Evaluation of the Essential Geographic Information Sub-program

Table of Contents

Acronyms and Abbreviations

- CACS

- Canadian Active Control System

- CGDI

- Canadian Geospatial Data Infrastructure

- CCMEO

- Canada Centre for Mapping and Earth Observation

- CCOG

- Canadian Council on Geomatics

- CCRS

- Canada Centre for Remote Sensing

- CGS

- Canadian Geodetic Survey

- CP

- Compact polarimetry

- CSRS

- Canadian Spatial Reference System

- DORIS

- Doppler Orbitography and Radio positioning Integrated by Satellite

- DUAP

- RCM Data Utilization and Applications Program

- EODMS

- Earth Observation Data Management System

- FCGEO

- Federal Committee on Geomatics and Earth Observations

- FTE

- Full-time Equivalent

- GEM-2

- Geo-Mapping for Energy and Minerals

- GGRF

- Global Geodetic Reference Frame

- GIS

- Geographic Information Systems

- GNSS

- Global Navigation Satellite Systems

- GPS

- Global Positioning System

- IGS

- International GNSS Service

- ISSF

- Inuvik Satellite Station Facility

- ITRF

- International Terrestrial Reference Frame

- LTSDR

- Long-term Satellite Data Records

- NEODF

- National Earth Observation Data Framework

- O&M

- Operations and Maintenance

- PPP

- Precise Point Positioning

- RCM

- RADARSAT Constellation Mission

- RTK

- Real Time Kinematic

- SAR

- Synthetic aperture radar

- SGB

- Surveyor General Branch

- SLR

- Satellite Laser Ranging

- UN-GGIM

- United Nations Committee of Experts on Global Geospatial Information Management

- VLBI

- Very Long Baseline Interferometry

Glossary

Earth Observation is the gathering of data about the Earth’s physical, chemical and biological systems using satellite, airborne, waterborne and earth-based sensors. It involves monitoring and assessing the status of and changes in natural and man-made environments.

Framework data refers to the core location-based data for Canada. Also referred to as the base mapping layers required to develop applications and they are the foundation for other data layers. GeoBase data are made up of a variety of core data layers or framework data such as the Canadian Digital Elevation Data (CDED) layer; the Canadian Geographical Names Database; and the National Road and Hydro Networks.

Geodesy is the science of accurately measuring and modeling changes in the Earth’s shape, gravity field, and orientation in space.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) refers to systems of computer software, hardware and data used to capture, store, manipulate, analyze and present geospatial data. GIS typically link multiple sets of geospatial data and display the combined information as maps with different layers (e.g. roads) of information.

Geomatics (also known as geospatial technology or geomatics engineering) is the discipline of gathering, storing, processing, and delivering spatially referenced information”.Footnote 1

Geospatial data is defined as data with reference (either implicit or explicit) to a location relative to the Earth. It refers to data that can be linked to a location on a map, such as a street address, town or other geographic features such as a coastline or mountain.

Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) are satellite navigation systems with global coverage and enable the ability to rapidly determine position coordinates. The United States’ Global Positioning System (GPS) and the Russian GLONASS (Global'naya Navigatsionnaya Sputnikovaya Sistema) are global operational GNSSs.

Remote sensing is the science of acquiring information about the Earth's surface without actually being in contact with it. This is done by sensing (through various types of sensors such as radar satellite, air-borne, optical), recording, processing, analyzing, and applying that information.Footnote 2 Remote sensing is sometimes used interchangeably with “earth observation” and for the purposes of this evaluation report these terms will be used interchangeably.

Spatial reference system is a geographic coordinate (latitude, longitude, height) or reference system such as the Canadian Spatial Reference System (CSRS) and is used to locate geographical features or entities within a common, standardized geographic framework. Geographic datasets that have a well-defined coordinate system can be integrated with other datasets.

Executive summary

Introduction

This report presents the findings, conclusions, and recommendations of the evaluation of Natural Resources Canada’s (NRCan’s) Essential Geographic Information (EGI) sub-program. The sub-program is administered by NRCan’s Canada Centre for Mapping and Earth Observation (CCMEO), Strategic Policy and Results Sector (SPRS) and the Canadian Geodetic Survey (CGS), Surveyor General Branch (SGB), Lands and Minerals Sector (LMS).

Total expenditures for this sub-program were $171 million for the years 2010-11 to 2014-15. Of this $171 million, CCMEO sub-program expenditures were $147 million and CGS expenditures were $24 million. The sub-program also received $41.6 million in C-based funds for the renewal of satellite ground infrastructure as well as external funding in the amount of $15 million.

The evaluation employed a multiple lines of evidence approach, which included: document and literature reviews; 95 interviews with federal, provincial, territorial, international, academic, and industry stakeholders; five online surveys with users of geodetic services and geospatial information and with Canada Council of Geomatics (CCOG) committee members; and three case studies.

Sub-program Overview

The sub-program delivers foundation geospatial information and products, remote sensing research, satellite imagery, satellite ground infrastructure, and a standardized system of geodetic coordinates (latitude, longitude, height).

The GeoBase Initiative delivers fundamental or framework Federal-Provincial-Territorial (FPT) authoritative geospatial data (e.g., National Hydro and National Road Networks, Indigenous Lands of Canada, Administrative Boundaries, elevation data), as well as other geospatial products such as the Atlas of Canada. A key premise of GeoBase is the capacity to integrate other geospatial data layers with core data layers to enhance its usefulness for a multitude of applications and sectors. Geospatial information, including GeoBase data, is made accessible through the GeoGratis website portal and more recently through the Government of Canada Open Government Portal and the Federal Geospatial Platform. Another key principle of the GeoBase Initiative is to collect geospatial data once and use many times to enhance efficiency. It is intended to minimize duplication and to ensure the efficient provision of, and access to consistent and up-to-date base of geospatial information covering the entire Canadian landmass.

The sub-program also delivers remote sensing science that aims to ensure optimal value from remote sensing data in support of government, particularly federal government programs, operations and decision-making. Remote sensing science includes the development of earth observation technologies and applications and the creation of value-added products such as Long-term Satellite Data Records, primarily used for environmental monitoring, and enhanced satellite imagery for emergency geomatics services. The sub-program provides ground infrastructure for satellite information at three locations in Canada, and includes the recent renewal of this infrastructure. Satellite ground infrastructure is the responsibility of the Canadian Geospatial Data Infrastructure Division (CDGI), CCMEO.

Canada’s Spatial Reference System is the foundation for Canada’s positioning coordinates (longitude, latitude, height). It delivers these standardized geodetic coordinates through a network of continuous satellite tracking stations, ground monuments and data products and services enabling accurate positioning for geoscience, mapping, surveying and navigation. The maintenance of the reference system is the responsibility of the Canadian Geodetic Survey (CGS), Surveyor General Branch (SGB).

CCMEO engages federal stakeholders through the Federal Committee of Geomatics and Earth Observation (FCGEO) and provincial/territorial and federal coordination through the Canadian Council of Geomatics (CCOG). CCMEO has international responsibilities that include Canada’s head of delegation at the United Nations Global Geographic Information Management Forum; and is responsible for negotiating international treaties and agreements to promote investments in Canada relating to ground satellite infrastructures, data management, and research and development (R&D). The Canadian Geodetic Survey primarily engages provincial and territorial stakeholders through the Canadian Geodetic Reference System Committee (CGRSC) and GNSS federal stakeholders through the Federal GNSS Coordination Board (FGCB). CGS contributes data and expertise to international geodetic services and organizations primarily in support of the Global Spatial Reference System.

