Evaluation of the Forest Sector Innovation (FSI) Programs

Audit and Evaluation Branch

Natural Resources Canada

FINAL REPORT – December 30, 2019

Table of Contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Evaluation Objectives and Methods

- Evaluation Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

- Findings: Relevance

- Conclusions

- Appendix 1: Evaluation Team

List of Acronyms

- AEB

- Audit and Evaluation Branch

- CFS

- Canadian Forest Service

- CLT

- Cross-laminated Timber

- CWFC

- Canadian Wood Fibre Centre

- FRII

- Forest Research Institute Initiative

- FSI

- Forest Sector Innovation

- GHG

- Greenhouse Gas

- IFIT

- Investments in Forest Industry Transformation

- NBCC

- National Building Code of Canada

- NRCan

- Natural Resources Canada

- PCF

- Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change

- R&D

- Research and development

- SLAP

- Softwood Lumber Action Plan

- SME

- Small- and Medium-sized Enterprise

- TT

- Transformative Technologies

Executive Summary

About the Evaluation

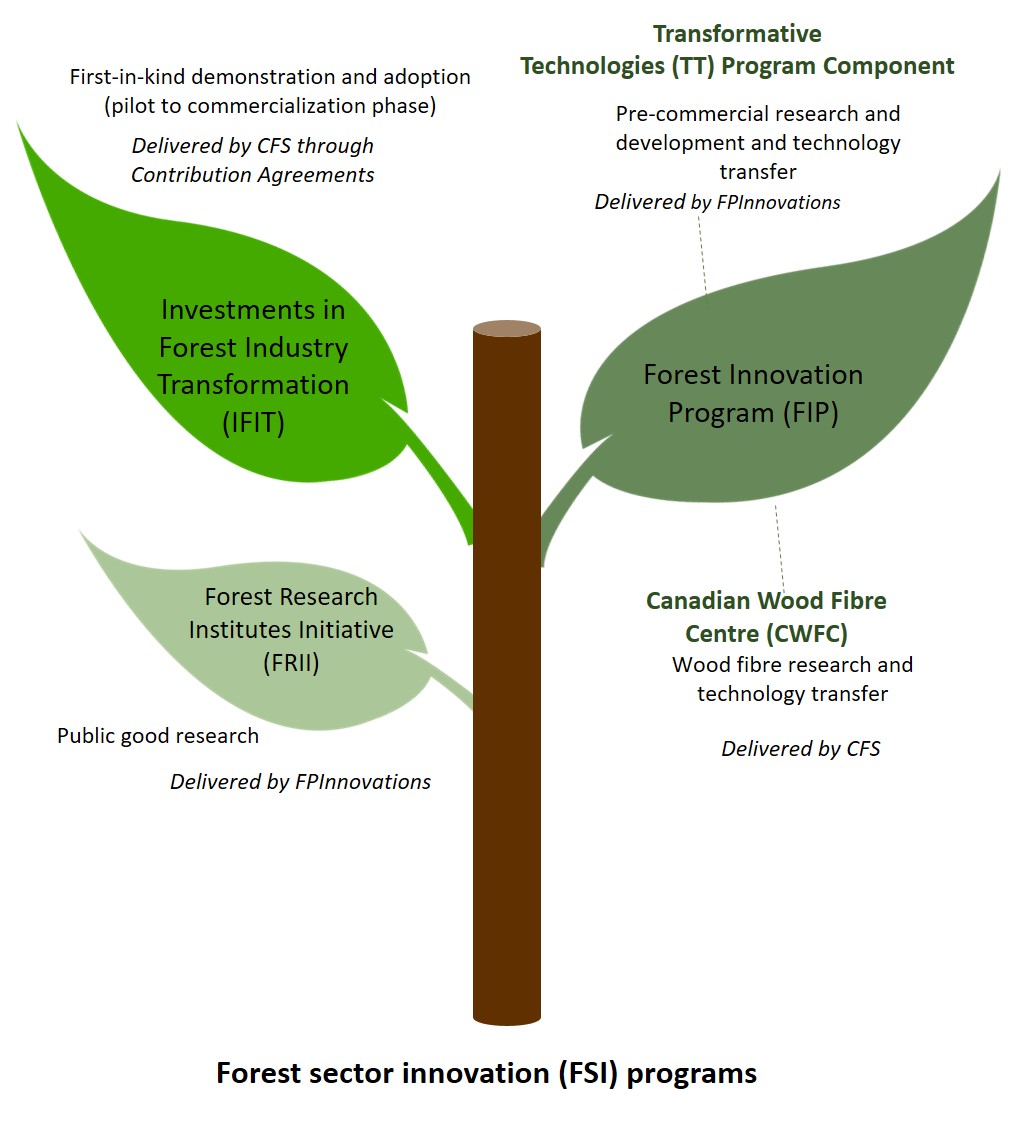

This report presents the findings, conclusions, and recommendations from the evaluation of the Canadian Forest Service’s suite of forest sector innovation programs (FSI) within the Forest Sector Competitiveness program. FSI encompasses the Investments in Forest Industry Transformation (IFIT) program; the Forest Research Institute Initiative (FRII); and the Forest Innovation Program (FIP). FIP is comprised of the Transformative Technologies (TT) program, which is its core component, and the Canadian Wood Fibre Centre (CWFC).

Collectively, the programs are designed to invest in innovative research, development and demonstration (RD&D), commercial pilots and knowledge transfer that will support the forest sector’s transformation to ensure its competitiveness. Two of these programs – the TT and the FRII programs are delivered by FPInnovations.

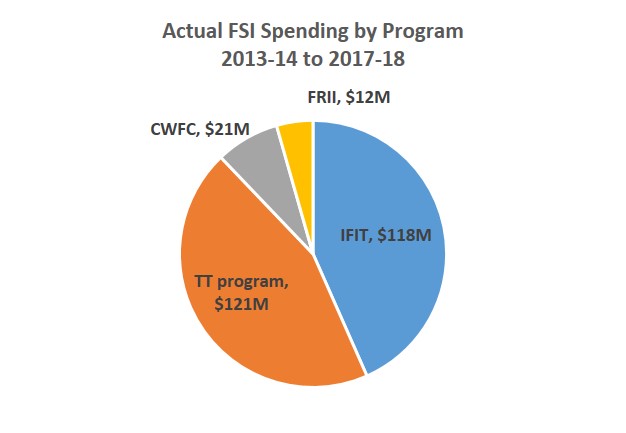

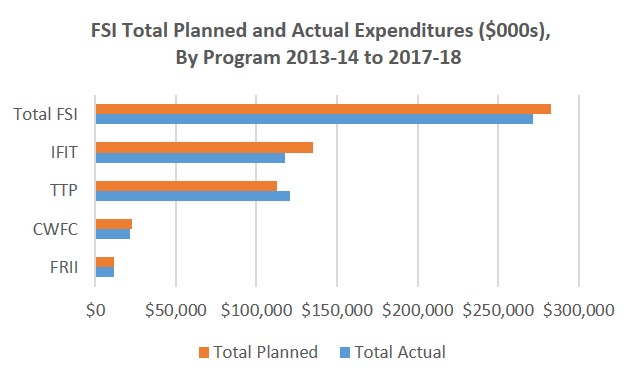

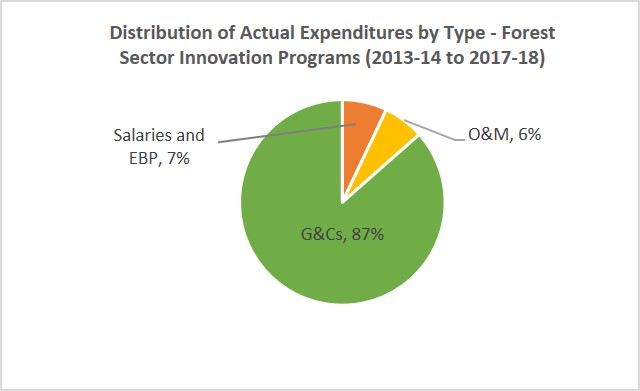

The evaluation covers the period from 2013-14 to January 2019. Actual expenditures for the programs (2013-14 to 2017-18) were approximately $271 million. IFIT and the TT program component account for most of these expenditures.

The objective of the evaluation was to assess the relevance, effectiveness and efficiency of the FSI program.

An evaluation of the Expanding Market Opportunities, covering a similar time period, is being conducted separately. This program, like the forest sector innovation programs, is part of the Forest Sector Competitiveness program.

What the Evaluation Found

Relevance

The evaluation found that the FSI programs continue to be relevant and aligned with federal government and NRCan roles and responsibilities, and priorities. These programs address a gap in funding support for high-risk innovation in the forest sector.

There is an ongoing need for the federal government to fund the FSI programs to address challenges to the sector’s competitiveness. There is also a growing recognition of the importance of FSI with respect to both climate change adaptation and mitigation solutions. The transition to the bioeconomy supports Canada’s environmental performance goals. The bioeconomy also has the potential to generate revenue streams from what may currently be considered forest waste products.

The forest sector’s significance to Canada’s economy supports the federal role in this area. Moreover, other national jurisdictions with significant forest sector economies, have comparable innovation programs to increase competitiveness and to advance the bioeconomy.

The location of the programs at the federal level helps to even the playing field in cases where there is variation in provinces’ capacities to support forest sector innovation, and provides a “big picture” understanding of threats and opportunities affecting the national forest sector. Utilizing a collaborative model, CFS is well-positioned to deliver research programs that are aligned with industry needs.

