Evaluation of the Nuclear Legacy Liabilities Program (NLLP)

Acronyms

AECL: Atomic Energy Canada Limited

CRL: Chalk River Laboratories

CNL: Canadian Nuclear Laboratories

CNSC: Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission

EVMS: Earned Value Management System

FPS: Fuel Packaging and Storage Project

GoCo: Government-owned, Contractor-operated

HEU: Highly Enriched Uranium

IAEA: International Atomic Energy Agency

MOU: Memorandum of Understanding

NLLP: Nuclear Legacy Liabilities Program

NRCan: Natural Resources Canada

NWMO: Nuclear Waste Management Organization

R&D: Research and Development

RFP: Request for Proposal

SLWC: Stored Liquid Waste Cementation project

SMAGS: Shielded Modular Above-Ground Storage

TBS: Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

URL: Underground Research Laboratory

Executive Summary

This report presents the findings, conclusions and lessons learned of the evaluation of the Nuclear Legacy Liabilities Program (NLLP). The evaluation assessed the relevance and performance (effectiveness, efficiency and economy) of the NLLP over the six-year period from 2009-10 to 2014-15, during which time the program oversaw approximately $869.5 million in Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) expenditures.

The NLLP was established in June 2006 to safely and cost-effectively control and reduce risks and liabilities at AECL sites based on sound waste management and environmental principles in the best interests of Canadians. The nuclear legacy liabilities included outdated and unused research facilities and associated infrastructure, accumulated radioactive waste, and contaminated lands located at AECL sites in Ontario, Manitoba, Quebec and Nova Scotia.

The approach taken to meet these objectives was to improve waste management practices and carry out infrastructure decommissioning and environmental restoration projects while advancing and refining the long-term strategy. At the same time, necessary care and maintenance activities continued in order to maintain the liabilities in a safe state.

In delivering the NLLP, NRCan’s Energy Sector provided policy direction and oversight. It oversaw implementation and public engagement activities related to the NLLP. Atomic Energy Canada Limited (AECL), as the proponent (implementer) and licensee, identified priorities and developed plans, and delivered activities related to compliance, decommissioning and environmental restoration, waste management, advancing the long-term strategy, and stakeholder and aboriginal relations at AECL sites and facilities in Ontario (Chalk River Laboratories, Nuclear Power Demonstration Reactor, and Douglas Point Reactor), Manitoba (Whiteshell Laboratories), Québec (Gentilly-1 Reactor), and Nova Scotia (site of former Heavy Water Plant in Glace Bay).

The evaluation triangulated among various sources of evidence to enhance the reliability of the conclusions drawn from the findings and to formulate the lessons learned in relation to an assessment of the relevance and performance (effectiveness, efficiency and economy) of the NLLP. The evaluation was based on a literature and document review, 14 key informant interviews with 16 individuals and 4 case studies. A subject matter expert was also engaged to provide insight on the planning, validation, and interpretation of the information collected through each line of evidence.

Relevance

There was a clear need for the NLLP, as contaminated lands and infrastructure represent social and environmental risks, and are a liability that has been included in the national accounts. The activities of the NLLP were in line with Canada’s Radioactive Waste Policy Framework, as well as the conclusions of the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) and the Auditor General of Canada, and good international practice, as documented by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), for the management and decommissioning of nuclear facilities.

Activities of the NLLP were also aligned with NRCan roles and responsibilities, and were consistent with AECL’s mandate. The NLLP was designed to address the contaminated lands and infrastructure under AECL’s responsibility, and so mitigate the related social and environmental risks.

Performance - Efficiency and Economy

The efficiency and economy of various aspects of the NLLP was assessed, including governance, the delivery model, financial management, risk analysis and cost estimation, waste management, and project management.

Governance of the NLLP appeared adequate, as a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) delineated roles and responsibilities, and oversight was provided by a Joint Oversight Committee, an ADM-level Steering Committee, and an internal AECL NLLP Board. There was a perception among many AECL key informants that despite efforts to reduce reporting burden and provide real-time updates, certain aspects of the governance structure increased administrative and reporting burden.

A matrix approach for resource sharing between AECL branches caused competition for resources, delays, and impeded the ability to secure qualified human resources on some projects. Other projects had direct control of their resources, and did not experience those impacts. The ability to outsource work and hire staff was restricted during the last few years of the program to avoid potential conflicts with the Government-owned, Contractor-operated (GoCo) procurement process. Despite the full implementation of an action plan to update AECL’s procurement strategy, AECL’s expectations on the level of risk to be assumed by contractors may have sometimes contributed to bids that were higher than expected and in at least one case, to an extension of the bid period to revisit the balance of risk to be borne by the contractor and the federal government. The program increased expenditures for third-party contracts to engage the needed external expertise (e.g., waste management and decommissioning), although some AECL and external informants felt the decision-making process, especially planning, would have benefitted from greater use of international expertise.