The creation of CCMEO was the result of merging of three branches (Mapping Information Branch, Canada Centre for Remote Sensing, and Data Management and Dissemination Branch) into one. The CGS transitioned from Canada Centre for Remote Sensing to the Surveyor General Branch in 2013. The impacts of CCMEO organizational changes and modernization activities, considered to be significant, are not expected to be fully realized for a number of years. As such, the evaluation could not assess the impacts of these changes as they are only nearing completion now. These organizational shifts were implemented by the sectors’ senior leadership cadre with the aim to improve effectiveness and efficiencies.

Evaluation Findings: Relevance

National geodetic and core geospatial data and remote sensing imagery are critical for a wide array and growing number of program, policy, operations, and research applications. Core, foundation or framework data are authoritative location-based information that underpins or adds significant value to other information. Interviews, documents, and survey evidence indicate the importance of location-based information for understanding, decision-making, and management of various issues, particularly those that support federal government priorities such as climate change, exploration and use of natural resources; hazards, public safety, sovereignty; economic competitiveness, and sustainability of lands at regional to global scales.

Canadian and international studies indicate that accessible geospatial information is an important economic driver: it is important for increasing productivity, making strategic decisions, and reducing the costs of doing business. Various jurisdictions, including Canada, have also documented that open access to geospatial and geodetic data facilitates innovation by reducing costs and information barriers. Many national governments have open government and data policies such as the United Kingdom and the United States. The Government of Canada has adopted an Open Data Policy to increase transparency and accountability and to encourage innovation and economic growth.

There is a continued important role for the federal government nationally and internationally for ensuring consistency, accuracy of, and access to, geospatial information, geodetic coordinates and services, and earth observation science and assets in Canada. NRCan and the federal government are adequately positioned to consider the requirements for geodesy and geospatial information for Canada as a whole and in consultation and collaboration with key stakeholders.

Although there has been an increase in geospatial data providers, particularly among the private sector and local governments, evaluation evidence indicates that the federal role in providing data continues to be appropriate in the following circumstances: to ensure adequate national coverage (particularly in the Northern and remote regions of Canada where the private sector is less likely to be involved) and to ensure there is adequate geospatial information to address national priorities and cross jurisdictional issues.

The federal role in providing access to remote sensing imagery is viewed by stakeholders as appropriate given the importance of remote sensing imagery for assessing, and managing issues relevant to national priorities. External stakeholders generally view the archiving of this imagery as an important role for the federal government because it is a critical source of research data and a role unlikely to be assumed by others.

The provision of geodetic programs is considered by stakeholders to be appropriate because it ensures access to consistent and accurate coordinate data, underpins other geospatial technologies and positioning and navigation systems, ensures national coverage, and serves to verify other spatial coordinate data and technologies.

The federal government should continue to provide critical and trusted national datasets, such as GeoBase framework data, although the precise nature of this role requires further clarification. Regarding GeoBase, NRCan has increasingly shifted towards a more collaborative role, which is generally viewed by stakeholders as appropriate. However, among interviewees and as reflected in the literature, there is debate as to how the federal government role should evolve. Some stakeholders indicated that the federal government must further shift towards a data verifier role with more geospatial information derived from a combination of private and public sector sources.

Evaluation Findings: Performance (Effectiveness)

The evaluation found that geospatial and geodetic information and services are consistently accessed and used, and yield benefits with respect to more informed decision-making, and enhanced programs and research. Federal and provincial government representatives noted that geospatial information has improved operational and programming decisions, and research in areas such as environmental monitoring and management, assessment of climate change impacts, emergency planning and response, hazards assessment and prediction, northern development, transportation, natural resource exploration, and sustainable use of resources.

According to international interviewees and case study evidence, the sub-program has made important contributions to international initiatives, although some decline in sub-program capacity was reported. International representatives noted that remote sensing science and mapping expertise have contributed to improved assessment of various environmental issues, such as water quality, watershed analysis, and transboundary habitat, although they indicated some decline in Canadian remote sensing and mapping capacity over the past decade. CGS provides expertise and data to support the maintenance of the Global Spatial Reference System. However, international stakeholders noted that there were some gaps in Canada’s geodetic observing infrastructure that are expected to have negative longer term implications for the accuracy of the North American and Global Reference Systems; accuracy which is needed for various science applications.

Insufficient currency of GeoBase data, accessibility issues with respect to the GeoGratis website and the imagery archiving catalogue suggest that GeoBase information and archived imagery are underutilized and therefore not achieving their full effectiveness. While the evaluation found good examples of technology transfer, NRCan and federal interviewees indicate that federal uptake of remote sensing science is constrained by insufficient federal government receptor and CCRS human resource capacities. Geospatial data products have migrated from the GeoGratis website to the Open Government Portal and the Federal Geospatial Platform. These platforms were designed to enhance efficiency.

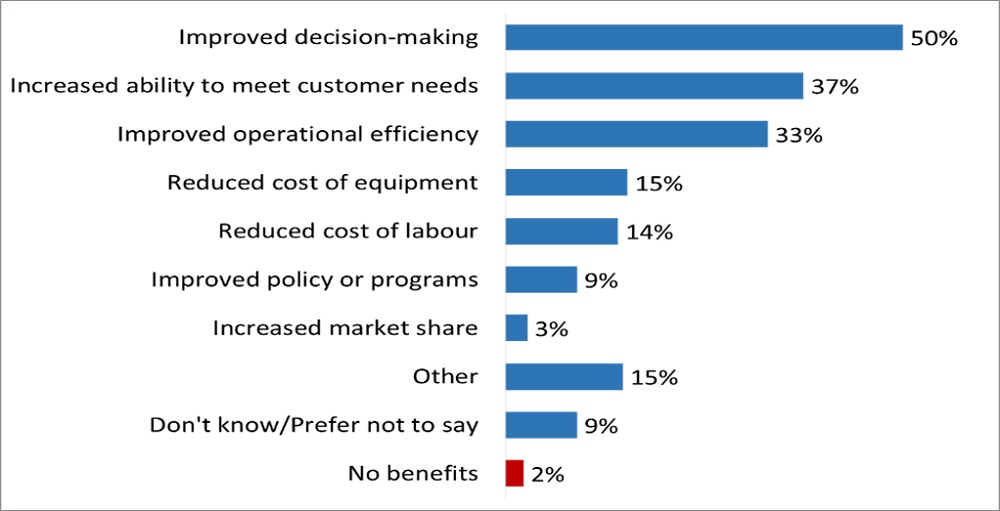

Survey, interview and document evidence, which includes CCMEO’s Economic Value Study and Environmental Scan of the geospatial sector, suggests that there is a plausible link between Essential Geographic Information sub-program and broader economic benefits. Moreover, users of geospatial information and geodetic services most frequently reported operational efficiencies and other productivity benefits. Other international economic studies have also provided support for the contribution of open geospatial information and geodetic services to broader economic benefits.

Evaluation Findings: Performance (Efficiency and Economy)

The sub-program uses credible information for their planning and priority-setting processes. CCMEO engaged in broad consultation processes which resulted in the National Mapping Strategy and a six-point action plan focussed on collaborative governance. However, document and interview evidence indicate that there are some gaps in information for GeoBase and remote sensing science programs regarding user needs and federal horizontal priorities. CGS has used environmental scans and needs assessment information in their planning processes, but requires more formal links to academia, a key user group for their services. CCOG was noted to be an effective FPT working group, but was viewed by NRCan interviewees as providing insufficient provincial/territorial strategic input into the sub-program’s planning processes.