With respect to the TT program component, which is delivered by FPInnovations, our evaluation found that the CFS role with respect to the TT planning process, needs to be strengthened to ensure an appropriate balance between transformative and incremental activities. Stakeholders generally noted that while a mix of incremental and transformative activities is appropriate, they perceived that the TT program component requires more emphasis on transformative innovation.

Effectiveness

Evaluation evidence suggests that FSI has made progress towards its intended outcomes with respect to developing and advancing innovations, and providing evidence for codes, standards, policy-development, and decision-making pertaining to forest management and sustainable development.

Specific areas of progress include:

- Advanced building systems: The TT and IFIT programs have contributed to the adoption of advanced building systems such as mid-rise building wood-construction by informing the development of supporting codes; improving technologies and higher-value products (eg., cross-laminated timber); piloting technologies and automated production systems; and by producing technical guidance products for industry.

- Bioproducts: The TT program has resulted in significant advancement of novel bioproducts (i.e., cellulose nanocrystals, cellulose filaments, and lignin). Progress has been made in developing various product applications for these materials. These bioproducts have the potential to be used as a raw material for different products and to replace petroleum-based raw materials that are in a wide range of products (e.g., plastics).

- Enhanced Forest Inventory: CWFC has made substantial contributions to provincial and industry uptake of enhanced forest inventory tools and practices. Enhanced Forest Industry technologies provide better information for the assessment of wood and fibre attributes to inform forest planning and management decisions.

While CFS has made inroads into strengthening its engagement, transitioning to a bioeconomy will require efforts to further broaden linkages with a range of stakeholders, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), other sectors, and academia.

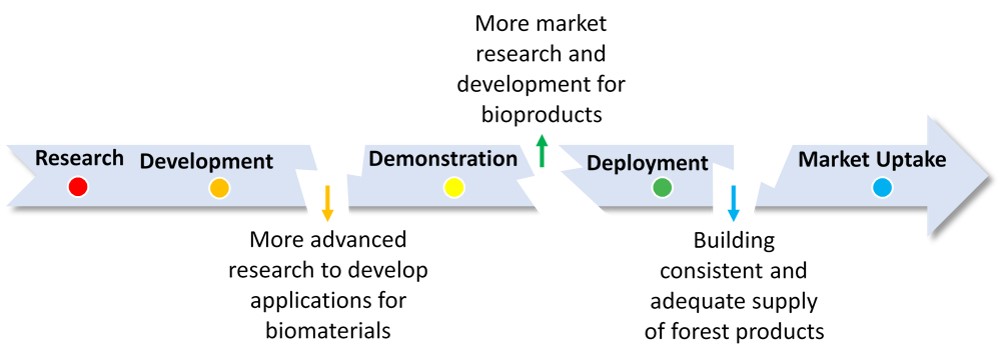

Program effectiveness is also affected by the insufficient capacity of the forest sector to use research to innovate. Our evaluation found that there were innovation gaps impeding outcome achievement. These include the need for more advanced bioproduct applications research, market research and support for novel products; and the need for a more secure supply of bioproducts.

Some early economic benefits have been observed at the firm level, therefore suggesting that the programs are paving the way for long-term improved forest sector competitiveness. IFIT, a program that targets the later stages of the innovation continuum is making good progress. Completed IFIT projects are reporting positive economic benefits such as increased return on investment and revenues.

While the forest sector continues to rely heavily on commodity products, there has been some progress with respect to the development and production of higher value wood products.

Efficiency

Evaluation evidence suggests that several aspects of the program design and delivery contribute to the efficient production of deliverables and results. The collaborative model and its broad-spectrum approach were frequently cited as key strengths of the FSI programs. In addition, CFS undertakes periodic assessments of its research directions, workplans, and progress.

FPInnovations, a central hub for research, was cited by external stakeholders as an effective model for collaborative and non-proprietary research and development. However, they viewed its membership structures, which was being modified at the time of this evaluation, as constraining the Transformative Technologies program and increasing the risk that the program is not optimally reaching its target groups.

IFIT delivers large, complex projects and has experienced challenges relating to the periodic call for proposals process which was reported to constrain selection of projects to those that had a higher level of preparedness at the time of the calls. In addition, stakeholders suggested that funding rules restricting the carry over of funds from one fiscal year to another should be made more flexible in light of the realities of large-scale innovation projects, which depend on many external, sometimes unpredictable, factors. Finally, our evaluation found that there is a need to identify and implement novel approaches to encourage more high risk projects.

A review of performance information identified several performance measurement issues. Our evaluation team found that FIP (TT program and CWFC) and FRII reports lacked overall aggregate reporting on program status and outcomes, making it challenging to assess the extent of outcome achievement of FIP. Better metrics and methods are needed to measure outcomes such as technology advancement. In addition, the use and uptake of knowledge products and decision-making tools is not typically reported. IFIT does a reasonably good job of monitoring its key outputs and outcomes, but its program reports lack clarity.

Recommendations

| Recommendation | Management Response |

|---|---|

| 1. The Canadian Forest Service should play a stronger role to ensure that the Transformative Technologies program has an optimal balance of transformative and incremental innovation activities to support the transition to the bioeconomy. | Management agrees with this recommendation As part of FPInnovations redesign of their research strategy, the Canadian Forest Service (CFS) will actively participate and influence the planning process of their work plan to ensure there is emphasis on transformative innovation activities in support of the CCFM Forest Bioeconomy Framework. The evolution of the new TT program will target both transformative and incremental innovation activities.(more details provided in Recommendation #2). (ADM, CFS responsibility) Target Date: March, 2020 |

| 2. The Canadian Forest Service should work with its partners to further broaden the programs’ reach and increase collaboration with SMEs, academia, and other sectors. The Canadian Forest Service should consider and implement novel approaches for pilot projects to increase collaboration and knowledge transfer between industry, FPInnovations, and academia. | Management agrees with this recommendation The CFS will work with partners to increase its collaboration with SMEs, academia and other sectors. The IFIT program will use the small enterprises stream to target SMEs through more aggressive outreach activities for upcoming calls for proposals. Small enterprises follow a streamlined application and due diligence process as outlined in the IFIT guidance document on how to submit a proposal. The CFS will also work to improve direct funding opportunities, collaboration and knowledge transfer with academia, national organizations, SME’s and other industrial sectors through the launch of competitive pilot project platform collaborations with FPInnovations, industry and academia. In particular, CWFC will widen its reach, by working more closely with FPInnovations on national collaborative projects to increase the development and deployment of scientific tools and products to the forest industry and provinces. (ADM, CFS) Target Date: March, 2020 |

| 3. The Canadian Forest Service should work with partners to advance projects that will address pre-commercialization innovation gaps. | Management agrees with this recommendation The CFS will work with partners to address pre-commercialization innovation gaps where no current funding is available. This will be accomplished through market research studies for novel products and bioproduct applications R&D needed to bring biomaterials to market. The IFIT program’s Feasibility Studies project category will be expanded to include different types of assessments needed to bridge gaps in the innovation spectrum. This component will now be called Complementary Studies. Examples of eligible projects include feasibility studies for innovation technologies or trials for market acceptance of new bioproducts. (ADM, CFS) Target Date: March, 2020 |

4. The Canadian Forest Service should improve its performance measurement and reporting of its programs and projects:

|

Management agrees with this recommendation CFS has developed a solid approach by following a methodology for effective performance reporting according to the Performance Information Profile (PIP) for the Fibre Solutions and the Forest Sector Competitiveness programs. In addition, work is underway to strengthen and streamline the performance measurement system and performance metrics, including GBA+ considerations, as part of the renewal efforts of Budget 2019. CFS will assess the feasibility of using a CRM tool which would be planned to be available by summer 2020. (ADM, CFS) Target Date: March, 2020 for new methodology, ongoing for implementation through to March 2023 |

5. The Canadian Forest Service should work with Treasury Board Secretariat to enhance elements of IFIT’s design and delivery. These changes would facilitate optimal project selection, encourage high risks projects, and improve the management of complex, innovation projects:

|

Management agrees with this recommendation As part of the Budget 2019 program renewal, IFIT will be exploring ways to increase flexibility for its applicants and recipients:

|

Introduction

This report presents the findings, conclusions, and recommendations from the evaluation of the Canadian Forest Service’s (CFS) suite of forest sector innovations programs (FSI), covering the period from 2013-14 to January 2019. The FSI programs encompass the Investments in Forest Industry Transformation (IFIT) program; the Forest Research Institute Initiative (FRII) and the Forest Innovation Program (FIP). FIP is comprised of the Transformative Technologies (TT) program, the key component, and the Canadian Wood Fibre Centre (CWFC).

Budget 2019 proposes an investment of up to $174.7 million over three years for the continued delivery of IFIT, and FIP. Results of the evaluation will help inform requests for program renewal.

These programs each target a different section of the innovation continuum, including fundamental research, development, demonstration, and early deployment. The FSI programs are part of the Departmental Results Framework’s Forest Sector Competitiveness Program.

Natural Resources Canada’s (NRCan) Audit and Evaluation Branch (AEB) undertook the evaluation between May 2018 and June 2019. It was conducted in accordance with the 2016 Treasury Board Policy on Results, and responds to requirements under section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act as well as a Treasury Board commitment to evaluate the programs by March 2019.

