government organizations.

These interviews were used to obtain perspectives on program relevance, design and delivery and to test key stakeholders understanding of and/or agreement with the ECCP Program’s program theory.

Document Review

A review of program documents to gain an overall understanding of the ECCP Program and key elements of its design and delivery (e.g., activities, outputs, and stakeholders) since 2014-15.

This method also included a review of strategic documents to identify and confirm related priorities for both NRCan and the federal government.

Stakeholder Surveys

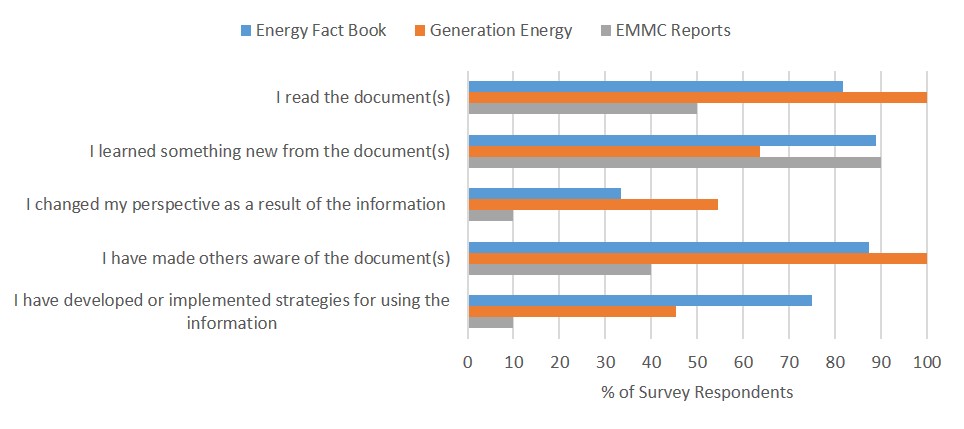

Surveys were used to measure the reach and uptake of a sample of the ECCP Program’s key products - i.e., the Energy Fact Book, Generation Energy Council Report, and outputs of the EMMC 2019.

More information on the surveys and their limitations is found in Appendix 2.

Evaluation limitations and mitigation strategies

- The starting frame for this evaluation was the Program description and results logic included in the ECCP Program’s Performance Information Profile (PIP). Recognized as deficient, this framework was updated by ECCP Program representatives while the evaluation was in progress. These updates were facilitated by an external resource and learnings introduced through the conduct of this evaluation. Related revisions, and additional changes to the Program’s design that occurred during the conduct of the evaluation (e.g., transfer of the ECCP Program’s international activities and outcomes to the International Energy Engagement Program, changes in senior leadership at NRCan impacting the ECCP Program’s governance structure) are considered in the evaluation’s analysis.

- A detailed theory of change for the ECCP Program was developed as part of this formative evaluation. As a result, there was limited information related to the extent to which the ECCP Program aligns to some conditions and external factors, as these had not yet been identified at the outset of the evaluation.

- While the evaluation conducted extensive interviews, the ECCP Program has a very broad range of targeted stakeholders. In particular, the views of representatives from industry or environmental non-government organizations may be underrepresented in the interview analysis. Where available, we mitigated this limitation by considering secondary evidence of stakeholder needs and perspectives found in program documents and literature.

- Many were generally familiar with the Energy Policy Branch, but the ECCP Program itself is not well known or understood by internal or external stakeholders. This limited the ability of these stakeholders to provide informed perspectives on program design. To mitigate this limitation, evaluators provided all interview respondents with a placemat summarizing these key design elements and results logic based on the information in the most current PIP. To the extent possible, stakeholder perspectives on program delivery were also validated against evidence presented in the document review.

- Specific challenges were encountered in the conduct of the evaluation’s surveys. These challenges and resulting limitations are outlined in Appendix 2.

What we found: program design

Summary:

We found that the Energy Policy Branch’s understanding and articulation of the ECCP Program’s design continues to evolve and improve. Since 2018, the ECCP Program has been undertaking substantive efforts to improve its PIP, including the Program description, results logic and performance metrics. These updates recognize that this policy function does more than just produce information for decisions makers. The theory of change for the ECCP Program is now described as three streams of activities (or distinct functions), each providing its own value proposition – i.e., policy as a professional service, policy as a convening function, and policy influence and oversight. The importance of engagement to its activities and outcomes achievement is now better understood and articulated.

This evaluation confirms the revised results logic for the ECCP Program, i.e., that the Program’s activities, outputs and outcomes have been appropriately identified and that it is reasonable to expect that the Program’s activities should lead to its intended outcomes. Our analysis also expands on progress to date to further the development of the theory of change for the ECCP Program and identify additional options that the ECCP Program could explore as it develops its performance metrics. Given the challenges in assessing the performance of a policy function, the ECCP Program needs to be supported and given the space to innovate and experiment with new metrics that reinforce the value of the Program based on, for example, the nature of stakeholder relationships or ability to reframe understanding of a policy issue, and not the number of products.

With respect to program design, the evaluation recommends:

RECOMMENDATION 1: The ADM of LCES should complete its update of the ECCP Program’s PIP, including revision of program theory and results logic. The ADM of LCES should also support the ECCP Program in developing and testing indicators to facilitate their use as meaningful metrics of program performance.