CCMEO and the CGS have both had budget reductions during this evaluation period (50% and 25% respectively). This reduction is also reflected in the number of Full Time Equivalents engaged, a 45% reduction in CCMEO from 360 in 2010-11 to 199 in 2014-15, and a 20% reduction in CGS from 45 in 2010 to 36 in 2014-15. However, available performance and financial information are not sufficient to quantitatively assess the impact of these budget reductions on program delivery and efficiency or the extent to which products or services may have declined in terms of quality or quantity. Nevertheless most provincial, federal and international interviewees point to a decline in sub-program capacity. A common theme reflected in interviews and document evidence is a lack of awareness among key government decision-makers as to the importance of geodesy and geospatial information resulting in the perceived under resourcing of these programs.

Most federal and provincial interviewees indicated that there were insufficient resources to adequately update GeoBase. However, GeoBase sustainability issues were also attributed to delivery issues such as governance; competing federal, provincial, territorial priorities; insufficient provincial capacity to provide data in the required format; slow government adoption of advanced technologies for efficient data management and storage; the need for enhanced alignment of outputs to strategic priorities and user needs; and possible program design issues related to the precise role of the federal government in providing data, and the identification of appropriate target groups for geospatial products.

Questions around the sustainability of GeoBase indicate that while inadequate resources have been identified as an issue among key stakeholders and partners, there is a need to explore viable delivery and partnership approaches through broad consultation and a review of best practices in other jurisdictions. Through a related CCMEO program, GeoConnections, various studies and some promising pilot projects have been undertaken with a view to improving the viability of its data infrastructure, which includes GeoBase framework data. Whether these pilot projects have further potential or whether new studies are required may warrant additional examination. As well, the Federal Geospatial Platform (FGP), delivered by CCMEO, aims to manage federal geospatial information in a more efficient and coordinated way by using a common platform of technical infrastructure, polices, standards and governance which aims to improve access, reusability and reduce duplication.

Strategic planning and coordination with respect to satellite infrastructure, remote sensing science and GeoBase were noted by internal and external interviewees to be constrained by the absence of updated legislation and a horizontal policy framework relating to geomatics. Document and interview evidence also noted challenges in long-term planning and sustaining remote sensing science efforts to efficiently generate products given its reliance on unstable external funding. Document and interview evidence also suggest the need for stronger ongoing connections between the sub-program and its user base to ensure adequate understanding of user needs and emerging geomatics practices and trends. Several interviewees suggested the establishment of an Industry or User Advisory Committee linked to key coordinating bodies such as FCGEO, CCOG and FGCB. While a multi-stakeholder group, GeoAlliance, exists, interviewees expressed concern about the current capacity of this group.

Performance information is inconsistently tracked across the sub- program components. CCMEO lacks an overall performance measurement strategy for its programs and services and various outputs and outcomes are inconsistently reported across CCMEO programs. CGS has an existing performance measurement strategy, but needs to better track and report on its outcomes (e.g. impact of use on organizations).

Based on the findings and conclusions of the evaluation, the following recommendations are made to the Assistant Deputy Ministers of the Strategic Policy and Results Sector (SPRS) and of the Lands and Minerals Sector:

- Recommendation 1: CCMEO should update its business analysis in order to

- clarify the current needs of user groups and stakeholders and future directions of geospatial information (e.g. GeoBase) and remote sensing science;

- strengthen governance; and

- establish more viable approaches to sustain and update core geospatial data (GeoBase) and to sustain remote sensing science.

- Recommendation 2: CCMEO and CGS should strengthen linkages with appropriate stakeholder and user groups in order to stay abreast of user needs and emerging trends. For the CCMEO Branch this means stronger and sustained linkages with the private sector (with respect to geospatial programming) academia, and possibly emerging user groups. For the CGS this means strengthened linkages with academia, and more sustained linkages to users (e.g. through the Federal GNSS Coordination Board).

- Recommendation 3: CGS should develop a plan with other federal government partners to analyze gaps and identify options to mitigate infrastructure deficiencies in Canada’s geodetic observing infrastructure that are impacting negatively on Canada’s international commitments.

- Recommendation 4: CCMEO and CGS should improve accessibility and user support for geodetic and geospatial services and tools. CCMEO, in consultation with Shared Services Canada, should ensure that the new system to archive remote sensing imagery is adequately accessible. For CGS, SGB this means enhancements to user support materials particularly the Canadian Spatial Reference System Precise Point Positioning Service.

- Recommendation 5: CCMEO and CGS should improve performance measurement and reporting to ensure adequate information is available to assess efficiency and effectiveness. For CCMEO this means the development and implementation of a performance measurement strategy and regular program reporting of key outputs and outcomes (in addition to Departmental Performance Reporting). For CGS, this means an enhancement of their existing strategy to ensure better monitoring and reporting of outcomes related to the impacts of use of geodetic services.

- Recommendation 6: CCMEO and CGS should develop and implement a strategy to communicate the value and benefits of geodetic services and geospatial information to stakeholders and key decision-makers.

The recommendations and management responses are contained in Section 4 of this report.

1.0 Introduction and Background

1.1 Introduction

The evaluation assesses the issues of relevance and performance (effectiveness, efficiency and economy) of Natural Resources Canada’s (NRCan’s) Essential Geographic Information Sub-Program (3.2.1). The evaluation questions and methods (including the associated level of effort) were informed using a risk-based approach.

The evaluation covers the five year period from 2010-11 to 2014-15 and approximately $171 million in NRCan’s expenditures. The Essential Geographic Information Sub-program is delivered by two branches within the Earth Sciences Sector: The Canada Centre for Mapping and Earth Observation (CCMEO) and the Surveyor General Branch (SGB). The sub-program includes four Divisions:

- GeoBase Division, CCMEO

- Canada Centre for Remote Sensing (CCRS), CCMEO

- Canadian Geospatial Data Infrastructure (CGDI), CCMEO

- Canadian Geodetic Survey (CGS), SGB

1.2 Sub-Program Activities and Key Outputs

The Sub-program delivers foundational data and services including authoritative mapping, satellite imagery, remote sensing science technologies, an accurate and consistent system of geographic coordinates (longitude, latitude, height and gravity) and tools to access this data. It supports the development of technologies, methods and tools to improve geospatial and geodetic data access and quality. It is also responsible for managing satellite ground infrastructure (i.e. antennas) and geodetic observing infrastructure (e.g. GPS satellite receiver stations) to support the production of information. The sub-program provides leadership and coordination support to various national and international committees and activities relating to geodesy, and other earth observation and geospatial activities such as the Federal Committee on Geomatics and Earth Observation, the Canadian Council on Geomatics, the United Nations Committee of Experts on Global Geospatial Information management, the United States Geological Survey and the International GNSS Service.

The following describes the programs, services, tools, and data that are part of this sub-program:

-

GeoBase provides national geospatial information and data. Geospatial information identifies and describes the geographic location of features and boundaries. Geospatial products and services are available online through the GeoGratis platform which contains numerous data products such as interactive maps, Canadian Geographic Names database, Atlas of Canada, Canada Lands Index Maps, and satellite imagery. In addition to geospatial data, the GeoGratis platform includes web services which enable developers to build value-added data products. GeoGratis is also a key online access point for GeoBase Federal-Provincial-Territorial (FPT) framework data that consists of 26 data layers such as the national road, and hydro networks, Indigenous lands, administrative boundaries, elevation information, and land cover. It should be noted that products discoverable through the GeoGratis web site have been migrated to the Government of Canada’s Open Government Portal to comply with the Directive on Open Government (Section 6.2) effective April 2017. The GeoBase Division also provides mapping and geospatial expertise and information for federal government programs and international initiatives, treaties and agreements (e.g. cross boundary initiatives, North American energy infrastructure mapping).

Framework data are supplied by federal and provincial mapping agencies, municipalities and commercial data suppliers in Canada. While GeoBase framework data were previously accessible through a separate web portal, the portal was closed in January 2015 and GeoBase framework data were moved to the GeoGratis web platform. As of 2017 this data has migrated to the Government of Canada’s Open Data Portal and the Federal Geospatial Platform. The renewed GeoBase 2 Strategy is intended to harmonize the FPT GeoBase Initiative with the FGP initiative.