Program Information

Since the inception of FIP and FRII in 2007 and IFIT in 2010, these programs have been intended to increase the sector’s competitiveness through innovation for sector transformation. This has been particularly important during challenging economic times for the sector, such as the 2008 recession and during the ongoing Canada-U.S. softwood lumber dispute. In fact, the programs are continuing under the federal Softwood Lumber Action Plan. Collectively, the programs are designed to invest in innovative research, development and demonstration (RD&D), commercial pilots and knowledge transfer that will support the forest sector’s transformation to producing higher-value forest products. Whereas the CWFC and IFIT aspects are delivered by NRCan CFS staff, the TT program component and FRII are delivered by FPInnovations, a not-for-profit research institute that receives funding from federal, provincial and industry stakeholders to undertake collaborative pre-commercial research and development for the forest sector, as well as undertake technology transfer activities.

Text version

Description: Forest sector innovation (FSI) programs. An infographic describing the Forest Sector Innovation (FSI) Programs. The first program is the Forest Research Institutes Initiative (FRII), which undertakes public good research and is delivered by FPInnovations. The second program is the Investments in Forest Industry Transformation (IFIT) program, which supports first-in-kind demonstration and adoption (pilot to commercialization phase) and is delivered by CFS through Contribution Agreements. The third program is the Forest Innovation Program (FIP), which is composed of two components: the Transformative Technologies (TT) Program, and the Canadian Wood Fibre Centre (CWFC). The TT Program supports pre-commercial research and development and technology transfer, and is delivered by FPInnovations. CWFC supports wood fibre research and technology transfer, and is delivered by CFS.

FPInnovations’ research plan is developed with guidance from the organization’s Board of Directors— of which the Assistant Deputy Minister of the CFS is an observer— as well as in consultation with the organization’s members and six program advisory committees, which were being modified at the time of this evaluation. CFS performs oversight of the activities of FPInnovations’ and its partners under Contribution Agreements for the TT program and FRII.

As part of FIP, the TT program supports FPInnovations to deliver collaborative, pre-commercial, non-proprietary research, development and demonstration (RD&D), commercial pilots and technology transfer for innovative technologies and processes in the forest sector. These investments are intended to lead to a more value-chain approach to Canadian forest products.

With employees located across the country, CWFC works closely with FPInnovations and other stakeholders to undertake wood fibre research and facilitate end-user uptake. CWFC aims to develop targeted and environmentally responsible solutions to challenges faced by Canada’s forest industries.

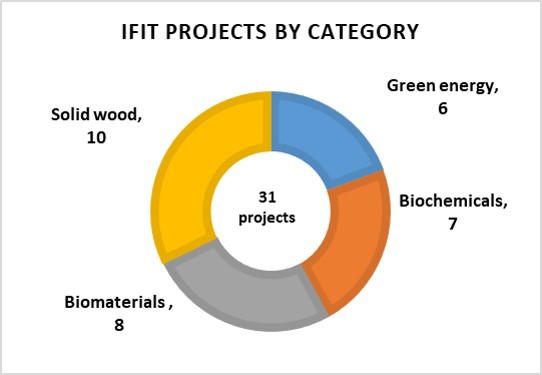

The IFIT program offers non-repayable contributions to successful applicants to implement innovative, first-in-kind technologies in their facilities. The program provides funding for large-scale demonstration projects, as well as commercial pilots, with a view to helping these technologies get to market. From its inception to 2018-19, IFIT has funded 31 projects. These projects fall into the following categories: Green Energy (6), Biomaterials (8), Solid Wood (10), and Biochemicals (7).

Text version

Description: IFIT Projects by Category. A pie chart showing the distribution of the 31 IFIT-supported projects by category. Of the 31 IFIT-supported projects, 10 are in the solid wood category, 8 in biomaterials, 7 in biochemicals, and 6 in green energy.

Text version

Description: Actual FSI Spending by Program 2013-14 to 2017-18. A pie chart showing the distribution of actual total FSI spending by program from 2013-14 to 2017-18. During this time, IFIT accounted for $118 million in expenditures, followed by the TT Program for $121 million, CWFC for $21 million, and FRII for $12 million.

Actual Expenditures by Program

The FSI programs represent approximately $271 million (M) in NRCan expenditures from 2013-14 to 2017-18. IFIT and the TT program have the highest expenditures with $118M and $121M respectively. During this time, IFIT funded 20 projects, and the TT program, CWFC, and FRII funded an average of 95 projects per year. With the exception of FRII, which receives A-base funding, the FSI programs primarily receive C-base funding.

Evaluation Objectives and Methods

The objective of this evaluation is to assess the relevance (i.e., continued need and alignment with federal and NRCan priorities and roles/responsibilities) and performance (i.e., effectiveness and efficiency) of the CFS Forest Sector Innovation programming (FSI) and to consider how the program’s design influences effectiveness.

The evaluation used six key lines of evidence, consisting of qualitative and quantitative data:

| Document Review | Literature Review | Database and File Review | Key Informant Interviews | Industry online survey | Case Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A review of program documents, as well as strategic and corporate documents for NRCan, the federal government and FPInnovations. This line of evidence informed findings across all evaluation questions. | A review of published literature, with a focus on best practices in forest sector innovation and innovation systems in Nordic countries. | A review of project-specific financial and results data from IFIT’s database. To minimize selection bias, projects (2017-2018 and 2018-2019) were randomly selected, including 30 from the TT program, 11 from FRII, and 9 from CWFC. |

Ninety (90) interviews were conducted (11 of which were NRCan representatives and 79 were with external stakeholders -industry, provinces/ territories, and academia). | An online survey of industry stakeholders was conducted to solicit views on the programs’ relevance and performance, facilitating factors and barriers to innovation. The survey had a 25% response rate (n=58); the majority of respondents were from small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and organizations that did not receive funding from the FSI programs. | The evaluation completed six case studies to understand the impacts and influencing factors related to the following themes/ projects: TMP-Bio project; advanced building systems; cellulose nanocrystals; AE Côte-Nord Bioenergy project; extracting lignin for new forest products; and enhanced forest inventory. |

Evaluation Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

The evaluation used multiple lines of evidence in order to mitigate any limitations associated with individual methods. These enabled the triangulation of evidence across sources of information to identify valid findings and conclusions relative to the evaluation questions. Nevertheless, the following limitations and mitigation strategies should be considered when reviewing the findings from this evaluation:

- Numerous studies and analyses of the broader impacts of R&D note that there exists a long lag time between investment in research and realization of tangible productivity gains. To mitigate for this challenge the case studies and document review included a longitudinal view of the FSI programs’ contributions, sometimes going back years before this evaluation period. This longitudinal view illustrates the timelines for achievement, as well as the various factors that influence effectiveness.

- The evaluation included a survey of industry stakeholders. These stakeholders were drawn primarily from a CFS mailing list and also from other relevant industry lists from various sub-sectors (located on the Internet). The response rate of 25% was within acceptable survey standards, but the sample size was small (n=58), making credible comparisons among survey sub-groups (e.g. smaller and larger firms, different sub-sectors) impossible.

The sample was primarily made up of small organizations (less than 100 employees), who produced a variety of forest products. However, because the sample is not representative of the forest industry and its various sub-sectors, the evaluation utilizes the survey results with caution and cites the results when corroborated by other lines of evidence.

Most of the survey respondents were neither members of industry associations or FPInnovations nor participants in CFS forest sector programs. This did help to achieve the evaluation’s intention to reach beyond recipients of program contributions and better assess the relevance of the program and the barriers and opportunities for innovation.

What We Found

Relevance

To what extent is there a continued need for the program?

To what extent is the program aligned with federal government and NRCan priorities, roles and responsibilities?

Findings: Relevance

Summary:

There is an ongoing need for the FSI programs to address challenges to the sector’s competitiveness and to contribute to sustainable development goals and climate change adaptation and mitigation efforts. These programs address a gap in funding support for high-risk innovation in the forest sector.

The CFS leadership role in facilitating the sector’s transformation is appropriate, particularly in the context of the collaborative approach utilized by CFS. CFS is positioned to deliver research programs aligned with industry needs, given its mandate, longstanding experience, and expertise. NRCan has a legislated role to conduct research with the Forestry Act, stating that the Minister “shall provide for the conduct of research relating to the protection, management and utilization of the forest resources of Canada.” Interviewees also noted that the location of the programs at the federal level helps to even the playing field in cases where there is variation in provinces’ capacities to support forest sector innovation, and provides a “big picture” understanding of threats and opportunities affecting the national forest sector.

Evidence suggests, that CFS play a more influential role in the TT planning process to ensure that there is sufficient emphasis on transformative activities and that there is an optimal balance of transformative and incremental activities.

Recommendations 1

The Canadian Forest Service should play a stronger role to ensure that the Transformative Technologies program component has an optimal balance of transformative and incremental innovation activities to support the transition to the bioeconomy.

Management Response

Agreed. As part of FPInnovations redesign of their research strategy, the Canadian Forest Service (CFS) will actively participate and influence the planning process of their work plan to ensure there is emphasis on transformative innovation activities in support of the CCFM Forest Bioeconomy Framework. The evolution of the new TT program will target both transformative and incremental innovation activities. (More details provided in Recommendation #2).

Target Date: March, 2020

There is a continued need for the forest sector innovation programs

All relevant lines of evidence confirm that there is an ongoing need for the Investments in Forest Industry Transformation program, the Forest Innovation Program (Transformative Technologies program component and the Canada Wood Fibre Centre), and the Forest Research Institute Initiative (FRII). Collectively these programs aim to increase the forest sector’s competitiveness while supporting the transition to the bioeconomy and a low-carbon economy future.

The Forest Bioeconomy is…

“… Economic activity generated by converting sustainably managed renewable forest-based resources, primarily woody biomass and non-timber forest products, into value-added products and services using novel and repurposed processes.”

(Source: A Forest Bioeconomy Framework For Canada. 2017)

Towards a low-carbon future

In addition to CFS support of the transformation of the forest sector in order to align with long-term needs and increased competitiveness, there is now an additional emphasis on the forest sector’s role to support the transition to the bioeconomy.