The planning and budget-setting processes were adequate, with a small spending lapse of roughly 1% of the total budget over six-years, due in part to an MOU provision to allow carry forwards of unspent funds. Although a number of informants felt more use should have been made of financial incentives to complete work more quickly, NRCan key informants noted these would not have been practicable due to AECL’s limited procurement capacity, and possible interference with the GoCo procurement process.

The current evaluation found that risk analyses were conducted at multiple levels, including via AECL’s Strategic Planning and Project Risk Registers, and an Integrated Risk Management Framework. As well, AECL applied a staged decision-making process to assess projects’ value for money, and was required to develop lifecycle cost estimates prior to starting a project. To avoid constraining the GoCo contractor in implementing innovative and cost-effective long-term solutions, no new major projects were initiated as of 2013, which limited the need for cost-effectiveness analyses. However, some AECL key informants were still of the opinion that AECL should have conducted cost-benefit analyses for more projects.

In the absence of long-term radioactive waste management or disposal facilities, the NLLP was responsible for advancing plans for long-term management facilities for AECL’s legacy low-level and intermediate-level radioactive waste. In keeping with the requirements of the approval for the second NLLP funding period, AECL developed an integrated waste disposal strategy as part of an update to the liability cost estimate in 2013. However, it was decided to defer decision making on the radioactive waste management facilities, to avoid imposing constraints on the GoCo. While it was recognized that this delay could result in increased overall costs and reduce cost efficiency (i.e., additional moving, storage, and packaging costs), there was also a potential for the GoCo contractor to propose solutions that would result in overall savings.Footnote 1

AECL implemented an Earned Value Management System (EVMS) in 2013 to better evaluate project progress against budget and schedule, although the information to support EVMS varied considerably from project to project at the time the NLLP ended. AECL informants noted that AECL’s project management system was appropriate for reporting, although not user-friendly for daily use.

AECL also initiated the development of an integrated waste inventory database in 2014 to store both historic waste information, comprehensive data for recently produced waste, and the findings of legacy waste characterization initiatives.

Performance – Effectiveness

The achievement of program milestones was the main measure of program performance against plans and commitments. For the three-year funding period from April 2011 to March 2014, 78 of 84 planned milestones (93%) were completed,Footnote 2 and 51 of the 54 (94%) milestones due in fiscal 2014-15 were completed by the end of March 2015. This represents a significant improvement over the milestone completion rate of 67% (91 of 136 milestones) for the five-year start-up phase (April 2006 to March 2011) of the NLLP.

Taken together, the different lines of evidence demonstrated that the NLLP made progress toward its expected immediate and intermediate outcomes. Specifically:

- NLLP delivery emphasized improved health, safety and environmental conditions at sites to satisfy regulatory requirements. All completed projects met regulatory requirements, and this was reflected in the achievement of the vast majority (i.e., over 90%) of planned milestones related to removing buildings and infrastructure, legacy waste management, and site remediation.

- Improvements to legacy waste management were observed through waste clearance (at Chalk River and Whiteshell Laboratories), the shipment of legacy waste to the United States for volume reduction or disposal, and HEU repatriation. Progress was also made on the FPS and SLWC projects.

- It was generally felt that strategic decisions guided NLLP implementation toward risk and liability control by focussing on higher-risk infrastructure. A number of examples that risks have been reduced were documented in the evaluation, and NRCan informants noted that the liability reduction resulting from the implementation of the NLLP was taken into account annually as part of the update to the liability cost estimate in the Public Accounts. In retrospect, and despite that no such requirement was imposed by the Treasury Board, the absence of targets made it difficult to quantify risk reduction in the context of the current evaluation.

- The program supported better costing and an increased understanding of the liabilities through improved waste and site characterization data to support risk and cost estimates, changes in decommissioning plans, and the advancement of decommissioning work. Also, the liability cost estimate was adjusted to account for an increased attribution of indirect costs (e.g., corporate support costs and operating costs for the CRL site) to the NLLP.

- Finally, mechanisms were developed as a means for stakeholders and Aboriginal groups to be aware of and provide input to the program. Representation from Aboriginal groups was included on the Environmental Stewardship Council, a Communication Plan was developed, and the CNSC was satisfied with efforts to keep the public informed of and disclose activities at CRL. However, a conscious decision was made in 2010 not to pursue the intermediate outcome “Public confidence in and support for the long-term strategy” to avoid imposing constraints on the GoCo contractor.