- Remote sensing science primarily involves in-house research and development (R&D) activities focused on development and improvement of earth observation technology, applications and data to facilitate use by government researchers and decision-makers. These technologies are related to various remote sensing techniques such as radar, optical, and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (AUV). Activities for CCRS during the evaluation period included preparing federal government stakeholders for use of new remote sensing data from existing and new satellite missions such as the upcoming RADARSAT Constellation Mission (RCM)Footnote 3; developing targeted remote sensing operational applications for the RCM and for key natural resources (oil sands, the North).Footnote 4 Long-term Satellite Data Records (LTSDRs), produced by CCRS, are combined satellite images generated from four optical sensors/satellitesFootnote 5 to create national scale images of Canada that span decades.Footnote 6 The CCRS also provides emergency geomatics services which provides enhanced satellite imagery and expertise, mostly in response to flooding events for federal, provincial and international governments. Remote sensing science and expertise is delivered by the Canada Centre for Remote Sensing (CCRS), CCMEO.

- Operation and revitalization of satellite ground infrastructure are key activities within this sub-program. Satellite ground Infrastructure monitors and controls satellites, and receives, processes and distributes satellite data.Footnote 7 NRCan has satellite ground stations at: Prince Albert, Saskatchewan (established in 1972); Gatineau, Quebec (established in 1986); and Inuvik, Northwest Territories (established in 2010). The Inuvik ground station has one antennae owned by the Canadian government and as of 2016 it was hosting three other satellite antennas (owned respectively by the German Aerospace Centre, the Swedish Space Corporation and one partly owned by the French Centre - national d’études spatiales). Between 2012-13 and 2014-15, a project was undertaken to revitalize the aging ground infrastructure and included the replacement of antennas, and the installation of an additional antenna at the Inuvik Satellite Station Facility.Footnote 8 The Canadian Geospatial Data Infrastructure Division is responsible for managing Canada’s satellite ground infrastructure.Footnote 9

- Remote sensing imagery products are acquired, managed and archived through the National Earth Observation Data Framework (NEODF)Footnote 10 Catalogue. This system is being replaced with the Earth Observation Data Management System (EODMS), to be operated by Shared Services Canada. The NEODF catalogue archives and provides access to satellite data and consists of RADARSAT 1 and -2 satellite data from other satellites obtained through the National Master Standing Offer (NMSO).Footnote 11 The catalogue houses about 112,000 images and long term satellite data records (LTSDRs).Footnote 12 Although the catalogue is an open access system, RADARSAT-2 images can only be shared without costs amongst Government of Canada users and cannot be accessed by the public free of charge.Footnote 13

- The Canadian Spatial Reference System (CSRS) serves as a national standard for spatial positioning in CanadaFootnote 14 and provides the coordinates for Canada’s positioning (longitude, latitude, height, gravity). It is the basis for all mapping, navigation, boundary demarcation, and measuring changes to the earth’s crust.Footnote 15 Given continuous earth movements and shifts, ongoing geodesy work is needed to ensure continued accuracy of spatial coordinates. The CGS maintains the reference system and provides various geodetic services, tools, data and infrastructure to ensure efficient access to standardized position coordinates, including:

- Canadian Active Controls System (CACS)Footnote 16 is a network of navigation satellite tracking stations that provides GNSS coordinates- Canada does not have its own navigational satellites and primarily tracks the American Global Positioning System (GPS) satellites through this system.

- Canadian Spatial Reference System - Precise Point Positioning (CSRS-PPP) service is a positioning technique that results in a high level of position accuracy with no base station required.Footnote 17 This service allows users (primarily surveyors, engineers and researchers), to obtain corrected, more accurate GNSS coordinatesFootnote 18 in a national standardized format.

- Canadian Base Network (CBN) is a network of ground-based pillar monumentsFootnote 19, maintained by CGS, that are tied directly to the CACS stations and supporting the Canadian Spatial Reference System.Footnote 20 It also provides anchor points for the integration of denser, provincial networks of monuments. These provincial networks are relied upon by provinces for position coordinates, particularly in urban areas. The aim is to eventually phase out the provincial system of monuments for space-based technology.

- Canadian Gravity Standardization Network, consistent with international gravity standards, of which CGS maintains the national primary gravity reference network (consisting of approximately 70 stationsFootnote 21) to provide accurate gravity values.

Other Interdependent CCMEO Programs

While these programs are not within the scope of this evaluation, they are highly interdependent with other CCMEO programs within the Essential Geographic Information sub-program and so are worth mentioning. The GeoConnections program is a national initiative, led by CCMEO, designed to facilitate open access to and use of authoritative geospatial information in Canada through coordination and leadership and support for the advancement of framework data, policies, standards, and technologies (Canadian Geospatial Data Infrastructure, CGDI) needed to make geospatial information more accessible and compatible with other information. Through GeoConnections, CCMEO plays a leadership role in the long-term sustainability of the CGDI. This program is also intended to support technology and data integration innovation.

The Federal Geospatial Platform (FGP) is an initiative of the Federal Committee on Geomatics and Earth Observations and was designed to manage federal geospatial information in a more efficient and coordinated way by using a common platform of technical infrastructure, polices, standards and governance to improve access, reusability and to reduce duplication. Responsibility for the development and delivery of the FGP rests with CCMEO. The Branch also provides broad horizontal leadership and coordination support for this initiative. The FGP products and services can be accessed through the Open Government Portal or through an internal government network. The GeoBase 2.0 Strategy is intended to harmonize GeoBase with the FGP initiative by linking more widely available federal geospatial data with geospatial data from provinces and territories. Once the FGP initiative is completed, management of the platform will be assumed by the GeoBase Division.

1.3 Context

Geographically, Canada is the second largest country in the world and has the world's longest coastline with the majority of its land mass scarcely populated and difficult to access. This means that with scarce resources it is challenging to adequately map, monitor and provide precise location services, particularly in the rural, remote and northern regions of Canada.

Rapid technological changes have substantially changed the earth observation and mapping playing field. This rapid pace is ongoing and has quickened to the point where the geospatial innovation cycle results in new products and service lines approximately every two years.Footnote 22 The move to space-based technologies (satellites) and Geographic Information Systems (GIS), a method of managing, analyzing and displaying geographic information and tools, have allowed geospatial activities to become mainstream. The integration of space-based navigation technology into portable devices such as smartphones means that geospatial technology and information is ubiquitous. The role of the private sector and local governments in collecting and providing geographic information and services has increased significantly. For example, Google has become a large provider of spatial information to citizens and initiatives such as Open Street Map, a community mapping effort, are becoming increasingly popular.Footnote 23 Within the federal government there has also been a significant diversification of earth observation data and the departments and agencies that produce the data.

Another trendFootnote 24 that has implications for the management of space and satellite infrastructure programs is the growing number of small satellites, which shorten the development time of the satellites, reduce the costs of satellites and facilitate the accessibility of earth observation data. This means that government funding and procurement practices may have to align with the style of proposal and system development best suited for small satellite missions.Footnote 25

Decentralization and the proliferation of stakeholders involved in the production of geospatial data has resulted in changing business models for service delivery within the private and public sectors.Footnote 26Footnote 27 Globally, and in Canada, collaborative forms of governance have evolved in an effort to pool data assets and to enhance efficiencies. It is predicted that, increasingly, geospatial information, resources and applications will be built collaboratively, using open, rapid deployment strategies and open standards.Footnote 28

There has also been an increase of national and regional government open data policies in Canada and internationally. Canada’s Action Plan on Open Government and the Directive on Open Government, which support the Policy on Information Management, came into effect in 2014, and aims to optimize the release of government information and data of business value to support transparency and accountability.Footnote 29 Most information has a geospatial component and therefore this policy has important implications for the accessibility of geospatial information. The Government of Canada has an open data portal, much of which contains geospatial data from Natural Resources Canada.Footnote 30

1.4 Expected Results

As outlined in NRCan’s Performance Measurement Framework (PMF) the expected result for the Essential Geographic Information is as follows:

- Public, private sector and academia access authoritative, reliable and accurate geodetic, geographic and geospatial information for the management of natural resources and lands.