Whereas previously the term “transformation” of the sector described the diversification of forest sector products and markets beyond the traditional commodity base to encompass higher-value forest fibre products, the transition to the bioeconomy involves the creation of novel and sustainable advanced bioproducts (e.g., cellulose filaments) that facilitate the transition to a low-carbon economy future.

Bioproduct sectors around the world are forecasted to expand over the next few years. Forests are recognised as a significant contributor to any development of a bioeconomy as a source of renewable biomass. Globally the key drivers are climate change, sustainable development and economic development.

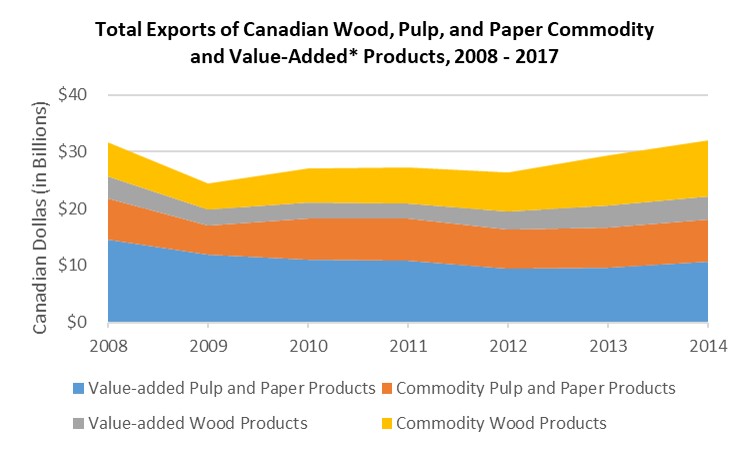

The sector’s reliance on its commodity base has left it vulnerable to changes in market conditions, as evidenced during the 2008 recession and the ongoing Canada – U.S. softwood lumber dispute. In addition, the market for newsprint and printing paper continues to decline. The development of new products and new applications for existing forest products is expected to help the forest sector adjust to changes in market demands. Stakeholders indicate that both the TT program and IFIT play a valuable role in de-risking innovation and in developing higher-value fibre products.

Documents indicate that fibre feedstock is the single largest cost for the forest industry and that the fibre supply is declining (primarily attributed to climate change impacts). The TT program’s work related to maximizing the value of fibre and more efficient harvesting and use of forest materials is particularly relevant to this context. In addition, CWFC’s silviculture work designed to improve growing rates and fibre quality is aligned with the need to optimize the value of wood fibre.

The Forest Sector Innovation programs can play a role in addressing climate change adaptation and mitigation needs

There is a growing recognition, as indicated by peer-reviewed articles and interviews with experts, of the potentially important role of the programs with respect to both climate change adaptation and mitigation. According to our literature review, optimal environmental benefits are most likely to be realized when combined with several strategies such as sustainable forest management practices, efficient forest product utilization, high residue recovery rates, including residue from wood waste and high efficiency utilization of harvested biomass. Moreover, stakeholder feedback also confirms that the bioeconomy is perceived as very important, with the potential to generate revenue streams from what may currently be considered waste products.

There is a strong correlation between innovation and competitiveness

The evaluation team’s review of academic literature concluded that innovation development and adoption is an important part of facilitating the long-term competitiveness of the forest sector. In addition to supporting forest sector transformation, innovation allows the sector to expand into non-traditional markets, increase sector productivity, and compete globally by targeting markets for niche products. Interviewees also highlighted the critical role of the TT program component and FRII’s research on codes and standards in increasing market access and facilitating the commercialization and adoption of technologies.

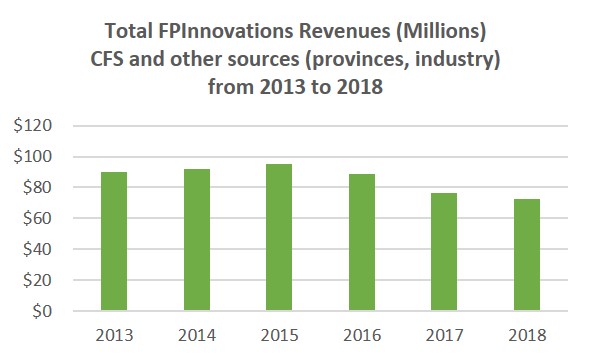

Continuing federal funding for the TT program and FRII allows FPInnovations to maintain a consistent research budget directed towards collaborative, non-proprietary research

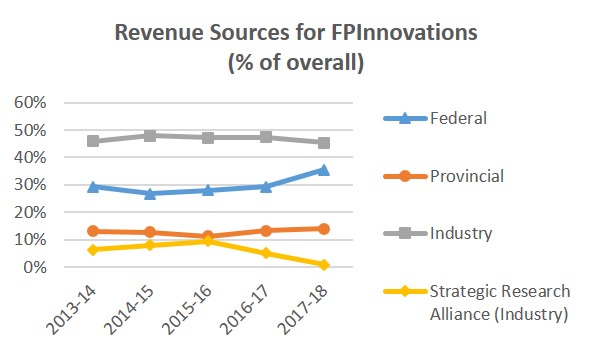

Findings from stakeholder interviews and program documents indicate that the TT program and FRII funding allows FPInnovations to maintain a consistent collaborative research budget, therefore supporting continued innovation activities despite changes in market conditions and industry support. There was a decline in FPInnovations’ revenue from 2015 to 2018. This decline is partially attributed to the drop in funding from FPInnovations’ Strategic Research Alliances, which are funded by industry. These alliances are partnerships between FPInnovations industry members and other stakeholders to undertake more advanced research. Federal funding represents an increasing proportion of FPInnovations’ revenue during this time.

Text version

Description: Total FPInnovations Revenues (Millions) from CFS and Other Sources (Provinces, Industry) from 2013 to 2018. Bar graph depicting total FPInnovations revenues (in millions) from CFS and Other Sources (provinces, industry) by year from 2013 to 2018.

| Total FPInnovations Revenues (Millions) from CFS and Other Sources (Provinces, Industry) from 2013 to 2018 | |

|---|---|

| 2013 | $89.7 |

| 2014 | $91.8 |

| 2015 | $95.4 |

| 2016 | $88.6 |

| 2017 | $76.1 |

| 2018 | $72.5 |

Text version

Description: Revenue Sources for FPInnovations (% of Overall). Line graph depicting the relative revenue for FPInnovations by year from federal, provincial, industry, and its strategic research alliance partnerships from 2013-14 to 2017-18.

| Source | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federal | 29% | 27% | 28% | 29% | 36% |

| Provincial | 13% | 13% | 11% | 13% | 14% |

| Industry | 46% | 48% | 47% | 47% | 45% |

| Strategic Research Alliance (Industry) | 6% | 8% | 9% | 5% | 1% |

The Forest Sector Innovation Programs are aligned with federal government and NRCan priorities and responsibilities

The FSI programs are aligned with the Government of Canada’s priorities to enhance the competitiveness of the natural resources sectors and environmental performance. The programs demonstrate alignment to Government commitments under the 2016 Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change (PCF). A review of program documents found that the programs align with the transition to a low-carbon economy by identifying opportunities to produce bioproducts and bioenergy, supporting innovation for sustainable forest operations and high-value fibre products, and facilitating the market adoption of environmentally-friendly wood construction and bioproducts.

Through these actions, the programs are also consistent with the pillars of the 2017 Canadian Council of Forest Ministers’ Forest Bioeconomy Framework. The programs also reflects several objectives of the 2016 to 2019 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy: effective action on climate change; modern and resilient infrastructure; greening the environment; clean energy; clean growth; and sustainably managed lands and forests.

The federal government’s role is consistent with forest sector innovation. The Natural Resources Act, which states that the Minister of Natural Resources shall “seek to enhance the responsible development and use of Canada’s natural resources and the competitiveness of Canada's natural resource products”. It is also consistent with the Forestry Act, which states that the Minister “shall provide for the conduct of research relating to the protection, management and utilization of the forest resources of Canada.”

FSI programs are aligned with Government of Canada priorities related to transitioning to a low carbon economy; enhancing forest sector competitiveness; and environmental performance of the forest sector as identified in the following federal initiatives:

- Pan American Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change – e.g., transition to a low carbon economy

- Canadian Council of Forest Ministers Forest (CCFM) Bioeconomy Framework for Canada

- Federal Sustainable Development Strategy

While other federal government departments also support innovation programs, external stakeholders interviewed believe that NRCan has the appropriate expertise and experience to support FSI programming. In addition to its expertise on all parts of the fibre value chain, interviewees noted that CFS’s strong connections with industry stakeholders position it well to deliver research programs aligned with industry needs. However, stakeholders also noted that the transition to the bioeconomy will require more integration and coordination with other sectors. CFS has taken steps to achieve this through their support of CCFM’s Bioeconomy Framework and the development of a federal bioeconomy strategy (in progress during the time of the evaluation) in coordination with other federal partners.

In addition, the location of innovation funding supports at the federal level also helps to level the playing field in cases where there is variation in provinces’ capacities to support forest sector innovation, and provides a “big picture” understanding of threats and opportunities affecting the national forest sector.

The forest sector is a significant contributor to Canada’s economy

The federal role is appropriate because the forest sector is a significant contributor to Canada’s economy.