Understanding of the ECCP Program’s design continues to evolve and improve

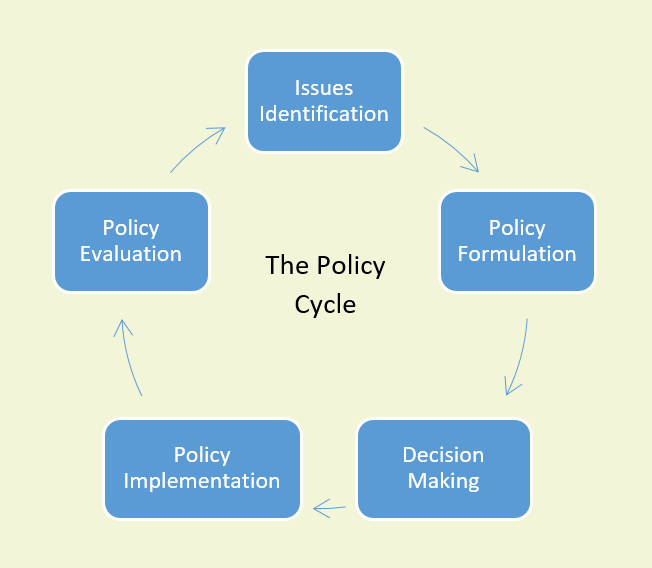

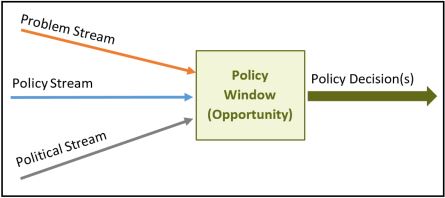

As identified in the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s draft document on Evaluating Policy Functions: Exploring Concepts and Tool, building an understanding of policy processes is an important first step in planning evaluations of a policy function such as the ECCP Program (see Box 1).

Box 1: Defining the “Policy Function”

The term “policy process” refers broadly to the ways in which policy is created and reviewed. This activity supports the foundation for program development by federal government departments and agencies.

Text version

A diagram of the policy cycle is shown with five boxes proceeding clockwise in a circle, with box one, Issues Identification at the top. Box two, Policy Formulation. Box three, Decision Making. Box four, Policy Implementation. Box five, Policy Evaluation, then returning to box one issues identification at the top to form a continuous cycle.

The organizational form of this policy process—the policy function—plays a key role in providing information, advice and coordination that informs and shapes the policy cycle. An organizational entity that engages in the policy function is referred to by a variety of terms, including policy program.

In general, the outputs and outcomes of a policy program will relate to the policy process itself and not the results of the implementation of those policies (programmatic outcomes).

The starting frame for this evaluation was the Program description and results logic included in the ECCP Program’s PIP (2017). Facilitated by an external resource and insights introduced through the conduct of this evaluation, this framework was updated by ECCP Program representatives while the evaluation was in progress. Figure 2 provides a visual presentation of the Program’s current results logic.

Analysis completed in support of this evaluation confirms the revised results logic for the ECCP Program, i.e., that the Program’s activities, outputs and outcomes have been appropriately identified and that it is reasonable to expect that the Program’s activities should lead to its intended outcomes. However, the results pathway for policy functions is complex. While presented as a linear model, the Program’s activities are actually iterative and inter-related, not discreet or linear. For example, stakeholder perspectives collected as part of engagements are used to improve information products, which in turn will be used to frame policy and refine the problem being addressed. As a result, multiple results chains with dynamic interactions are likely realized. These chains also interact with external factors that may influence the expected results. This is consistent with literature-based theory on policy development.

Figure 2: Logic Model for the Energy and Climate Change Policy Program

Activities

Conduct economic and data analysis

Conduct policy research and analysis.

Coordinate with departmental officials.

Collaborate with energy stakeholders.

Outputs

Tools and information products for decision-makers and the public.

Stakeholder perspectives are collected and conveyed to decision-makers.

Immediate Outcomes

Federal government decision-makers and stakeholders have access to tools and information to support decisions and negotiations on key energy issues.

Engagement and awareness of appropriate and necessary federal government stakeholders.

Engagement and awareness of appropriate and necessary domestic stakeholders.

Intermediate Outcomes

Use of ECCP Program advice and analysis in decisions and policies by Canadian federal government decision and policy makers.

Use of information in decisions, policies, and practices by domestic stakeholder groups.

Ultimate Outcomes

Canada’s low-carbon energy and climate change priorities are advanced.

Assumptions and External Factors

Text version

Figure 2. Logic Model for the Energy and Climate Change Policy Program. The logic model is shown as a series of boxes in five columns proceeding from left to right. The first column, activities. One, conduct economic and data analysis. Two, conduct policy research and analysis. Three, coordinate with departmental officials. Box four, collaborate with energy stakeholders. Proceeding to the second column, outputs. One, tools and information products for decision makers and the public. Two, stakeholder perspectives. Proceeding to column three, immediate outcomes. One, federal government decision-makers and stakeholders have access to tools and information to support decisions and negotiations on key energy issues. Two, engagement and awareness of appropriate and necessary federal government stakeholders. Three, engagement and awareness of appropriate and necessary domestic stakeholders. Proceeding to column four, intermediate outcomes. One, use of Energy and Climate Change Policy Program advice and analysis in decisions and policies by Canadian federal government decision and policy makers. Two, use of information in decisions, policies, and practices by domestic stakeholder groups. Proceeding to the final column five with a single box, ultimate outcomes, Canada’s low-carbon energy and climate change priorities are advanced. One rectangular element labelled assumptions and factors, underlies all phases of the logic model with two-way connections between the assumptions and factors and the rest of the logic model.

As shown in Figure 2, recent updates to the Program’s PIP effected by the Energy Policy Branch also recognize that this policy function does more than just produce information for decisions makers. The theory of change for the ECCP Program is now described as three streams of activities (or distinct functions), each providing its own value proposition. These include:

- Policy as a professional service: This area relates to the activities and outputs that are the core work of any policy group. This includes organizing data, conducting research and analysis, and preparing written and oral presentations to ensure internal and external stakeholders have the information they need to make decisions. For the ECCP Program, it also includes providing policy support to senior management and central agencies to advance key energy priorities, coordinating and reporting on NRCan’s contributions to Government-wide energy and climate change initiatives, and conducting economic and statistical analysis of energy issues for departmental officials, stakeholders, and international partners. This category of work supports the higher-level outcomes related to policy as a convening function and policy influence and oversight.