Lessons Learned

Based on the evaluation findings, the following lessons were learned:

- Multiple accountabilities create challenges for program oversight.

Under the NLLP, NRCan had ultimate responsibility for the program, but did not have the authority to set program priorities for AECL, because AECL owned and was ultimately responsible for the waste liabilities. The GoCo management model addresses these challenges in that AECL has full latitude to set priorities and objectives for its GoCo contractor to achieve reductions of risks and liabilities. Further, as a Crown corporation, AECL delivers on its mandate and missions at arms-length from the Government of Canada, and so can leverage private sector capacities to implement an innovative, timely and cost-effective program of work to meet AECL’s objectives. - Potential efficiencies of matrix resource allocations can be offset by delays resulting from a competition for resources.

Competition for resources at Chalk River Laboratories affected the delivery of the NLLP, as key resources, such as engineering, radiation protection specialists, procurement and trades were managed on a matrix basis, and shared between site operations, research and development, commercial business, and decommissioning and waste management. While dedicated project teams were established to advance key projects, such as HEU repatriation and FPS, other NLLP projects and activities had to negotiate for resources with the other site missions on an ongoing basis to deliver on milestones and advance work. Competition for resources was not an issue at Whiteshell Laboratories, as all staff were dedicated to the decommissioning and closure of the site, and the General Manager responsible for the site worked closely with his management team to ensure that available resources were assigned to maximize delivery of NLLP milestones and near-term and long-term plans. - To meet the objectives of large, technically complex programs, there is a constant need to assess and reassess capabilities and capacities.

The NLLP involved a significant investment that AECL was not in a position to manage without significant capacity building. Over its nine-year duration, AECL undertook many initiatives to assess and strengthen its capacity to implement the NLLP, including: hiring staff and engaging contractors with international experience on large-scale decommissioning and waste management projects; entering into cooperation agreements with sister organizations in the United Kingdom, the United States, France and Spain to share best practices and lessons learned; and conducting and participating in numerous internal and external Program reviews. While these efforts resulted in notable improvements and significant progress, they were not sufficient to ramp up AECL’s capabilities and capacities to deliver fully on NLLP objectives. - The achievement of broader Government of Canada objectives may require a re-alignment of program objectives and suspension of activities.

The NLLP was implemented in the context of AECL restructuring for approximately half of its nine-year existence. During this period, adjustments were made to program delivery to support the Government of Canada’s overall objective of engaging the private sector to bring rigour, innovation and cost-effective approaches to the management of the legacy liabilities. During this transition period, AECL continued to implement projects and activities already underway, and added new projects and initiatives to prepare for the transition to the GoCo management model, including the implementation of modern waste inventory and environmental data tracking systems; further characterizing disused facilities, waste burials and contaminated lands; and advancing decommissioning plans for disused infrastructure. While adopting new program objectives related to transition, NRCan and AECL management decided to defer NLLP projects aimed at advancing longer-term intended outcomes. In particular, projects to establish long-term waste management facilities required to effectively deal with the waste were not advanced, in order to avoid actions that could constrain the GoCo contractor in implementing innovative, timely and cost-effective solutions.Footnote 3

Acknowledgments

The Evaluation Team would like to thank those who contributed to the Evaluation of the Nuclear Legacy Liabilities Program, particularly members of the Uranium and Radioactive Waste Division, as well as others who provided significant insights and comments to this evaluation.

The evaluation project was managed by Olive Kamanyana, with support from Amélie Veillette, Barthelemy Pierrélus and Edmund Wolfe. Jennifer Hollington, Glenn Hargrove, Mark Pearson, Gavin Lemieux, and William Blois provided Senior Management oversight. Evaluation services were provided by Goss Gilroy Inc.

Introduction

This report presents the findings, conclusions and lessons learned of the evaluation of the Nuclear Legacy Liabilities Program (NLLP). Canada’s nuclear liabilities resulted from the development of nuclear technology to support Cold War initiatives and nuclear research and development (R&D) related to medicine and to electrical power production. More than one-half of Canada's nuclear legacy liabilities are a result of Cold War activities undertaken between the 1940s and the early 1960s. The remaining liabilities stem from R&D for nuclear reactor technology, the production of medical isotopes, and national science programs conducted by the National Research Council (1944 to 1952), the Department of National Defence and by Atomic Energy of Canada Limited (AECL) from 1952 to present.Footnote 4

Prior to 2006, AECL received funding directly from Treasury Board and was responsible for both the oversight and implementation of decommissioning and waste management work at its sites. Since 2006, the Nuclear Legacy Liabilities Program (NLLP) was under the management of Natural Resources Canada’s (NRCan) Assistant Deputy Minister of the Energy Sector, until the Government-owned, Contractor-operated (GoCo) management model was adopted in 2015. Under the GoCo model, the liability ownership, funding control and oversight functions have been fully separated from site operation and program implementation responsibilities, and the private sector is fully engaged in the work through contractual arrangements.