The forest sector represents about 1.6% of Canada’s GDP ($24.6 billion)

Directly employs close to 210,000 people, primarily in rural areas

(Source: The State of Canada's Forests Report. 2018)

Other national jurisdictions with sizeable forest sector economies have comparable innovation programs to increase competitiveness and to advance the bioeconomy

Investing in innovation to combat challenges to the forest sector’s competitiveness is not unique to Canada. Other governments with significant forest sector economies, such as Finland, Sweden, and Australia, have created programs to support innovation in the forest sector, increase its competitiveness and advance the bioeconomy.

Stakeholders consider long-term, high-risk research to be an appropriate area for federal government involvement

The FSI programs typically target long-term, high-risk innovation that would not likely be undertaken by other stakeholders. The TT program and CWFC support pre-competitive research, an area, according to stakeholders, where industry is less likely to be involved. IFIT funds first-in-kind commercial scale technologies in the forest sector due to their high-risk; this allows the program to de-risk innovation at this stage. This is considered an appropriate role for government because the first in industry to pilot an innovation is usually unable to capitalize on their advantage, or access funding from investors.

The FSI programs address the lack of funding options available for high-risk innovation in the forest sector. Interview, survey and document evidence indicated that this is a significant barrier to innovation in the sector, and that the private sector is less likely to invest in high-risk innovation. Evidence from our survey, interviews and the literature review indicates that insufficient capital and difficulties in accessing external financing are among the most significant challenges for industry in developing innovations.

CFS leadership is required to ensure an appropriate balance between incremental and transformative research

Incremental versus Transformative

Incremental innovation involves a series of small changes to an existing product or practice. It typically involves refining existing procedures with a view to reducing costs.

Transformative innovation generally involves the replacement of an existing product with a new one. The new product is usually in competition with the existing one.

Stakeholders generally noted that while a mix of incremental and transformational activities is appropriate, they perceived that more emphasis on transformative innovation is needed to support the transition to the bioeconomy. Evaluation evidence indicates that FPInnovations’ design limited CFS’s influence on the TT program component’s research directions. Stakeholders suggested that CFS develop clearer guidance as to what activities are transformative in light of its priority to transition to the bioeconomy.

In our review of a random sample of TT project files (2017-2018), about half of the projects supported incremental innovation. However, of the total budget for the sampled projects, about one third of the budget was allocated to incremental research versus two thirds of the budget to transformative research. While it is not known if this budget allocation is representative of the past five years, it does suggest that a considerable portion of the TT program’s activities is being directed towards incremental innovation.

What We Found

Effectiveness

To what extent do FSI program activities result in expected outcomes?

What factors are influencing effectiveness?

Performance - Effectiveness

Summary:

Evaluation evidence indicates that the forest sector innovation programs have made good progress towards the achievement of their intended immediate and intermediate results: developing and advancing technologies and knowledge; and providing evidence for codes, standards, policy-development, and decision-making related to forest management and sustainable development. CFS has made inroads into broadening its engagement, but transitioning to a bioeconomy will require efforts to further expand collaborations with SMEs, academia and non-traditional stakeholders from other sectors.

While the programs contributed significantly to the adoption of advanced building systems (e.g. mid-rise wood-frame construction), high-value wood products (e.g., cross-laminated timber), and enhanced forest inventory practices, this adoption is not yet widespread. Evaluation evidence also suggests that FSI has also contributed to the adoption by industry of harvesting, operational, transportation and manufacturing efficiencies, but the extent of this adoption is unknown.

Evaluation evidence suggests that the programs have positively influenced adoption outcomes not only through funding for technology advancement, but also through the programs’ enabling role, for example, support for codes and standards development, and through CFS brokering and networking activities.

Program effectiveness is affected by insufficient capacity of the forest industry to use research to innovate (i.e., low industry receptor capacity); and innovation gaps such as advanced product applications research, market research for novel products, and the need for a more secure supply of bioproducts to improve market uptake.

Inadequate performance information with respect to the FIP (TT and CWFC) and unclear program targets made it challenging to assess the extent of outcome achievement

Recommendation 2:

The Canadian Forest Service should work with its partners to further broaden the programs’ reach and increase collaboration with SMEs, academia, and other sectors. The Canadian Forest Service should consider and implement novel approaches for pilot projects to increase collaboration and knowledge transfer between industry, FPInnovations, and academia.

Management Response

Agreed. The CFS will work with partners to increase its collaboration with SMEs, academia and other sectors. The IFIT program will use the small enterprises stream to target SMEs through more aggressive outreach activities for upcoming calls for proposals. Small enterprises follow a streamlined application and due diligence process as outlined in the IFIT guidance document on how to submit a proposal.

The CFS will also work to improve direct funding opportunities, collaboration and knowledge transfer with academia, national organizations, SME’s and other industrial sectors through the launch of competitive pilot project platform collaborations with FPInnovations, industry and academia. In particular, CWFC will widen its reach, by working more closely with FPInnovations on national collaborative projects to increase the development and deployment of scientific tools and products to the forest industry and provinces. Target Date: March, 2020

Recommendation 3:

The Canadian Forest Service should work with partners to advance projects that will address pre-commercialization innovation gaps.

Management Response

Agreed. The CFS will work with partners to address pre-commercialization innovation gaps where no current funding is available. This will be accomplished through market research studies for novel products and bioproduct applications R&D needed to bring biomaterials to market.

The IFIT program’s Feasibility Studies project category will be expanded to include different types of assessments needed to bridge gaps in the innovation spectrum. This component will now be called Complementary Studies. Examples of eligible projects include feasibility studies for innovation technologies or trials for market acceptance of new bioproducts. Target Date: March, 2020

FSI programs are progressing towards their intended immediate and intermediate results

Expected Results

Immediate Outcomes

- Broad engagement and enhanced collaboration of key stakeholders

- New and enhanced knowledge, products, processes, tools, technologies, scale-up of advanced technologies

Intermediate Outcomes

- Codes, standards and forestry management and policy decisions are informed by science

- Technologies, processes, sustainable forestry management practices are implemented and adopted

Ultimate Outcomes

- Improved competitiveness (more diversified, higher value product mix)

- Improved environmental sustainability of Canadian forest industry

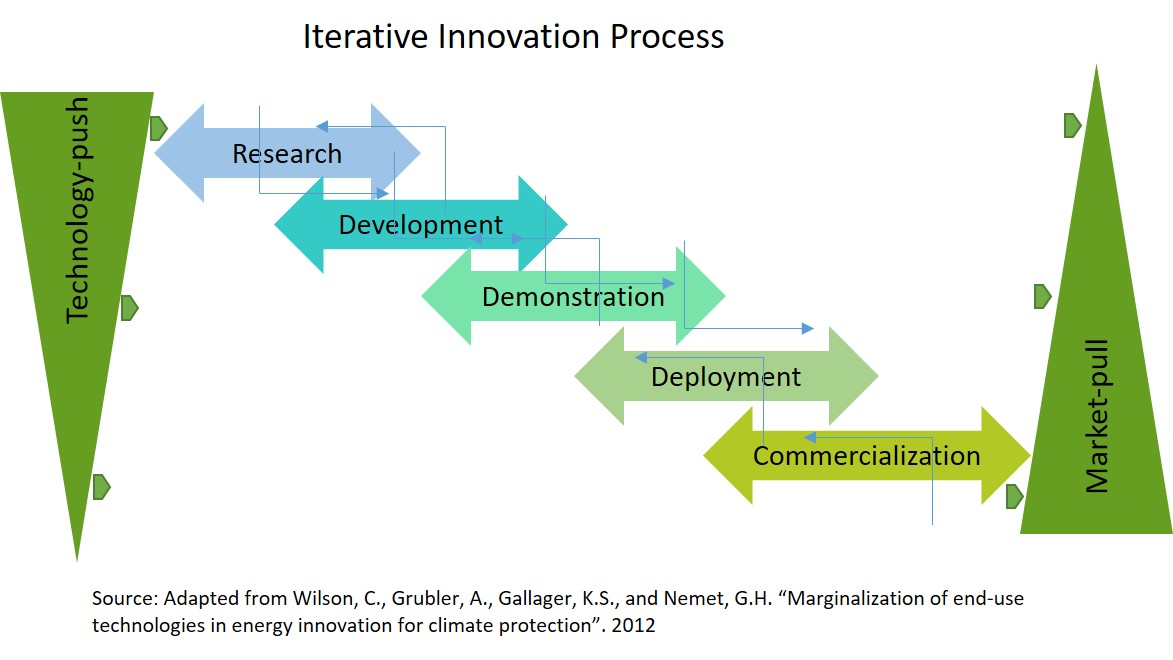

Innovation takes time and does not progress along a linear path

Prior to presenting the findings on outcomes, it is useful to understand how innovations typically progress. A literature review on innovation indicates that there is typically a significant time lag from early stage research to commercialization. Moreover, the innovation process is unpredictable. Knowledge created during the various stages of innovation can inform further research at an earlier stage on the continuum.

Innovation is also cumulative - the more the knowledge base grows, the better the capacity develops to address barriers to technology adoption, such as the initial high costs of technologies. Therefore, measures of success for an innovation program have to consider not only how technologies advance, but also how the knowledge generated throughout the innovation process is shared and used.

The stages of the innovation continuum

Text version

Description: Iterative Innovation Process. Infographic demonstrating the non-linearity of the iterative innovation process. At every stage of the innovation continuum, the process is influenced by technology push and market pull factors, which can lead to continuous progress along the continuum, or a need to return to an earlier portion of the continuum. Even following the commercialization of a technology, it may be necessary to return to resume research and development to enhance the product or to better reflect market needs. Source: Adapted from Wilson, C., Grubler, A., Gallager, K.S., and Nemet, G.H. “Marginalization of end-use technologies in energy innovation for climate protection”. 2012.