- Policy as a convening function: This area relates to the ECCP Program’s activities, outputs and immediate outcomes. It includes ensuring resources are appropriately applied to consulting, coordinating and other key functions to enable a collaborative forum or group that represents a target community on a specific energy- or climate change-related issue. This engagement approach enables two-way constructive feedback of participants to become aware of the policy development process and to provide input into related proposals. Convening is now recognized as critical to the results of the ECCP Program. This is a fundamental shift in program design; pre-existing logic models lacked any trace of effective engagement as part of the program theory.

- Policy influence and oversight: This area relates to the ECCP Program’s activities, outputs, immediate and intermediate outcomes. It includes various activities that lead to key policy outputs (e.g., guidance or options), and which reach a key target community or user. These groups are reached and engaged in a constructive dialogue, which leads to an improved understanding of the policy impact and approach. Through information sharing, evidence and constructive dialogue, those influenced by the approach make decisions to accept and implement the policy, leading to broader systemic changes in the energy system.

The evaluation used evidence collected from each of its methods to further the development of the theory of change for the ECCP Program (Appendix 1). This model considers:

- The ECCP Program’s results logic (logic model);

- The causal relationships that explain the results logic;

- The conditions and external factors that influence its intended outcomes; and

- The ECCP Program’s spheres of influence.

Box 2: What is a Theory of Change?

What is a Theory of Change?

While logic models tend to focus solely on describing a program’s intended results (the results chain), theories of change also explain how and why an intervention is expected to bring about its targeted sequence of results, with explicit consideration for the conditions and external factors that may influence the achievement of outcomes.

There are numerous conditions and external factors that influence the ECCP Program’s intended outcomes. The model in Appendix 1 regroups these into five broad categories:

- Process Management. Process management includes having and making effective use of human resources, financial resources, and available tools (e.g., information technology and data access), as well as adequate leadership direction and support.

- Quality of Policy Products. Policy products include written and oral outputs of the policy process (e.g., briefing notes, discussion papers, TB submissions, published reports, presentations, briefings, etc.).

- Stakeholder Engagement. Stakeholder engagement includes ensuring that the “right” internal and external stakeholders are engaged, targeted to receive information, and are receptive to the information conveyed.

- Policy Environment. The ability of the ECCP Program to contribute to its outcomes depends on the extent to which there is a motivation and opportunity within the federal government and among external stakeholders to enact energy and climate change policy and provide resources to support policy development and implementation. This is a dynamic space where government priorities ultimately dictate policy decisions.

- Relative Advantage. The ability of the ECCP Program to contribute to its outcomes assumes stakeholders favour the information in its policy products over competing sources, and that there is a real or perceived advantage to be gained by using this information in decisions, policies and practices. It also assumes balanced trade-offs can be achieved.

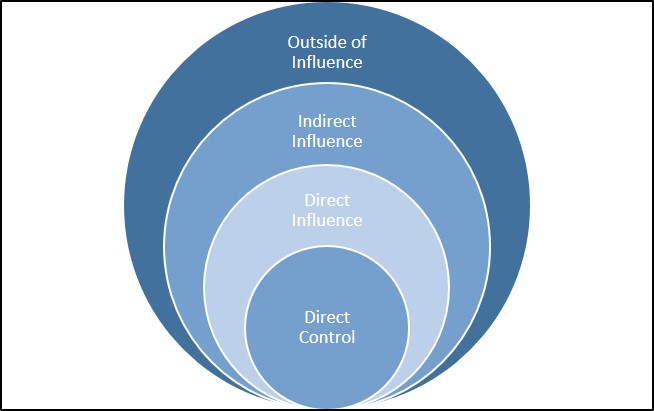

Spheres of influence are also an important consideration in this analysis (Figure 3). All conditions and contextual factors – including those that cannot be controlled or influenced – will impact program effectiveness. While many elements in the theory of change for the ECCP Program are within its direct control or influence, as with all programs, as you move up the results chain this control weakens and it becomes harder to attribute results directly to program interventions. For example, the ECCP Program can control who it invites to participate in an engagement but cannot control which stakeholders decide to participate. Similarly, it can influence the uptake of advice and analysis by promoting awareness of its products or tools, but cannot control the extent to which stakeholders use this information to make decisions. Additional actions the ECCP Program can take to increase its relevance or improve its design and delivery must consider this influence, but need not necessarily be limited to the sphere of “direct control”.

Figure 3: Spheres of Program Influence

Text version

Figure 3. Spheres of Program Influence. Spheres of influence are shown as a series of four rings, lying within each other. The diagram starts with ring one, direct control at the centre. This proceeds to ring two, direct influence further from the centre, and continues to ring three, indirect influence, and finally ring four, outside of influence, furthest from the centre.

We encourage the ECCP Program to consider the conditions and external factors in the theory of change presented in this evaluation report as it moves forward with reviewing and revising its program design and performance metrics.

Improvements are needed in the availability and utility of performance information

There are a number of theory-based approaches to evaluation, with one common feature – all develop a theory of change for the intervention and then verify the extent to which the theory matches what is observed. Similarly, the next step in our analysis was to review performance, i.e., the extent to which the conditions identified in the theory of change are being met by the ECCP Program and/or are otherwise impacting its delivery.

Literature supports both the value and challenge of measuring the performance of policy functions. As described by the Office of the Auditor General (OAG) Manitoba in its Guide to Policy Development (2003), in the absence of information on how previous policies or the policy process have worked, policy development can be an exercise of “shooting in the dark” and risks perpetuation of policy approaches that may not be working. Relying on complaints or ad hoc feedback from clients and stakeholders can create a false sense of security.