In the absence of a logic model for the sub-program and in consultation with the Evaluation Advisory Committee, the Evaluation team developed a results chain to identify expected results.Footnote 31 The Sub-program’s effectiveness is assessed against these results which relate to access and use of the information, services, infrastructure, technologies and products:

- Enhanced access and use of sub-program information, technologies, infrastructure and services;

- Benefits of use (improved decisions, enhanced programs, policies, research; increased operational efficiency and productivity); and

- Net benefits to Canadians (e.g. economy, environment).

1.5 Resources

NRCan expended approximately $171M in operations and maintenance (O&M) funds, salary and Employee Benefits Plan (EBP) from 2010-11 to 2014-15. External sources of funds (from other government departments and provincial/territorial governments) totalled approximately $15M. In addition, $41.6 million of C-based funds were utilized for the revitalization of ground satellite infrastructure from 2012-13 to 2014-15. It should also be noted that for GGDI sources of funds for ground segment operations, archives and access also include cost recovery through the Geomatics Canada Revolving Fund (GCRF). On average, from 2010-11 to 2014-15 earth observation programming has received approximately $2M (in O&M and salaries) annually from the GCRF. Table 1 shows the planned and actual expenditures for the sub-program from 2010-11 to 2014-15.

Table 1: 3.2.1 Sub-Program Estimated Planned and Actual Expenditures by Branch Level ($000s)

Source: Expenditure information provided by CCMEO and CGS program representatives

Text version: Table 1

Table 1 provides planned and actual expenditures for the Canadian Centre of Mapping and Earth Observation (CCMEO) and the Canadian Geodetic Survey (CGS) from fiscal years 2010-11 to 2014-15. Total actual expenditures for the sub-program were $186,074,000. Total actual expenditures (2010-11 to 2014-15) for CCMEO were $170,987,000 and for CGS were $15,087,000.

1.6 Governance

The CCMEO is responsible for remote sensing, mapping, and geospatial data management and infrastructure functions previously held in three separate branches of the previous Earth Science SectorFootnote 32: Canada Centre for Remote Sensing; the Mapping Services Branch; and the Data Management and Dissemination Branch).

The Canadian Geodetic Survey (CGS), Surveyor General Branch has a mandate to establish and maintain a geodetic reference or coordinate system as a national standard for spatial positioning throughout Canada that is consistent with international standards.Footnote 33 The CGS transitioned from Canada Centre for Remote Sensing to the Surveyor General Branch in 2013.Footnote 34 The sub-program operates within a collaborative environment and plays a key role in various national and international committees and collaborative activities to support accurate and consistent data and information.

CCMEO has moved towards a more cooperative approach to facilitate the management of geospatial information in Canada and delivers core horizontal, national policy frameworks. The GeoBase Initiative is a Federal-Provincial-Territorial (FPT) undertaking that is overseen by the Canadian Council on Geomatics (CCOG) and supported through cost-shared and data-sharing agreements between CCOG members. CCMEO has key delivery accountability for GeoBase production and stewardship of core FPT data. The GeoBase Steering Committee, comprised of FPT representatives, makes recommendations to the CCOG who in turn makes recommendations to the GeoBase division (CCMEO). The CCOG is the main decision-making body for the GeoBase Initiative.Footnote 35 GeoBase 2.0 represents a commitment towards a new collaborative model and is intended to support the evolution from data producer to data integrator.Footnote 36

The creation of GeoBase began in 2001 following the release of a reportFootnote 37 that identified that basic geographic information in Canada was in danger of becoming irrelevant unless significant investment was made at all levels of government. GeoBase was formed as a joint initiative with the intent of having federal, provincial and territorial governments work cooperatively to ensure the provision of, and access to, a common up-to-date and well-maintained base of quality geospatial information covering the entire Canadian landmass.

Table 2 depicts many of the key coordinating bodies that are relevant to each Division. Typically multiple governance bodies guide the work of each division.

| Coordinating and Consultation Bodies | Division | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGDI -satellite ground infrastructure | CCRS | GeoBase Division | CGS | |

| Canadian Council on Geomatics (CCOG) | X | X | X | |

| GeoBase Steering Committee (sub-group of CCOG) | X | |||

| Canadian Geodetic Reference System Committee (sub-group of CCOG) | X | |||

| Federal Committee on Geomatics and Earth Observation (FCGEO) | X | X | X | |

| GeoAlliance Canada (external multi-stakeholder group) | X | |||

| Federal GNSS Coordination Board (FGCB) | X | |||

| Geographical Names Board of Canada | X | |||

| Space Advisory Board and other space program committees and boards led by Canada Space Agency | X | X | ||

| Director General Emergency Policy Committee / Director General Events Response Committee | X | |||

| United Nations Committee of Experts on Global Geospatial Information Management (UN-GGIM) | X | X | X | X |

| (International) Committee On Earth Observation Satellites (CEOS) | X | X | ||

| Arctic Spatial Data Infrastructure Board of Directors | X | |||

| International Committee on Global Navigation Satellite Systems (ICG) | X | |||

| International GNSS Service (IGS) | X | |||

The CCOG constitutes the major FPT governance body for geospatial information. NRCan is the lead federal representative at CCOG and houses the CCOG Secretariat. The CCOG aims to provide a forum for exchanging information on programs, consider common operational issues, discuss proposed legislation relevant to geomatics (particularly land surveying), and develop and promote national geomatics standards.Footnote 38 A number of working groups and committees report to the CCOG such as the GeoBase Steering Committee; the Canadian Geodetic Reference System Committee (CGRSC) and the Imagery Working Group.Footnote 39

While the CGRSC reports to CCOG, geodetic expertise resides with the CGRSC. The CGRSC is responsible for planning and coordinating inter-agency work to maintain and improve the Geodetic Reference System in Canada as a standard for positioning of geographically referenced information related to the Canadian landmass and territorial waters.Footnote 40 NRCan’s Geodetic Survey Division takes a leadership role in this committee, providing the Chairperson and the Secretary.

The Federal Committee on Geomatics and Earth Observations (FCGEO) was created in January 2012. It has 21 federal department and agency members that produce or use geospatial information, or have an interest in related issues. The FCGEO’s ADM-level steering committee is supported by a Director General-level shadow committee, Director-level working groups, and is co-chaired by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) and NRCan.Footnote 41 The FCGEO is intended to enhance federal geomatics and earth observation infrastructure and improve access, sharing and integration of geospatial data at all government levels.Footnote 42 Key activities related to geospatial information include: providing whole-of-government leadership in establishing priorities for geomatics and earth observation; preparing coordinated federal positions, serving as the collective federal voice, developing standards, and guidelines, strengthening federal capacity, and seeking efficiencies across federal government departments and agencies.

The Geographic Names Board of Canada (GNBC) is Canada’s national coordinating body responsible for standards and policies on place names. It comprises FPT government representatives with specific authority and responsibility for their respective jurisdictions. GNBC members coordinate efforts to ensure that geographical names are consistently managed. NRCan chairs this Board and provides the Secretariat (situated within CGDI) as mandated by an Order-in-Council.