Research – Early research and proof of concept.

Development – Method testing and development, as well as developing prototypes.

Demonstration – Demonstration of prototypes and identifying areas for improvement.

Deployment – Large-scale commercial pilot and early technology adoption.

Commercialization – Market uptake and cost reductions for technology as uptake increases.

Available performance information hindered the evaluation’s assessment of overall results, particularly with respect to the FIP

The FIP (TT program and CWFC) performance reports did not provide clear evidence of overall program progress on key deliverables and outcomes. In addition, an assessment of achievement of outcomes against targets was not possible given that many of the TT and IFIT program targets were ambiguous and reporting against existing targets was inconsistent. Therefore, our evaluation was not able to fully assess the magnitude of progress and impact, particularly with respect to the TT program component.

Outcome Achievement – Findings

The forest sector innovation programs are broadening their reach, but efforts are needed to further expand linkages with small and medium-sized businesses, academia and other sectors

According to the innovation literature, effective collaboration is an essential component of innovation and research programs. The right stakeholders need to be involved to plan, to conduct, to share and to use research results. The literature indicates that SMEs are important to developing transformative technologies, and non-traditional industry partners – including from other sectors (e.g. energy, chemical) – are important to expanding markets, broadening research, and creating an innovation advantage.

Our evaluation found that the various FSI programs are maintaining and strengthening partnerships and networks. Many project files reviewed show involvement of provincial, federal, and forest industry stakeholders. However, efforts are needed to engage smaller companies and other sectors to facilitate a transition towards a forest bioeconomy.

The previous evaluation of the FSI programs contained a recommendation to improve collaboration with SMEs and with non-traditional forest sector partners to facilitate the sector’s transformation. CFS has taken several actions to address this recommendation, but efforts are needed to further broaden reach.

For example, in 2017, NRCan and the Canadian Council of Forest Ministers (CCFM) launched a Forest Bioeconomy Framework. The Framework establishes a path that will result in a forest bioeconomy that uses sustainable biomaterials from healthy forests for high value-added manufacturing; this is intended to be achieved through forest sector innovation, collaboration, and investment. CFS is also working towards a broad bioeconomy strategy for 2019, in coordination with other federal departments and agencies.

About 2/3 of IFIT recipient survey respondents agreed that IFIT helped create or strengthen collaborations between their organization and other stakeholders.

Source: FSI evaluation survey.

Interviewees and documents indicate that science continues to be siloed within CFS, and with FPInnovations, and other federal labs, particularly the National Research Council. However, there have been reported planning and coordination improvements between NRCan and FPInnnovations with respect to bioenergy.

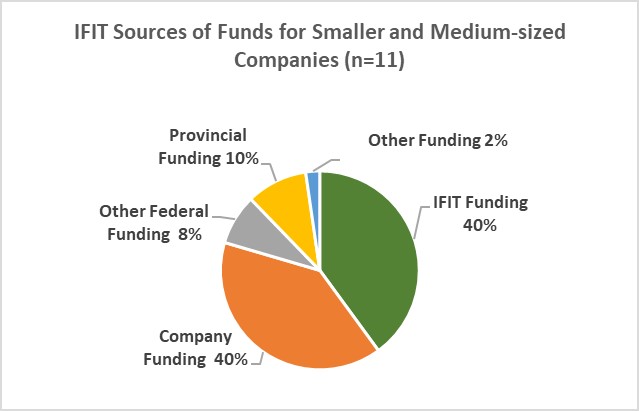

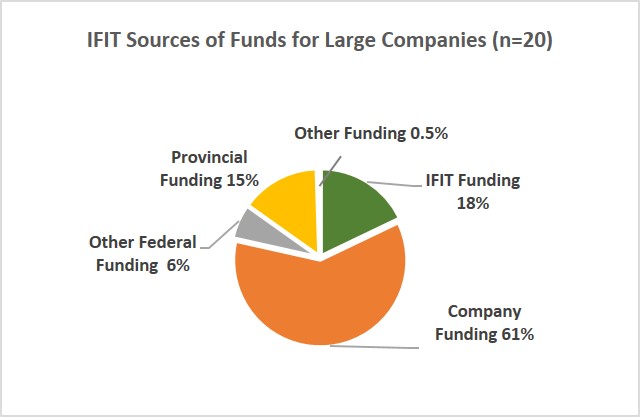

In 2014, IFIT added an additional applicant stream for funding based on company size, which provided a simplified process for smaller companies (i.e., companies with fewer than 100 employees and $50M/year in sales) with lower dollar-value projects. Since then, IFIT project data shows that there has been an increase in the number of SME applications to IFIT. However, an examination of IFIT documentation revealed that only four of the 20 projects funded during this evaluation period had partners from non-traditional sectors.

IFIT has funded a larger proportion of SME costs than those of large companies. Of 20 large company projects, IFIT funded only 18% of the total project costs, while industry provided 61%. As regards 11 projects with SME proponents, IFIT funded 40% of the total costs, and industry provided 40%.

While these design modifications have helped the program reach more SMEs, some interviewees suggest that more extensive outreach targeting other sectors and SMEs is required.

Text version

Description: IFIT Sources of Funds for Smaller and Medium-sized Companies (n=11). A pie chart showing the relative proportion of funding by various sources for the 11 IFIT-supported projects of small and medium-sized companies. Of the total project costs for all 11 projects by small and medium sized companies, 40% was funded directly by the company, 40% was provided by IFIT, 10% provided by provinces, 8% provided by other federal funding sources, and 2% was provided by other sources.

Text version

Description: IFIT Sources of Funds for Large Companies (n=20). A pie chart showing the relative proportion of funding by various sources for the 20 IFIT-supported projects of large companies. Of the total project costs for all 20 projects by large companies, 61% was funded directly by the company, 18% was provided by IFIT, 15% was provided by provinces, 6% provided by other federal funding sources, and 0.5% provided by other sources.

FPInnovations has implemented initiatives to improve reach to SMEs, but its membership structure is perceived as limiting the reach of the TT program

Similar to the previous evaluation, interview, survey and document evidence indicates that FPInnovations membership structure limited the reach of its programs, including the TT program. An analysis of FPInnovations’ 2017-18 industry membership conducted for this evaluation shows that the proportion of memberships of other sectors and smaller firms is limited. Respondents to our survey of industry stakeholders, the majority of which were SMEs, most frequently cited the cost of membership as a key barrier to joining FPInnovations. At the time of this evaluation, FPInnovations was undertaking a review of its membership structure.

To improve its accessibility to SMEs, FPInnovations launched an Associates web-based program in 2015 designed to align with the needs of wood manufacturing SMEs across Canada and to provide quick access to FPInnovations experts and information. However, there is no information in the FPInnovation performance reports as to the extent of use of this program.

There is a need to strengthen collaborations and linkages between FPInnovations and academia.

Academia performs research and development activities in a number of disciplines that are relevant to forest sector transformation. Therefore, it is important to optimize this linkage to ensure sufficient knowledge exchange between the key stakeholder groups.

Example of broad collaboration – Case study of the Thermo-Mechanical Pulping (TMP)-Bio project (TT program)

The TMP-Bio project involved the pilot level scale-up and optimization of a thermo-mechanical pulping process (TMP-Bio) that converts wood chips into renewable biochemicals (e.g. H-lignin) and developing high-value applications and markets for those biochemicals. Lignin, for example, can replace petroleum-based chemicals in a wide range of forest and non-forest sector applications including wood adhesives, polyurethane foams, and thermoplastics.

The case study concluded that the significant collaboration with universities, NSERC research networks and industry (including potential end-users), and coordination with municipal, provincial and other federal funding programs led to an integrated R&D program with support for lab-based research through to pilot plants. For every $1.0 of TT funding, there was $6.5 from other sources. The case study notes that the numerous and varied types of partners and conditions of funding made the project administratively complex, and required about a year to put the arrangement in place.

From 2010 to 2015, university representatives were connected to FPInnovations from the eight forest sector R&D networks that were set up by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). These network grants were awarded to successful applicants for a 5-year period to fund multidisciplinary research projects in research areas that required a network approach.

A few academic stakeholders cited the need for specific funding directed to academic and FPInnovations partnerships and broader networks that include industry. FPInnovations Annual Performance Reports show a decline in 2016-17 in the number of projects involving collaborations with academics. Other suggestions for improving linkages include a sabbatical program for FPInnovations, and work exchanges between FPInnovations and academia.

Regarding CWFC, interview and case study evidence shows good engagement with industry, provinces and academia. Program documents indicate that CWFC regularly collaborates with over 70 stakeholders from across the forest innovation spectrum. Based on CWFC project data, CWFC leveraged $2.5 (includes both funds and in-kind) from other partners for every dollar spent from 2013 to 2016.

CWFC was the leader in the development and establishment of the Assessment of Wood Attributes from Remote Sensing (AWARE) network, an NSERC-led collaborative research and development project for universities, government and industry, which provincial and industry stakeholders describe as a very effective network.

Some external stakeholders noted that CWFC could further broaden its reach to a wider circle of academic and other stakeholders, as well as to provincial representatives at senior management and policy levels. CWFC is currently undertaking various strategies to further strengthen its collaborations. For example, CWFC plans to support the development of a national research initiative (production of resilient forests to respond to climate change issues) to be co-led with FPInnovations and in collaboration with a broad range of stakeholders.

The forest sector innovation programs are advancing knowledge, technologies, and processes

Evidence suggests that the FSI programs have resulted in new or enhanced knowledge, products, processes, and technologies. In addition, the evidence suggests that the programs have resulted in the pilot and commercial scale-up of several technologies, particularly in the areas of biomaterials, advanced building systems, and improved processes and tools aimed at increasing operational efficiencies.