Yet, as discussed, the policy process is complex. Approaches to performance measurement that work well for the rest of NRCan’s programs may not work as well when applied to a policy program. There is an inherent, acute challenge in attributing outcomes to the specific activities or outputs of a policy function. Metrics tend to be quantitative and focus on production of outputs rather than achievement of outcomes, or focus only on decisions and actions (e.g., proportion of recommendations adopted), which can be heavily impacted by external factors.

Over most of the evaluation period, the ECCP Program has had a weak performance measurement framework. While it was able to produce metrics required for corporate reporting (e.g., NRCan’s contributions to the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy or Pan-Canadian Framework), these publically reported metrics tend to focus on policy implementation (program outcomes), not policy development. Evaluation evidence also suggests that the Program has lacked adequate tools, processes and mechanisms to effectively monitor and report performance. There are thus important gaps in the availability and utility of its existing performance information.

However, since 2018, the ECCP Program has been undertaking initiatives to improve its performance metrics. For example, its recent survey on the knowledge and uptake of the Energy Fact Book (see Appendix 2) was a test of the utility of this survey tool as an indicator of the extent to which recipients (i.e., decision-makers or influencers), directly or indirectly, use policy products, initiatives and/or activities to inform or advance a desired policy outcome. Given the challenges in assessing the performance of a policy function, the ECCP Program needs to be supported and given the space to innovate and experiment with new metrics. Informed by this evaluation, the measures that will be implemented need to reinforce the value of the Program based on, for example, the nature of stakeholder relationships or ability to reframe understanding of a policy issue, and not the number of products (see generic examples in Table 2).

The ECCP Program has also recently added metrics related to the CCEI to its PIP. While the feasibility of data collection based on these metrics has yet to be tested, they do show potential as useful performance metrics related to both the quality and uptake of energy information.

Table 2: A Basic “Menu” of Metrics for Measuring the Results of Policy Programs

| Result | Influence of Policy Program on Result | “Menu” of Policy Result Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Engagement |

|

|

| Reactions |

|

|

| Learning |

|

|

| Decisions and Actions |

|

|

Source: Adapted from S. Montague (2014)

The evaluation’s literature review was also useful in identifying additional options that the ECCP Program could explore as it develops its specific performance metrics. Besides direct measures of the Program’s outputs and outcomes, this list suggests measures of conditions influencing outcome achievement identified in the theory of change (Appendix 1). This includes:

- Product Quality. Linked to ‘reactions’ and ‘learning’ in Table 2, this could include qualitative assessments of policy product attributes against set criteria for product quality on a sample of “key” products, either by self-assessment or with stakeholder feedback.

- Collaboration. Linked to ‘engagement’ in Table 2, this could include a survey of levels of collaboration and/or stakeholder satisfaction with engagement. To be truly meaningful, the results of this assessment would ideally be compared to targets or objectives in a stakeholder engagement plan.

- Awareness and Use. Linked to ‘learning’ and ‘decisions and actions’ in Table 2, this could include measures of the knowledge, use and uptake of “key” products. As noted, the ECCP Program is already considering a related indicator and assessing the various methods via which this information can be collected, e.g., stakeholder surveys, citation analysis, and web analytics.

- Constructive Dialogue. Linked to the ECCP Program’s ultimate outcome (and the importance of ongoing stakeholder collaboration in achieving this end), indicators in this category would reflect on the Program’s ability to effectively use its evidence base and convening function to frame policy and encourage positive systemic changes. The feasibility of measuring the degree of polarization in the energy and climate change policy discourse was recently demonstrated in a survey completed by Positive Energy, supported with funding from the ECCP

ProgramFootnote 1. Data collected to support such measures could also be used to identify core challenges and opportunities in building public confidence in government decisions on Canada’s energy future.

Metrics for outputs or immediate outcomes could be relatively easy to operationalize. However, particularly given the importance of external stakeholders in achieving the Program’s outcomes, as one moves up the results chain, these metrics become increasingly complex (but would also be measured with less frequency). While many of these metrics would involve an incremental cost to the Program, they would help shift the focus from the effectiveness of policy implementation (i.e., program outcomes such as emissions reductions) to policy development and could provide very valuable information for program management.

What we found: Relevance

Summary:

The federal government and NRCan have clear priorities for energy and climate change. We found that the ECCP Program has responded effectively to shifts in these priorities and that its role in addressing related challenges has increased the relevance of the Program over time. However, it is not always clear exactly which priorities the ECCP Program is looking to advance. While revisions to the Program’s logic model effected in response to the reorganization of the Energy Sector now focus outcomes more clearly on advancing Canada’s low-carbon energy and climate change priorities, evidence indicates that the Program’s work in some energy-related areas may still go beyond this expected outcome. Internal stakeholders also noted the need to clarify the extent to which climate change adaptation is included in the Program’s priorities.

The evaluation also found that the ECCP Program’s activities are relevant to the needs of key stakeholders and appropriate target audiences are being reached. However, with some exceptions, it is challenged to maintain its overall network of external stakeholder contacts in this crowded and continuously evolving policy space. The Program may also need to increase engagement in some areas. Special consideration should be given to engagement with those groups that are generally underrepresented in policy development and implementation (e.g., women, youth, and Indigenous peoples), such as that demonstrated by the ECCP Program’s Equal by 30 Campaign.

With respect to program relevance, the evaluation recommends:

Recommendation 2: Working as required with other sectors, the ADM of LCES should build on the learning from this evaluation to develop and maintain a stakeholder engagement plan for the ECCP Program. This plan should consider the following elements:

- Who needs to be consulted / engaged, and for what reasons;

- The nature or level of collaboration desired in engagements;

- Mechanisms to engage underrepresented groups;

- Mechanisms to maintain networks of key contacts; and

- Feedback loops required to inform stakeholders of the results of collaborations.

The ECCP Program is aligned with federal government and NRCan priorities

The federal government and NRCan have clear priorities for energy and climate change. The Government of Canada recognizes that strong action to address climate change is critical and urgent. As a party to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Canada ratified the Paris Agreement in 2016, with a target to reduce Canada’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030. In 2019, the federal government further pledged to reduce Canada’s GHG emissions to “net zero” by 2050.