The key federal coordination body for the CGS is the Federal Global Navigation Satellite Systems Coordination Board (FGCB)Footnote 43: This Board advises and coordinates federal government departments and agencies in matters related to global navigation satellite infrastructure development, implementation and use.Footnote 44 The Director General of the SGB chairs the FGCB.

The Canadian Space Advisory Board and other Canada Space Agency (CSA) space program committees, boards and working groups: these entities, led by CSA and made up of a number of participants, including NRCan, provide strategic advice on space, coordinate federal government priorities in space to ensure effective resource use, and provide advice on policy and user needs and priorities.Footnote 45 The CCRS participates in a number of CSA working groups. Both CCRS and CGDI have MOUs with CSA relating to ground satellite infrastructure, remote sensing science (pertaining primarily to radar satellite applications and missions), and archiving and cataloguing of satellite imagery. Under agreements pertaining to remote sensing science, CCRS conducted research that was partly supported by CSA’s Government Related Initiatives Program (GRIP) funding and other NRCan program sources such as Geo-Mapping for Energy and Minerals.

2.0 Evaluation Approach and Methodology

2.1 Approach – Contribution Analysis

The evaluation used a contribution analysis approach which assesses the contribution made by a policy or program to the observed results in the context of other influencing factors. This is consistent with Treasury Board Secretariat guidance for evaluating complex programs such as Essential Geographic Information.Footnote 46 Given the governance and delivery complexity of this sub-program this approach was deemed a suitable analytic method.

Contribution analysis does not attempt to prove that one factor – a policy or program – ‘caused’ the desired outcome. Instead, this approach explores the contribution made by a policy or program to the observed results. To do this, a results chain was developed, based on input from CCMEO and SGB staff that articulated the ‘theory of change’ showing the links between program activities, outcomes and contexts. Evidence was collected to test the validity of the results chain and support the construction of a credible performance story to demonstrate the extent to which the program was an important influencing factor in driving the observed change.

2.2 Methodology

The Evaluation of the Essential Geographic Sub-Program employed a multiple lines of evidence approachFootnote 47 which consisted of:

- Document and literature review: An overall review of key program and performance, planning and reporting documents was conducted. In addition, a review of governance, organizational structures and delivery mechanisms in other jurisdictions was conducted (United Kingdom, European Union, United States, and Australia).

- Interviews: A total of 95 individuals were interviewed from May to September 2016. This does not include the 15 additional interviews that were conducted as part of the case studies. Interviewees were distributed among the following groups:

- Essential Geographic Information senior and program managers and employees: n=16

- Federal partners and end-users: n=34

- Provincial and territorial stakeholders and end-users: n=13

- Private Sector: n=17

- International: n=10

- Academia: n=3

- Municipal government: n=2

-

Case studies (3): The following three program areas were explored through case studies:

- long term satellite data records;

- revitalization of satellite ground infrastructure project, and

- Canada’s contribution to the Global Geodetic Reference Frame.

Document reviews and a total of 15 additional interviews were conducted, primarily consisting of external stakeholders and end-users. The case studies were selected based on various criteria such as inclusion of activities occurring in high priority areas. Interviews for the case studies were conducted from May to August 2016.

-

Online Surveys (5) of end-users and CCOG committee members:

Four online user surveys and one online survey of CCOG members were conducted from August to October 2016:

- Two online user surveys of two geodetic services/products: CSRS -Precise Point Positioning (57 respondents contacted via email and web interceptFootnote 48) and GPS-Height tool (13 respondents contacted via web intercept);

- Two online user surveys that included -GeoGratis and GeoBase information (552 respondentsFootnote 49 contacted via web intercept, of which 177 were categorized as professional users and the focus of the evaluation’s analysis)); and an online user survey related to the GeoGratis application programming interface (66 respondents contacted via web intercept and email);

- One online census survey of members of the CCCOG and three of its committees: the GeoBase Steering Committee; National Imagery Working Group; and Canadian Geodetic Reference System Committee. In total, 20 out of 35 invited committee members responded to the survey.

For each evaluation issue, a rating and summary of the supporting evidence are provided. The rating statements outlined in Table 3 assisted in ensuring consistency in reporting and facilitating the interpretation of qualitative data. Please note that these ratings are applied to the sub-program rather than individual programs.

| Statement | Definition |

|---|---|

| Demonstrated | Intended outcomes or goals were achieved or met. |

| Partially Demonstrated | Considerable progress was made to meet intended goals, and achievement is expected based on current plan. |

| Partially Demonstrated – Action Required | Some progress has been made to meet the intended outcomes or goals. Management attention is needed to fully achieve desired objective or result. |

| Not Demonstrated | Limited or no progress has been made to meet the intended outcomes or goals as stated, or the outcome is no longer applicable (due to changes in the external environment). |

2.3 Evaluation Limitations

Four key evaluation limitations and mitigation strategies are discussed below:

- Program complexity and attribution: Attribution is challenging given the myriad of influencing factors on results. It is difficult to isolate the impact of various activities conducted by NRCan that were not within the scope of this evaluation. For example, it is difficult to isolate the impacts of the sub-program from other interconnected programs such as GeoConnections and the Federal Geospatial Platform. While the evaluation design cannot fully resolve this issue, it was mitigated through the use of the contribution analysis approach, which assessed how internal factors (those within the control of NRCan) and external factors have influenced outcomes along a results chain.

- Challenges reaching all end-user groups: Certain stakeholder groups proved harder to reach than others, particularly academic representatives. A larger sample of academic representatives was collected and contacted, but the response rate for this group remained low. The document review was broadened to review academic perspectives pertaining to earth observation, geomatics, remote sensing and geodesy to mitigate this limitation.

- Representativeness of survey samples: The samples for the user surveys cannot be assumed to be representative of each respective user population.Footnote 50 To mitigate this limitation, survey information has been analyzed in conjunction with other lines of evidence.

- Measuring the efficiency of public sector program using quantitative measures: Public sector outputs are difficult to define and value making it difficult to develop valid efficiency measures. The literature on public sector efficiency metrics also highlights contradictions as to how efficiency and productivity should be defined. As well, there is insufficient expenditure information related to specific outputs as well as specific inputs associated with an activity or output. Even if this quantitative data existed, sole reliance on this data such as cost per output masks the complexity of efficiency and can create perverse incentives, such as a reduction in quality in order to reduce costs. The evaluation analyzed efficiency primarily through an assessment of key delivery issues related to planning, governance, implementation, data quality, and performance measurement.

3.0 Evaluation Findings: Relevance – Demonstrated

Summary:

There is an ongoing need for the sub-program because location-based information is critical for assessing, understanding and managing issues relevant to national priorities such as climate change, natural and human-made hazards, natural resources, public safety and security; and sustainability of lands at regional to global scales. Precise and reliable geodetic coordinates are needed for navigation, land surveying, engineering, and geoscience. Open access to geospatial information is recognized by Canadian and international governments as an important driver for innovation and the economy.

There continues to be a role for the federal government and NRCan for providing leadership and coordination support; and for ensuring data quality and accessibility and national coverage of mapping, earth observation assets, geospatial and geodetic services and information. The federal government should continue to provide critical and trusted national datasets, such as GeoBase framework data, although the precise nature of this role requires further clarification.