Text version

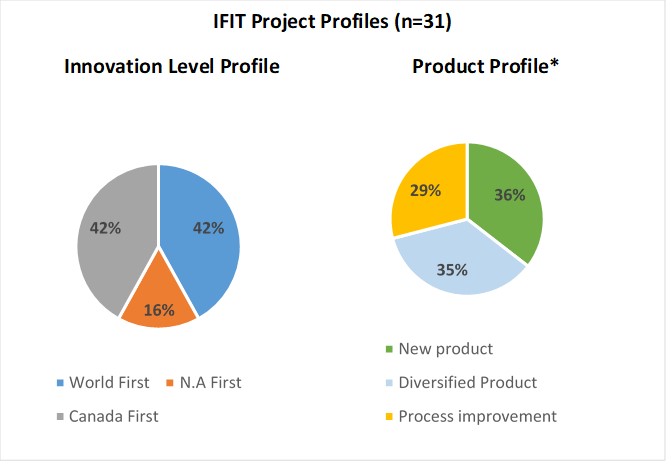

Description: IFIT Project Profiles (n=31). Pie charts showing the distribution of the 31 IFIT-supported projects by innovation level profile and product profile. In terms of the project’s technology innovation level, of the 31 IFIT projects, 42% were world firsts for the supported technology, 42% were the first of their kind in Canada, and 16% were the first of their kind in North America. In terms of the project’s product profile, 36% of IFIT projects focused on producing of new forest sector products, 35% on producing diversified products, and 29% on process improvements.

Evidence indicates that IFIT has supported the scale-up of advanced technologies to a large extent. The following figure shows that a substantial portion of IFIT projects (42%) involve world first innovations and that 36% of IFIT projects have demonstrated the manufacture of non-traditional products.

The evaluation found examples of new technologies and processes produced through the TT program funding. For example, the program component supported the development of multi-functional wood panels, which are able to replace wood-frame walls in construction while not requiring additional insulation, reducing construction costs by 6% to 7%, and shortening construction time by approximately half a day. Similarly, substituting kraft lignin for petroleum-based resin at softwood plywood mills is expected to improve resin efficiency and panel product quality while reducing production costs by $500,000 annually at a 15% replacement rate (substitution rate of lignin), or more than $1M at a 25% replacement rate.

However, given insufficient performance information, it was not possible to assess the extent to which new TT technologies progressed. CFS interviewees note that there are plans to implement a quantifiable measurement scale known as technology readiness levels (TRLs) that will measure how much the technology advances towards commercialization. As of 2018-19, TRLs were not included in TT performance reports.

There have been advancements in bioproducts research, but these advancements have been slower than anticipated

Case study, document, and interview evidence shows progress with respect to improvements in production processes and in developing new applications for novel bioproducts, such as cellulose nanocrystals and lignin-based products. These types of bioproducts are essentially wood fibres that are broken down to the smallest of scales through specialized patented processes. These bioproducts have the potential for a wide variety of applications, including in construction products, aerospace materials, food additives, medical and pharmaceutical applications, and paints and coatings.

Examples of advancements and innovations in bioproduct research

Adhesives: Development and testing of six new “green” wood based adhesives which are now at the technology transfer stage; and commercial application for kraft lignin as an adhesive alternative to petroleum-based synthetic resins (TTP)

Biochemicals: Scaling-up of FPInnovations’ thermo-mechanical pulping process (TMP-Bio) that converts wood chips into renewable biochemicals such as sugar and hydrolysis lignin which is now at the industrial stage of development (TTP)

Pulp: Making dissolving pulp from underutilized birch trees, a North-American first. Dissolving pulp is used to make textiles and clothing, among other things (Fortress Specialty Cellulose Inc. supported by IFIT)

Oil: World’s first commercial facility that converts forest residues into a renewable fuel oil (AE Cote Nord Canada Bioenergy Inc. supported by IFIT)

Case study and interview evidence indicates that while research pertaining to bioproduct applications has progressed, this research has advanced at a slower pace than expected. These delays were attributed to gaps in later stage research directed at developing product applications. Some interviewees also noted the tendency to underestimate the difficulty of moving from research to commercialization, especially for projects involving advanced biomaterials. Some federal, industry and provincial stakeholders perceived that there is an information gap between the developers of niche value-added forest products and intended end-users, and that the sector needs to improve its understanding of the value chain of these products, starting with an understanding of end-user needs.

FPInnovations’ intellectual property (IP) policy was also perceived by industry stakeholders to slow the pace of technology adoption. FPInnovations provides a “black-out period” of three years during which it only provides licenses to its members. In addition, interviewees noted that industry was reticent to become involved in projects if they do not have clear ownership of the IP. FPInnovations has recently revised its IP policy in an effort to improve industry engagement.

FPInnovations research on cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) is considered by experts and stakeholders to be an outstanding technical achievement. CNCs are a natural, recyclable, non-toxic nanomaterial that is extracted from cellulose using a chemical process. CNCs’ unique properties present opportunities for its use in a variety of industrial sectors including forestry, aerospace, oil and gas, and pharmaceuticals. In the past five years, FPInnovations has adopted a more focused research approach, which interviewees and documents indicate has led to more accelerated CNC product development and new partnerships with industry.

The CNC case also illustrates the amount of time needed to adopt novel materials in commercial products (at least 10 years according to experts). One of the key hurdles that FPInnovations, supported by TT funding, overcame was the production of sufficient CNC to facilitate product applications research. The adoption of CNCs also faces significant regulatory and standards-related challenges. As a result, CFS and FPInnovations have focused more effort over time on standards development, not only for CNCs, but also for other biomaterials.

A challenge to market development is the need to work one-on-one with potential end-users to demonstrate the advantages and practicalities of incorporating CNC into existing products. Some external stakeholders noted that ongoing funding for product applications research is needed in addition to capital costs. This type of research was cited as high-risk, time-consuming and resource intensive.

The development and advancement of cellulose nanocrystals (TT program)

In 2006, NRCan’s TT program supported the creation of a small pilot plant at FPInnovation’s lab to produce CNC for research purposes. In 2010, Celluforce, a joint venture between Domtar and FPInnovations, was incorporated and the world’s first pre-commercial demonstration plant was built in 2011 (TT, industry and provincial funding). The plant ceased operations in 2013 due to a lack of market for the produced CNC as well as operational issues. However, it had produced enough CNC to meet demands to conduct further product applications research. Production resumed again in 2019 with funding to support a full commercial demonstration-scale plant.

Achievements of NRCan supported research by FPInnovations during the last 5 years include:

- A new Canadian standard on test methods for characterization of CNCs published in 2014

- Identification of potential CNC applications such as in coatings, thermoplastics, and in drilling fluid for the oil and gas sector (TT and industry funding)

- New shareholders: Schlumberger (large oil and gas service company) and Fibria (Brazilian forestry company now Suzano), and Investissement Quebec

- SDTC and Schlumberger-CelluForce funding to optimize the extraction process of CNC and develop applications for use in oil and gas sector.

- IFIT funding in 2019 (Government of Quebec and industry funding) to support the world’s first full commercial demonstration-scale plant and to attain its production capacity of 300 tonnes per year.

The forest sector innovation programs undertake a variety of knowledge transfer activities, but there remain issues with industry receptor capacity

Document, interview and case study evidence indicates that CWFC, TT, FRII, and IFIT are conducting a range of knowledge transfer activities. Based on a recommendation in the previous evaluation to increase communication of results to enhance likelihood of replication of IFIT projects, IFIT has increased its dissemination efforts. For example, to encourage adoption of IFIT supported technologies by other firms, IFIT has posted project information sheets and fact sheets on technologies “worth replicating”; the extent to which this posted information is used however is not known.

With respect to FPInnovations, industry and other stakeholder members have exclusive access to research reports and publications, tools, guides and manuals, needs analysis, hardware and software solutions and leading-edge technology. Industry members can access a network of experts, and receive free consultations, technical advice, and technical updates.

In addition, knowledge exchange specialists are embedded in FPInnovations and CWFC activities. Most of these activities are done by FPInnovations, but also involve other players such as the Canadian Woodlands Forum, which has access to a large network of industry stakeholders. CWFC also leads regular cross-country meetings with provincial and industry representatives, which stakeholders reported were critical for knowledge exchange and generating interest and commitment for new research and technologies.

However, project document and interview evidence indicates that there is insufficient industry capacity to use the TT program research results. To address this lack of capacity, FPInnovations reports that it has increased its webinars and interaction with industry members.

However, uptake of research, according to interview and case study evidence, not only depends on dissemination activities, but also requires a market pull approach, aligning innovations with end-user needs. The evaluation found examples of effective combination of technology push and market pull approaches – for example advanced buildings systems, as described in the next section of this report.

Forest sector innovation science has contributed to the development of codes and standards, showing the most significant progress in the area of advanced building systems

Document, interview, and case study evidence indicates that the TT program’s research and expertise, as well as FPInnovations’ participation in various code committees, have informed the development of codes and standards largely with respect to advanced building systems and materials. According to interviewees and case study evidence, these efforts facilitate enhanced market access and acceptance of Canadian wood and innovative wood products.

The TT program and the FRII have also informed codes and standards related to engineered wood and other value- added wood products such as the mid-ply wall system, cross-laminated timber (CLT), and prefabricated panels and modules. Many of these products are suitable for use in mid-rise wood frame buildings and other larger commercial buildings combining wood and other building materials. In addition, the Expanding Market Opportunities Program also provides funding to FPInnovations and the NRC for technical research related to advanced building systems.