The Government of Canada also recognizes that energy will play an integral role in meeting these commitments, given that energy production and use accounts for over 80% of Canada’s GHG emissions (Figure 4). Canada’s energy transition will require using low-carbon energy to power our homes, workplaces, vehicles, and industries, and using energy more efficiently.

Box 3: Low-Carbon Energy

Low-Carbon Energy – The energy produced from sources that produce no or limited carbon emissions (e.g., hydro, wind, solar, nuclear, geothermal, biomass and tidal). This definition could also include low carbon fuels and energy efficiency solutions.

The sustainable development and integrated management of natural resources, including energy, is central to NRCan’s mandate. As outlined in the Departmental Plan 2019-20, NRCan has a core responsibility to lead the transformation to a low-carbon economy by improving the environmental performance of Canada’s natural resource sectors through innovation and sustainable development and use.

While we found the ECCP Program to be relevant across the entire evaluation period, documents indicate a shift in priorities over time. Since fall 2015, the federal government has maintained its focus on increasing market access for natural resources and creating jobs for the middle class. However, it has increased its focus on a strong economy as being linked to a healthy environment. Mandate letters for the Minister of Natural Resources also indicate a responsibility to engage with Canadians and collaborate with stakeholders (particularly provinces and territories), with considerations for inclusion of underrepresented groups. The federal government has also placed an increased emphasis on transparency, open government, and evidence-based decision making across policy fields, including for energy and climate change.

Figure 4: Where Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions come from

Source: ECCC - National Inventory Report 1990-2018: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada

Text version

Figure 4: Where Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions come from. Oil and Gas, 26%. Transportation, 25%. Buildings, 13%. Heavy Industry 11%. Agriculture, 10%. Electricity, 9%. Waste and Others, 6%. Source: National Inventory Report 1990-2018: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada (Environment and Climate Change Canada).

We found that the ECCP Program has responded effectively to these shifts and that its role in addressing related challenges has increased the relevance of the Program. For example, the ECCP Program played a key role in leading NRCan’s contributions to federal actions in the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change (2016).

While this provides strong evidence of alignment to federal and NRCan priorities, evidence also indicates that over the period of evaluation it was not always clear exactly which priorities the ECCP Program was looking to advance. The challenge of identifying clear program outcomes is one frequently observed in the design of policy programs, with outcome statements that are somewhat vague in theory supporting the flexibility to be responsive to new or shifting priorities as they emerge. While the focus in the ECCP Program’s outcome statements is now more clearly on advancing Canada’s low-carbon energy and climate change priorities, evidence indicates that the Program’s work in some areas (e.g., analyses of competitiveness and energy supply, ongoing policy support to SPPIO) may go beyond this expected outcome. To some extent, this is a legacy issue from when NRCan still had a single Energy Sector. At the same time, the evaluation recognizes that this is a challenging policy space where there is a need to balance the narrative. Program representatives also note that the sustainable development and competitiveness of energy resources and advancement of climate change objectives are not mutually exclusive, and the ECCP Program aims to bring the two together.

As NRCan’s primary program dedicated to climate change policy, most stakeholders believed that the ECCP Program needs to integrate consideration for the department’s full suite of policies related to the intersection of energy and climate change. Specifically, many noted that the Program’s outcome statements are not specific to climate change mitigation. Long-term trends in energy are influenced primarily by factors such as changes in population, economic activity, energy prices, clean energy technology and energy efficiency. However, research indicates that many aspects of energy demand, supply, and transmission are sensitive to climate variability and will be impacted by various dimensions of climate change, including higher temperatures, changing frequency and intensity of extreme events and changes in water availability (Figure 5). The net annual result of climate change-induced shifts will be country and region specific, and will be influenced by the actions taken to adapt to predicted effects.

Figure 5: Examples of predicted climate change impacts on Canada’s energy sector

Source: Lemmen et al. (2014) and USGRCP (2017)

Text version

Figure 5: Examples of predicted climate change impacts on Canada’s energy sector.

Increased energy demand.

- increased peak electricity demand due to rising temperatures.

- changes in seasonal energy demand for heating / cooling.

Fluctuating energy supply

- changes in hydropower production due to varying precipitation.

- increased biofuel availability due to pests, fires, droughts, etc.

- changes in wind and solar intensity due to climate variability.

- reduced water for onshore oil and gas production.

Decreased transmission reliability

- damage to infrastructure (eg., pipelines, towers, transmission lines) from extreme weather events and permafrost melt, resulting in decreased grid reliability and increased power interuptions.

- decreased efficiency of conductors due to ice and snow build-up.

Threats to energy security & human health

- increased frequency of fuel shortages, increased fuel prices in remote locations.

- health effects of increased extreme heat days in urban areas.

While there are discussions on climate change adaptation in many of the ECCP Program’s policy products, we observed opportunities for more in-depth presentation of these connections in program outcomes and implementation. NRCan’s Climate Change Adaptation Program (Program 1.9) also provides policy support in this area. Nevertheless, given differences in the drivers and key actors for climate change mitigation and adaptation, internal stakeholders engaged in adaptation suggested that their input should be sought earlier in related policy development and be given more weight in approval of related content for senior officials.

The activities of the ECCP Program are aligned to the needs of key stakeholders

All of the ECCP Program’s activities were found to be important enablers for the Program and relevant to the needs of key stakeholders. Perceptions of the relative importance of each activity varied by stakeholder group, often in reflection of the bias of a particular stakeholders’ mandate. For example, those who work in the area of energy information and statistics were more likely to see economic research and analysis as a critical activity.

The ECCP Program’s economic research and analysis meets a need for decision-makers to access high-quality information to make, validate and communicate policy-related decisions. The ECCP Program plays an important role as an “honest broker” in the provision of non-biased, evidence-based energy information.