3.1 Ongoing Need - Demonstrated

There is an ongoing need for reliable and accurate national geospatial and geodetic information to better assess, understand and manage issues relevant to national priorities

According to interview and documentFootnote 51 evidence, there is an increasing demand for national geospatial information and precise spatial coordinate data for a broad range of applications. This information is considered by NRCan and external interviewees as critical for informing issues relevant to national priorities. With technological advances that enhance data quality and accessibility, national geospatial datasets, remote sensing imagery and applications, and geodetic coordinate data have become increasingly valuable for assessing, understanding and managing important national issues such as those related to the environment, natural and human-made hazards; public safety, sovereignty, natural resources, transportation, economic competitiveness and sustainable development.Footnote 52 As well, there are emerging uses for geospatial information such as the ‘Blue Economy’ (i.e. ocean) and green energy.Footnote 53

Of particular note is the value of geospatial and earth observation information and technology for research. Interviews with researchers and various reportsFootnote 54 highlight the importance of geospatial data and technologies for research in various areas such as biodiversity, forestry, watershed analysis, and the assessment of climate change impacts. Geospatial information can be used to examine environmental changes at both global and national scales.Footnote 55 In addition, remote sensing data can provide observations of land cover consistently over time to monitor earth’s changes, including the impact of climate change on the earth’s surface.Footnote 56

As well, accurate position coordinates, earth observation data and associated satellite ground infrastructure can play an important role in northern development by permitting safer navigation through the northern sea and air routes and support delivery of services to northern communities.Footnote 57

Canada’s geodetic reference system (or coordinate system) is the foundation for other geospatial information and a multitude of activities that require highly accurate positioning.Footnote 58 Precise and reliable location coordinates, are neededFootnote 59Footnote 60 for specific applications such as land surveying, engineering, monitoring earthquakes, charting flood plains, glaciology, and accurate guidance for remotely operated machinery (such as those currently used in the agricultural sector).Footnote 61 Geodesy is considered a fundamental element of work by provincial/territorial stakeholders (e.g. land title registry).Footnote 62 The CSRS- Precise Point Positioning service, offered by CGS, was considered by external stakeholders and users consulted to be useful for obtaining accurate position information in Northern or remote regions of Canada where users are some distance away from GNSS or other location services.

Various national and international organizationsFootnote 63 cite the need to have a current, accurate, complete national base data by several sectors of the economy to build other data layers upon (the key premise of GeoBase).Footnote 64 Federal and provincial stakeholders consulted consider location-based information to be a vital component of effective decision-making.Footnote 65 Various reports have estimated that a large portion of business and government decisions has a geospatial component.Footnote 66 Linking spatial information to socioeconomic or environmental information, leads to a comprehensive understanding of these issues.

Numerous studiesFootnote 67, including the Canadian Geomatics Environmental Scan and Value Study, indicate that accessible geospatial and geodetic information is an important economic driver. This information is reported to be important for increasing productivity, making strategic decisions, and reducing the costs of doing business. Moreover, direct financial gains are possible from the sales of new products and services in which geospatial and geodetic information is a component. Various jurisdictions, including Canada,Footnote 68 have documented that accessible geospatial/geodetic data facilitates innovation by reducing cost and information barriers.

3.2 Role of Federal Government and Natural Resources Canada - Demonstrated

The role of the federal government is legitimate and viewed as appropriate for ensuring national coverage, consistency, accuracy of and access to geodetic coordinates and geospatial information

Both the Natural Resources Act and the Resources and Technical Surveys Act provide NRCan with a broad mandate with respect to mapping, remote sensing and technical surveying. In the area of emergency response, NRCan has mandated responsibilities for geomatics.Footnote 69 The Canadian Geomatics Accord, originally signed in 2002 and renewed recently in 2014, is the framework that allows federal, provincial and territorial government agencies to collaborate and provide support for geomatics initiatives. However, there is no legislative framework for geomatics, spatial data infrastructure and related geospatial networks, coordinating bodies, and committees.Footnote 70

The CGS has a specific mandate which responds to the 1909 Order-in-Council responsible for its creation “to determine with the highest attainable accuracy the position of points throughout the country…” It does this by delivering the Canadian Spatial Reference System and contributing to the global reference system.

The federal role in supporting geospatial and geodetic programs is viewed by federal, provincial and international interviewees as critical for planning and management of cross jurisdictional issues such as pandemics, economic issues, watershed analysis, demarcation of jurisdictional boundaries, and monitoring climate change.Footnote 71

According to NRCan and external stakeholders consulted, there continues to be an important role for the federal government and NRCan in the following areas:

- national and international leadership and coordination support role to ensure harmonization and consistency, and to increase efficiency, information sharing and the capacity to address cross jurisdictional issues;

- ensuring consistency, accuracy of and access to geodetic services and geospatial information; and

- ensuring national coverage of mapping and earth observation assets, geodetic services and data particularly in the North and remote areas, where private sector is less likely to be involved.

Globally, and in CanadaFootnote 72, there is a recognized need for national governments to organize and coordinate the collection and management of geospatial data given the increase in data production. It is recognized that “collecting data multiple times for the same purpose is wasteful and inefficient… Alternatively geospatial data could be collected once to meet the requirements of several users.”Footnote 73 Federal and international stakeholders consulted view cooperation and collaboration as critical for ensuring consistency and harmonization of mapping, geospatial information and geodetic coordinates across jurisdictions.

Stakeholders consulted viewed the role of the federal government as important for providing geodetic, earth observation and geospatial services and data where there are gaps in coverage as is the case in the North and other remote areas. Interviewees noted in some cases that there was insufficient provincial or territorial capacity to provide adequate geospatial and geodetic services. Territorial representatives indicated that given capacity issues, national geospatial information and geodetic services is critical to their work. Private sector interviewees generally indicated that there is less likely to be a sufficient business case for providing data or services in more remote areas of Canada.

While other stakeholders provide GNSS coordinate data and services, provincial, federal and international interviewees agreed that CGS has a clear and appropriate role in providing authoritative and precise coordinate data within a standardized format for the following reasons:

- it is critical spatial data that supports national interests such as sovereignty;

- it enables consistent GNSS coverage throughout Canada;

- external stakeholders views the federal geodetic services as important for verifying GNSS technology and spatial coordinates; and

- it ensures standardized spatial coordinates across jurisdictions.

Federal and external stakeholder interviewees agreed that federal support for critical national data layers, such as GeoBase framework data, was appropriate, although the precise nature of this role was a subject of debate among interviewees and in the literatureFootnote 74. Some external interviewees suggested that NRCan should transition from role of data providerFootnote 75 to one of data verifier. A few external stakeholders questioned the federal government’s role in providing national data layers such as those relating to road networks given numerous mass market tools that currently provide road data. Other NRCan and external interviewees viewed the federal data provider role as appropriate for the following reasons: it provides assurance that data is authoritative; national core datasets are viewed by many as critical infrastructure; and, the federal government, and NRCan specifically is well positioned to collect and integrate provincial, territorial and other sources of geospatial data.

Archiving of geospatial information is generally viewed as an appropriate role for the federal government because it is a critical source of information for research and archiving would likely not be done by others

Federal researchers and academic interviewees noted that the federal government has a critical role to play with respect to the archiving of national geospatial information. Federal and external interviewees frequently cited the importance of the federal role in preserving digital data, including geospatial data, and to ensure it is accessible. External stakeholders indicated that this role would not likely be taken up by regional governments or the private sector.Footnote 76

Remote sensing research conducted by CCRS provides continuity of expertise and is considered appropriate for supporting national priorities and technology transfer to federal government stakeholders

Federal interviewees considered that the advantage of CCRS remote sensing research, as compared to academic research, was the continuity of expertise which helped to support government policy and program decision-making with respect to federal priorities. Government remote sensing research was considered less appropriate by federal and other stakeholders in areas where private sector involvement is more likely (e.g. mineral exploration, oil sands).