Interview and documentary evidence indicate that FRII and the TT program’s research on wood durability, preservatives, joints, fire testing, and earthquake design has contributed to changes in the National Building Code of Canada (NBCC) and related standards. This work is often done in collaboration with provinces, the Canadian Wood Council and the National Research Council (NRC). In 2015, the NBCC informed by this research and expertise, introduced prescriptive provisions to allow for mid-rise wood constructed buildings of up to 6-storeys. Various provinces have adopted key elements of the NBCC in their provincial building codes, increasing the allowable number of storeys that can be built from wood from four to six.

Document, interview, and case study evidence indicates that the development of national and international standards for cellulosic nanomaterials and other biomaterials and biochemicals (e.g. lignin) is progressing; however, interviewees note that development of these standards is still in the early stages. FPInnovations research and expertise informed the first Canadian standard developed for the measurement and characterization of cellulosic nanomaterials (i.e., CSA Z5100). Documents report that this served as the basis for Canada to lead on the International Organization for Standardization’s development of a standard for cellulose materials for the characterization of cellulose nanocrystals.

The forest sector innovation programs have informed policy development and forest planning and management decisions

Interview, document and case study evidence suggests that FSI programs are informing forest sector-related management and policy decisions and practice. Documents also indicate that CFS has contributed to knowledge and science advancement related to the bioeconomy, which is expected to contribute to policies and regulations on topics such as biomass availability in Canada, the development of a greenhouse gas (GHG) accounting framework for biomass in Canada, and Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Clean Fuel Standard.

Evidence indicates that FRII, the TT program, and CWFC’s work is also influencing forestry management decisions, practices, and policy development. According to several provincial and industry interviewees, CWFC research, funding, expertise, and coordinating efforts have contributed to forest planning and management decisions at the provincial levels and, to some extent, industrial levels. Case study evidence indicates that enhanced forest inventory techniques have assisted the provinces and the forest industry to manage the forest resource more efficiently, by pointing to high value stands of trees, and allowing them to be harvested more efficiently. Provincial representatives note that CWFC genomics research and expertise has informed their planning decisions. Provincial and industry interviewees and documents suggest that FRII research has had strong influence on transportation policy and practices. For example, FPInnovations’ research has influenced winter weight provincial policies (New Brunswick, Alberta, and Saskatchewan), which allows forest companies to haul heavier loads for longer periods of time.

Other federal government departments and provincial representatives note that access to CFS and FPInnovations expertise informs their own forest sector research and market development programs.

The forest sector innovation programs have resulted in the adoption of research, technologies, and sustainable forestry management practices, but adoption is not yet widespread

More than two-thirds of the IFIT survey respondents agreed that their organization has adopted new technology or processes supported through IFIT. Almost half of FPInnovations survey respondents reported they had adopted a new manufacturing process, and one-third had adopted a technology as a result of FPInnovations

Source: FSI Evaluation Survey

The FSI programs have demonstrated progress towards adoption of novel or value-added innovation products or systems, including:

- Mid-rise wood construction: The number of mid-rise wood-constructed buildings completed has increased to nearly 580 buildings in Canada. This has been facilitated by the NBCC code changes and provincial adoption (Ontario, Quebec, and Alberta) of elements of the national code, allowing an increase in wood frame buildings from four to six storeys.

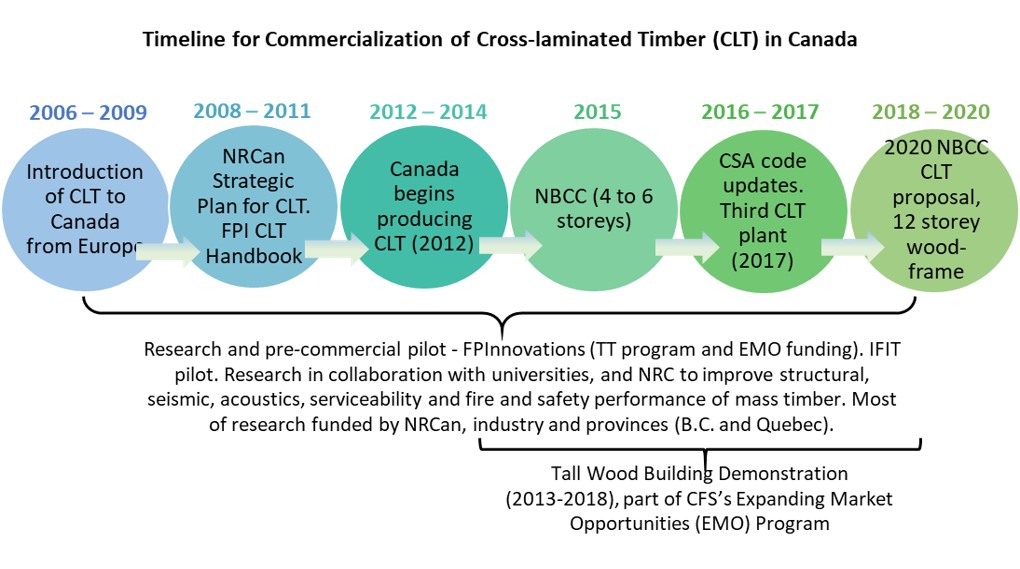

- Cross-laminated timber: The program facilitated commercial production of cross-laminated timber in Canada through research, pilot plant support, research for the development of related codes, and the creation of guidance manuals for industry use. However, the manufacturing supply of CLT continues to be limited in Canada.

- Enhanced Forest Inventory: The programs have resulted in provincial and industry uptake of enhanced forest inventory tools and practices.

Interview, survey and case study evidence indicates that adoption of incremental and process innovations is occurring. Industry stakeholders and survey respondents frequently reported the implementation of techniques to optimize mill energy use, manufacturing, harvesting, transportation, operational efficiencies, and safety. However, the extent to which these innovations have been implemented is unclear.

Evaluation evidence suggests that IFIT supported technologies have not yet been widely adopted by other companies. Many interviewees and survey respondents indicate that it is generally too early for the achievement of this outcome. The 2015 IFIT-commissioned study on the replicability potential of IFIT projects as well as later analysis identified 15 IFIT projects that have good potential for replication. Our evaluation’s survey of industry stakeholders also shows replication potential of IFIT projects, as more than half of our survey respondents that received IFIT funding indicated that other companies have expressed an interest in replicating the technology. Interviewees noted barriers to replication such as the inability of novel products to compete with existing products in terms of demonstrated performance, quality, or cost advantages (e.g. cost of producing products is comparatively high).

Text version

Description: Timeline for the Commercialization of Cross-laminated timber (CLT) in Canada. Graphic showing the timeline of major milestones for the commercialization of cross-laminated timber (CLT) in Canada from 2006 to 2020. From 2006 to 2009, CLT was introduced to Canada from Europe. From 2008 to 2011, NRCan developed a Strategic Plan for CLT, and FPInnovations created the CLT Handbook. From 2012 to 2014, Canada began producing CLT. In 2015, the National Building Code of Canada was updated to increase the permissible height of wood construction from four to six storeys. From 2016 to 2017, the Canadian Standards Association updated its codes. In 2017, the third CLT plant was constructed in Canada. Since 2018 until 2020, work has been underway to update the National Building Code of Canada to increase the permissible height of tall wood-frame buildings to 12 storeys, reflecting advancements in CLT. Since 2006, research and pre-commercial pilots for CLT have been undertaken by FPInnovations using funding from the TT Program and the Expanding Market Opportunities Program. IFIT has also supported pilots. Research was also conducted in collaboration with universities and the National Research Council to improve structural, seismic, acoustic, serviceability, and fire and safety performance of mass timber. Most of the research has been funded by NRCan, provinces (BC and Quebec), and industry. From 2013 to 2018, the Expanding Market Opportunities Program also supported the Tall Wood Building Demonstration Initiative.

The Story of Cross-laminated Timber

Cross-laminated timber (CLT) is a large structural, prefabricated, solid engineered wood panel product composed of multiple layers of dimension lumber held together with adhesives. CLT has a wide variety of applications including its structural use in multi-story buildings. While there is no specific production data available for CLT, there are three plants in Canada producing CLT. However, interviewees note that the Canadian manufacturing supply of CLT is limited.

The FSI programs, in collaboration with other innovation partners, have contributed to the introduction and commercialization of CLT in Canada in the following ways:

- Through support of the TT program, provided technical input for codes and standards

- R&D on seismic design, fire testing, durability, serviceability research

- CLT technical guides for builders and designers; and

- IFIT support for manufacture of a new CLT product – the EcoStructure Wall System, an alternative to concrete walls.

In terms of adoption, CWFC has made reported gains with respect to their work on enhanced forest inventory. As of 2019, more than 30 million hectares of forest cover have LiDAR coverage, representing almost 10% of Canada’s forest cover. More than 50 million hectares is in the planning or proposed stages for LiDAR acquisition. Interest and uptake have been particularly strong in Atlantic Canada, Alberta, Quebec and Ontario. Provinces and industry representatives report that CWFC has strongly influenced uptake by contributing research and expertise; by supporting various test sites across the country; by playing a strong brokering and coordination role; and through its knowledge exchange activities.

Municipal sewage waste treatment and wood biomass production (CWFC)

CWFC has been working since 2006 to create a short rotation wood crop model that is suitable for use in North America. In coordination with the province of Alberta and various municipalities, a number of demonstration sites were established to show how treated municipal waste can be safely used to irrigate and fertilize short rotation woody crops, such as willow trees. This wood biomass can then be used for heat or potentially higher-value products.