However, research also shows that most Canadians have a poor understanding of energy policy and related issues. Ensuring access to neutral, evidence-based information about energy systems and the potential impacts (positive and negative) of diverse approaches to achieving Canada’s energy future is thus critical to meaningful dialogue. This is a need that could be addressed by the ECCP Program, provided it can find levers through which to more effectively communicate to Canadians the role and importance of energy. At present, evidence indicates that the energy information provided by the ECCP Program and other data providers does not adequately meet the needs of key stakeholders. This latter gap is expected to be addressed by the CCEI (see Box 4).

Similarly, there is a strong internal demand for integrated policy analysis and advice. The need for intra- and inter-departmental policy coordination has increased over the period of evaluation as the federal government has introduced new commitments and initiatives related to energy and climate change.

Box 4: The Canadian Centre for Energy Information (CCEI)

The CCEI was announced in Budget 2019. When launched, its user-friendly website will ensure individuals and communities have free access to reliable, transparent and science-based energy information as the evidence base to make informed decisions. The CCEI will be administered by Statistics Canada under a client-service agreement with NRCan. NRCan’s work to develop the CCEI is being led by the ECCP Program.

The evaluation found that these professional services are mostly reactive (e.g., in response to specific issues, events or information requests). The Energy Policy Branch has also been vocal about the need for more space and time to conduct policy research. While literature suggests that this is relatively typical of a policy function, recently the Branch has undertaken more anticipatory research and analysis work to support program renewals and meet the needs of internal stakeholders. Senior managers have also begun exploring how the ECCP Program can be supported to further develop its capacity to engage in proactive foresight and pre-emptive policy research and analysis exercises.

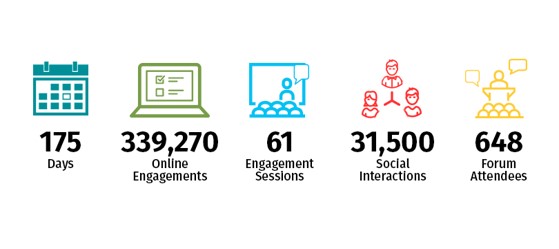

By contrast, the ECCP Program’s activities related to collaboration with stakeholders are relatively proactive and policy driving. The debate on energy and climate change is heavily polarized. The ECCP Program plays an important role in understanding and integrating stakeholders’ polarized views to develop informed policy options or solutions. The number and breadth of stakeholders that engaged in the Generation Energy dialogues convened by the ECCP Program in 2017 (an estimated 380,000 Canadians) is a clear indication of stakeholder needs in this area. However, the evaluation’s interviewees indicated that this activity could be better linked with outcomes, i.e., that engagement is not an end in itself. Stakeholders need to see concrete actions as a result of their engagements, both to ensure their priorities are addressed and as a pay-off for the investment of their time. This issue is further discussed under Program Delivery.

The ECCP Program requires a process to effectively engage key stakeholders

Literature-based theory on the design of policy programs strongly supports a need to consistently and actively engage a broad community of stakeholders in policy development.Footnote 2 Policy issues tend to have horizontal implications, involving more than one department, level of government and/or other external stakeholders. There is also an assumed or, in some cases, a legislated need to consult Canadians to inform government decisions. The quality of policy advice and decisions depends on the integration of these stakeholders and their perspectives into the policy process.

While important for most programs, we found that stakeholder engagement is a fundamental consideration for energy and climate change policy. The ECCP Program is not the only program within NRCan or the Government of Canada concerned with either issue. Similarly, jurisdiction for energy policy is shared between the federal and provincial governments. Climate change also has the potential to impact everyone. Energy and climate change is thus a crowded policy space with a low barrier to entry (e.g., where a single teenager can start an entire movement), within which stakeholder groups are rapidly evolving.

Developing and maintaining stakeholder relationships takes time and effort. The large number of governance bodies for energy and climate change within the federal government itself, let alone external networks, makes this engagement environment very complex and energy intensive and, even where there is concerted effort to do so (e.g., the Equal by 30 Campaign), the ECCP Program is challenged to maintain its network of external stakeholder contacts. Numerous external stakeholders, including provincial and territorial governments, also noted that they lacked a clear “window of access” (contact) when they wanted to initiate engagements with NRCan related to energy and climate change.