Federal support for satellite ground infrastructure is viewed as appropriate to protect critical infrastructure and to provide government with secure, consistent access to satellite data

Federal funding for satellite ground infrastructure was considered necessary by interviewees for providing government with secure, consistent access to satellite data used to support national priorities. A review of global practices indicates that national government funding for satellite infrastructure is a common practice Footnote 77 and is necessary to protect critical satellite infrastructure.Footnote 78 In 2008, a United States (U.S.)-based company arranged to buy MacDonald Dettwiler and Associates (MDA).Footnote 79 At that time the federal government blocked the proposed sale under the Investment Canada Act, on the basis that it was not of “net benefit” to the country and cited RADARSAT-2’s importance to Canada’s security and sovereignty.Footnote 80

NRCan has longstanding expertise in remote sensing and geodesy making it adequately positioned to deliver the Essential Geographic Information Sub-program

Among most external stakeholders consulted, there is the expectation that NRCan should be the centre of expertise for geospatial information, remote sensing and geodesy given its broad mandate and long-standing experience and expertise. Some NRCan interviewees noted that the sub-program benefits from its placement because it provides good linkages to relevant science conducted at NRCan. Many NRCan and federal interviewees also noted that geospatial information continues to have important applications for natural resource exploration and use, and sustainable resource development.

However, some NRCan and federal representatives consulted viewed geodesy, geospatial information, remote sensing and earth observations to be misplaced at NRCan for two primary reasons: Geomatics has broad applications beyond natural resources; and it requires a stronger connection to innovation.

3.3 Alignment of sub-program with Federal and NRCan Priorities -Demonstrated

The sub-program is aligned with federal and NRCan priorities

Various NRCan Reports on Plans and PrioritiesFootnote 81 indicate alignment of the fundamental geodetic reference system, earth observation and mapping information to Strategic Outcome 3 – Canadians have information to manage their lands and natural resources. Fundamental geographic information helps to achieve this by providing support to the Canadian public and stakeholders to make informed decisions thereby facilitating the effective management of Canada’s natural resources and lands.Footnote 82

However, as many interviewees noted, remote sensing, geospatial information and geodetic services apply to a broad range of sectors in addition to natural resources. According to interviewees the sub-program has strong alignment with many national interests relating to the environment, innovation and public safety and security.

GeoBase programming is also aligned with Canada’s Action Plan on Open Government, a whole-of-Government initiative to ensure Canadians have easy access to the right information, in the right format, and in a timely manner, through reusable open data and applications.Footnote 83

Alignment of remote sensing science with NRCan priorities has been challenging due to their reliance on other federal funding. Interview and document evidence also indicated the need for better alignment with innovation, priority policy issues, and science-policy gaps.

4.0 Evaluation Findings: Effectiveness – Partially Demonstrated – Action Required

The evaluation focussed on access and use of information and services in its assessment of effectiveness. The use of geospatial and geodetic information and services in terms of the following:

- Enhanced access and use by target groups

- Benefits of use

- Improved decisions, policies, programs, research

- Increased operational efficiency, productivity

- Broader economic and environmental impacts

It should be noted that geospatial information can contribute both directly and indirectly to various outcomes. For example, in those cases where fundamental geospatial information is used to develop a value-added product or service, the impact of this information is less direct and more difficult to assess.

Summary:

Overall, evaluation evidence indicates that the sub-program is achieving its intended outcomes particularly with respect to improved government policies, programs and research in a variety of areas but most notably with respect to environmental monitoring and management, natural resource exploration and use. The evaluation evidence also suggests that geospatial information contributes to improved operational efficiencies and productivity benefits, but the magnitude of this impact is less clear.

However, full achievement of outcomes is limited by a number of factors both internal and external to NRCan including insufficient currency of GeoBase data, accessibility issues with respect to the GeoGratis website and the satellite imagery archiving catalogue; limited federal government receptor capacity for remote sensing applications; Inuvik satellite ground infrastructure uptake issues; inadequate FPT capacity to update GeoBase data; and insufficient CCRS technology transfer capacity.

4.1 Access and Use by Target Groups- Partially Demonstrated – Action Required

Overall the evaluation found, where adequate performance information was available, that geospatial information and products are being consistently accessed and used. This sub-section presents findings by key outputs given their distinct nature:

- GeoGratis data products and services;

- Remote sensing science;

- Satellite ground infrastructure; and

- Geodetic data and services.

Evidence suggests that GeoGratis data products and services have been consistently accessed by a broad range of stakeholders, but that inadequate GeoBase data quality and GeoGratis accessibility issues impeded full achievement of this outcome

GeoGratis data products (including GeoBase) are intended for a broad range of users including the general public, private sector, government and academia.Footnote 84 They are also intended for federal government decision-makers and policy advisors to facilitate better decisions and advice regarding horizontal priorities.Footnote 85 CCMEO sponsored user surveys and studiesFootnote 86 and the evaluation online surveyFootnote 87 suggest that a variety of stakeholder groups are accessing GeoGratis and GeoBase data products. According to survey evidence, GeoGratis data products are most commonly used for mapping, making decisions, supporting research and providing advice. Almost one-third of private sector respondents reported use of GeoGratis data products for infrastructure planning, engineering, and construction. Survey respondents indicated that GeoGratis data products are most frequently used for environmental monitoring and management, natural resources, water management and transportation. Federal interviewees ranked the Geographical Names Database as important to their work because it provides names to any authoritative map in Canada, such as fire maps produced by the Canadian Forestry Service.

The number of downloadsFootnote 88 of GeoBase data products has been fairly consistent from 2010-11 to 2015-16, averaging about 2.5 million downloads per year.Footnote 89 The most frequently downloaded products were Canadian Digital Elevation data, the National Hydro Network and Medium Resolution Satellite Imagery.

It is difficult to assess the extent to which GeoGratis products are being used given that the potential user population (i.e. size, profile) is unknown.Footnote 90 Interview and document evidence indicates that insufficient currency of GeoBase data significantly impedes its use for various applications such as emergency response. It was noted that some of the base data is decades out of date.

DocumentationFootnote 91 and the evaluation user survey (including professional user groups) indicate that there are significant access issues with the GeoGratis website. User suggestions for improvement most commonly focussed on improved usability and search function, and ease of accessing data. With respect to GeoGratis web servicesFootnote 92 interviewees suggests that the interface needs to be expanded to a larger portion of GeoBase data, to facilitate the efficient identification of data updates. It should be noted that many of the geospatial products have migrated to the Open Government Portal and the Federal Geospatial Platform. The FGP is intended to have efficient search capabilities (“search once and find everything”).Footnote 93

GeoGratis data products and services are being used to develop value-added products, applications or services

About one quarter of GeoGratis user respondents (n=177) reported that they developed value-added products, applications or services using GeoGratis data products.Footnote 94 With respect to GeoGratis web services, respondents (n=66) indicated that the services enabled development of a number of products such as customized maps (30%); interactive mapping applications (28%); or innovative services (16%).

An example of a value-added product that incorporates GeoBase data (and other federal and municipal data) is Esri’sFootnote 95 Community Map of Canada. Users can freely access the Map to develop geospatial information system software applications and can contribute their geographic information. Information from the Map is also incorporated into the World Topographic Map which has millions of page views per month.Footnote 96 Esri cites numerous benefits for participants of the Community Map such as reduction of costs associated with making data widely available.Footnote 97

Satellite imagery is being used by federal government stakeholders for decision-making, programs and research

Performance information was insufficient to determine the extent to which RADARSAT 2Footnote 98 data are accessed through the NEODF-Catalogue (archived data). Program documentation from 2010 estimated that approximately 30% of NEODF holdings had been re-used.Footnote 99 A case study examining Long-term Satellite Data Records (LTSDRs), a large component of the NEODF, indicated that various government departments, universities, private industry, as well as a number of international organizations use these records. The number of satellite frames processed by CCRS for Emergency Geomatics Services increases in line with flooding events.Footnote 100