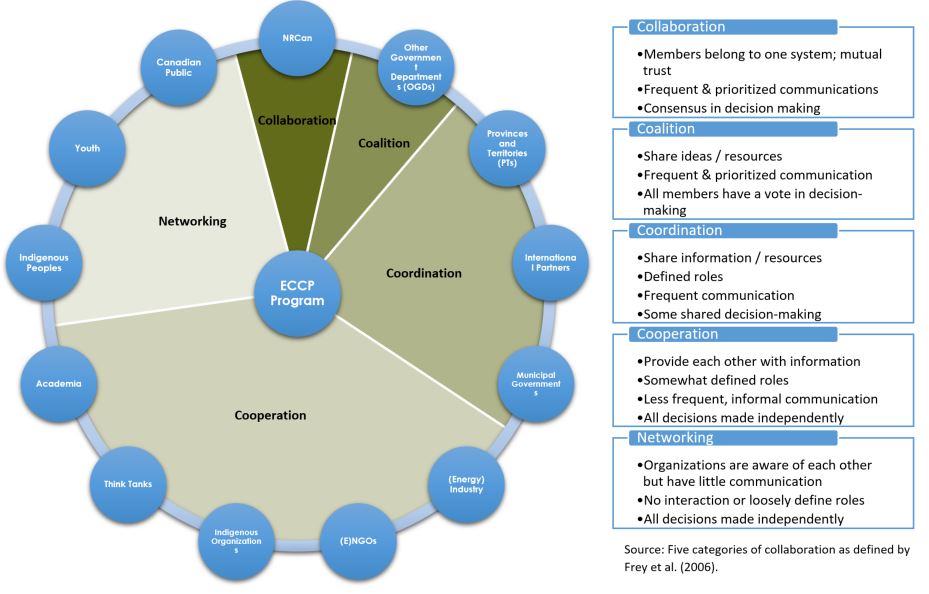

Overall, we found that appropriate target audiences have been engaged or reached by the ECCP Program. Figure 6 presents a summary of the categories of key stakeholders and their current level of collaboration with the ECCP Program observed by the evaluation. Moving clockwise around the circle of this collaboration map, we found regular or frequent and formalized engagement with some key stakeholder groups (i.e., the rest of NRCan, other government departments, provincial and territorial governments) and less frequent or formal engagement with others. However, note that this is a simplified presentation. Most categories can be further broken out into sub-groups (e.g., division of “industry” into traditional and emerging clean energy, energy producers and energy consumers), each with differing policy priorities and stakeholder networks. The figure does not identify the intersections among different categories of stakeholder (e.g., Indigenous youth).

The evaluation could not conclude on whether the observed level of collaboration with each stakeholder category is appropriate. While target audiences are defined for some specific initiatives, the ECCP Program as a whole has yet to define its desired level of collaboration with each of category of key stakeholder. For example, while the evaluation identified the relationship with Indigenous organizations as one of cooperation (i.e., where groups may provide each other with information but do not engage in frequent, formal communications or share any decision-making), there is no evidence that would identify whether this as the ECCP Program’s desired level of engagement.

Nonetheless, we did identify potential gaps. For example, policy advice is being increasingly offered to decision-makers from sources such as think tanks, industry and academia and more work is required to engage stakeholders in this area. The ECCP Program is encouraged to continue with recent progress made in increasing its collaboration with these groups. Program staff and external stakeholders also expressed a need to increase engagement in some areas, particularly with those groups that are generally underrepresented in policy development and implementation (i.e., women, youth, and Indigenous peoples) and in the intersection among these groups. The ECCP Program’s Equal by 30 Campaign (Box 5) demonstrates a desire and commitment to make progress in this area, at least as it relates to gender equity.

Box 5: Equal by 30 Campaign

Equal by 30 is a commitment by public and private sector organizations to work towards equal pay, equal leadership and equal opportunities for women in the clean energy sector by 2030. The Equal by 30 Campaign asks companies and governments to endorse principles, and take concrete actions to help close the gender gap. This campaign presently has more than 130 signatories, who are actively engaged in work to enhance women’s equality in the energy sector.

This progress is positive. However, given that engagement is a fundamental consideration for energy and climate change policy, the ECCP Program would benefit from a stakeholder management plan to clearly identify who it wants to engage with, for what purpose or to what level of collaboration, and the mechanisms by which it intends to engage. Besides facilitating relationships with key partners and stakeholders, such a plan would also be a useful benchmark against which to measure progress on the program’s outcomes related to engagement.

Figure 6: ECCP Program Collaboration Map (indicates the current level of engagement of the ECCP Program with its key stakeholders

Source: Five categories of collaboration as defined by Frey et al. (2006).

Text version

Figure 6. ECCP Program Collaboration Map (indicates the current level of engagement of the ECCP Program with its key stakeholders). The diagram consists of a circle, divided into five sectors or collaboration areas of varying sizes. Each sector is labelled with a type of collaboration, and is further described by a box to the right of the diagram. Circles with different types of stakeholders are positioned along the circumference of the outer circle, and are associated with one of the diagram’s sectors representing the collaboration area. The Energy and Climate Change Program lies in a smaller circle at the centre of the diagram. Starting from the top and working clockwise, the smallest sector of the diagram is collaboration, and is associated with Natural Resources Canada stakeholders. The box on collaboration describes three points. Bullet one, members belong to one system, mutual trust. Bullet two, frequent and prioritized communications. Bullet three, consensus in decision making. The second sector, equal in size to the first, is coalition. It is associated with Other Government Departments. The coalition box has three points. Bullet one, share ideas and or resources. Bullet two, frequent and prioritized communication. Bullet three, all members have a vote in decision-making. The third sector, approximately one-fifth of the diagram, is coordination. This sector is associated with three stakeholder types. One, provinces and territories. Two, international partners. And three, municipal governments. The coordination box has four points. Bullet one, share information and or resources. Bullet two, defined roles. Bullet three, frequent communication. Bullet four, some shared decision making. The largest sector of the circle is cooperation, which is approximately two fifths of the diagram. This sector is associated with five stakeholder types. One, the (energy) industry. Two, environmental non-governmental organizations or non-governmental organizations. Three, Indigenous organizations. Four, think tanks. Five, academia. The cooperation box has four points. Bullet one, provide each other with information. Bullet two, somewhat defined roles. Bullet three, less frequent, informal communication. Bullet four, all decisions made independently. The fifth and final segment, approximately one fifth of the diagram, is networking. This sector is associated with three stakeholder types. One, indigenous peoples. Two, youth. Three, the Canadian Public. The networking box has three points. One, organizations are aware of each other but have little communication. Two, no interaction or loosely defined roles. Three, all decisions made independently. Source, Five categories of collaboration as defined by Frey and others (2006).

What we found: Program Delivery

Summary:

This evaluation reviewed the extent to which the conditions and external factors identified in the theory of change (Appendix 1) are being met by the ECCP Program and/or are otherwise impacting program delivery. Overall, we found that:

- Process Management: There is evidence of effective process management in response to stretched resources, with human and financial resources allocated as required to address priorities. However, these resources may not be aligned with current or future work demands given the increasing number and scope of federal energy and climate change initiatives.

- Quality of Policy Products: There is evidence that the ECCP Program produces quality policy products that are neutral and evidence-based. This is critical to meaningful dialogue on energy and climate change. There may be some opportunities for the Program to better reflect the perspectives of other NRCan sectors in its internal products. However, the subject matter is complex and requires a balance of interests to ensure policy products reflect those sometime divergent perspectives. There is also evidence that these policy products are reaching target audiences, but external factors impact the extent to which these products influence stakeholder perspectives or result in concrete actions.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Canada’s low-carbon energy transition cannot be achieved without collaboration. The ECCP Program works to engage internal and external stakeholders and be inclusive of stakeholder perspectives in key policy exercises but some external stakeholders (particularly underrepresented groups) may lack the capacity or adequate opportunities to participate. As illustrated by Generation Energy, engagement is not an end in itself. Stakeholders need to see concrete actions or there is a risk that they may disengage.

- Policy Environment: The extent to which the policy environment is supportive of the ECCP Program and its outcomes is a key factor impacting on program delivery. As with all policy programs, policy development within the ECCP Program is largely influenced by government priorities, which can change or evolve quickly depending on the environment.

- Relative Advantage: For the ECCP Program’s outcomes to be achieved, stakeholders must identify a real or perceived advantage to be gained from adopting a new policy, decision or practice. Moving forward, its policy advice must continue to recognize the inherent tension between energy and the environment and actively identify opportunities to bring the two together.

With respect to program delivery, the evaluation recommends:

RECOMMENDATION 3: The ADM of LCES should conduct an internal review of the ECCP Program’s business processes to identify resources and tools available for program delivery, and develop a plan to ensure that its capacity to deliver continues to be aligned with activities.

RECOMMENDATION 4: The ADM of LCES should “close the loop” on Generation Energy by providing stakeholders that engaged in the dialogues periodic updates on the actions taken to date and/or future government commitments.

There is effective process management

As noted in the section on Program Design, process management includes having and making effective use of human and financial resources, and available tools (e.g., information technology and data access), as well as adequate leadership direction and support. Theory suggests that a policy function with inadequate inputs is more likely to have a short-term focus on “fighting fires” than developing policy foresights. Risks of inadequate process management include untimely or poor quality policy products. It can also create issues for staff retention, if good quality analysts are alienated by inadequate leadership.

Conditions and contextual factors related to process management are mostly within the control or direct influence of the ECCP Program. While it cannot control human and financial resources (determined as part of departmental budgeting processes) or available tools, it can influence these factors by identifying gaps and upwardly communicating strategies to address its needs. It also has direct control over the way in which the activities it undertakes are prioritized and available resources are allocated to achieve results.

There is evidence of effective process management in response to stretched resources

While the evaluation lacks a strong basis for comparison of resource adequacy in policy programs, we can describe observable trends over the evaluation period. There is some evidence that the ECCP Program may be under-resourced to meet the observed increase in work demands, including the increased need for collaboration, planning and reporting to advance major policy priorities.

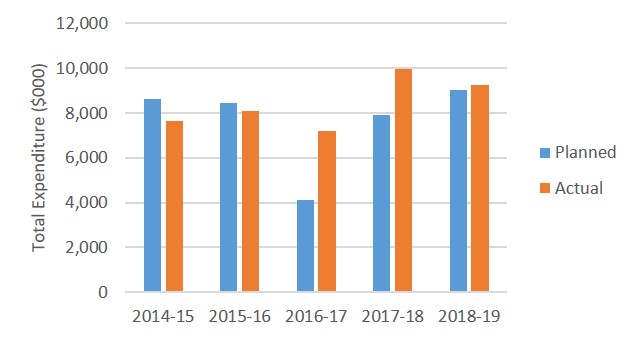

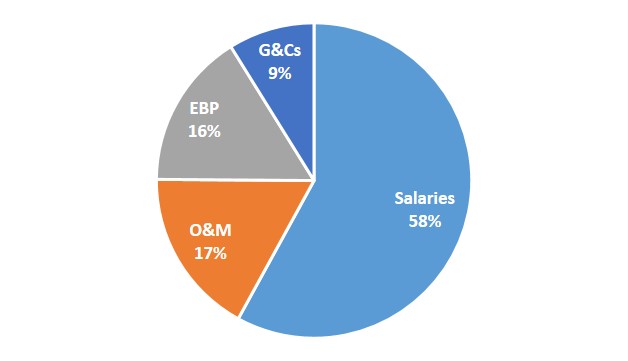

From 2014-15 to 2018-19, total planned expenditures on the ECCP Program increased slightly. The ECCP Program overspent its resources by about 11% (Figure 7). This could indicate an issue with adequate resources or the ability to effectively plan for expenditures, or it could be a symptom of the reactive policy process. For example, the largest over-expenditure (in 2016-17) was likely a result of unanticipated costs related to the Generation Energy national dialogue, as the scope of this initiative was not yet defined at the point that planned spending for 2016-17 was established.

Figure 7: ECCP Program Expenditures, 2014-15 to 2018-19

Source: Financial data provided by ECCP Program

Text version

Figure 7: ECCP Program Expenditures, 2014 15 to 2018 19. 2014 15, planned 8,605,200 dollars. Actual 7,623,800 dollars. 2015 16, planned 8,431,200 dollars. Actual 8,099,600 dollars. 2016 17, planned 4,100,800 dollars. Actual 7,191,900 dollars. 2017 18, planned 7,911,800 dollars. Actual 9,946,300 dollars. 2018 19, planned 9,019,200 dollars. Actual 9,232,800 dollars. Source. Financial data provided by the Energy and Climate Change Policy Program.

Effective process management does not necessarily require allocating more resources, but rather necessitates effective use of existing resources. Within the ECCP Program, there is evidence of allocation or re-allocation of resources to address policy priorities. Managers are also aware of staff competencies and appropriately reassign staff or reprioritize work to achieve best results within given timeframes. For example, the Energy Policy Branch re-allocated existing resources to create a task team to coordinate policy, design and logistics for the Clean Energy Ministerial 2019.