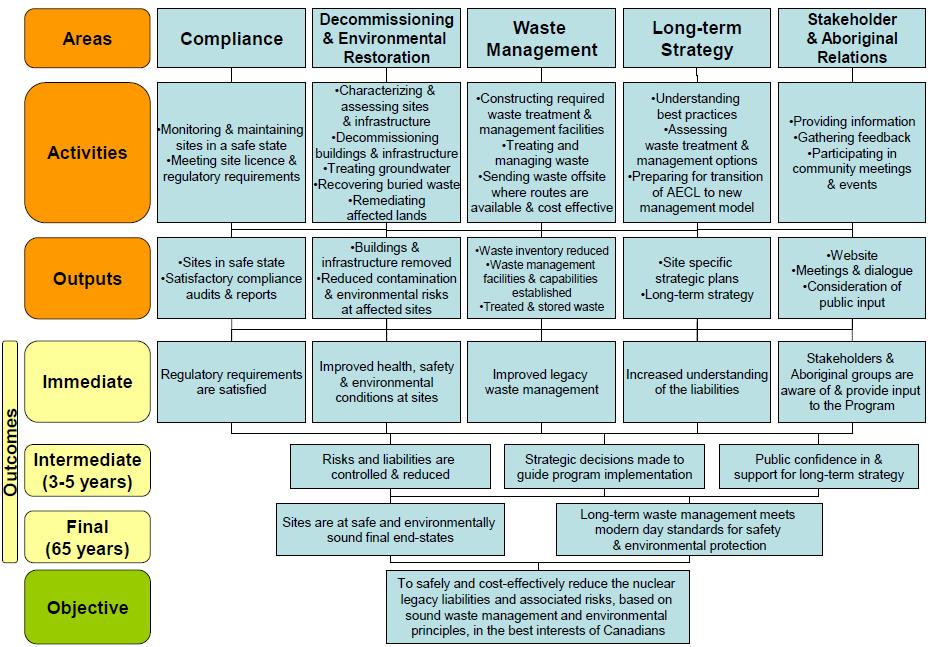

The NLLP was initiated in 2006 to manage the nuclear legacy liabilities by funding Atomic Energy of Canada Limited (AECL)Footnote 5 projects and activities that controlled, reduced and managed the Government’s decommissioning and radioactive waste liabilities. NRCan and AECL were jointly accountable for the implementation of the NLLP. NRCan was responsible for policy direction and oversight, including the control of funding. AECL, as the proponent and licensee, was responsible for ensuring regulatory compliance, identifying priorities and developing plans, building and infrastructure decommissioning, environmental restoration, waste management through waste disposal and treatment, and all other activities in support of the long-term strategy for addressing legacy radioactive waste and decommissioning liabilities at AECL sites. The nuclear legacy liabilities include outdated and unused research facilities and associated infrastructure, accumulated radioactive waste, and contaminated lands located in Ontario (Chalk River Laboratories, Nuclear Power Demonstration Reactor, Douglas Point reactor), in Manitoba (Whiteshell Laboratories) and in Québec (Gentilly-1 reactor)Footnote 6. The NLLP involves activities, processes and techniques in five areas, which together are expected to contribute to the outcomes described in the logic model under Appendix A:

- Compliance: Monitoring and maintaining sites in a safe state, and meeting site license and other regulatory requirements.

- Decommissioning & Environmental Restoration: Characterizing and assessing sites and infrastructure, decommissioning buildings and infrastructure, treating groundwater, recovering buried waste, and remediating affected lands.

- Waste Management: Constructing required waste treatment and management facilities, treating and managing waste, and sending waste offsite where routes are available and cost-effective.

- Long-term Strategy: Understanding best practices, assessing waste treatment and management options, and preparing for transition of AECL to the new management model.

- Stakeholders and Aboriginal relations: Providing information and gathering feedback from stakeholders, and participating in community meetings and events.

Other stakeholders were also involved in the NLLP’s delivery. The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) implements key legislation, such as the Nuclear Safety and Control Act, and Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012, for which the NLLP must be compliant. Global Affairs Canada supported Canada’s relations with the U.S. (Department of Energy - US DOE) for the repatriation of spent HEU fuel and liquid HEU target residue material to the U.S. The Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO) was necessary for advancing the NLLP long-term solutions, in anticipation of eventually sending AECL’s fuel waste for disposal in NWMO’s planned deep geological repository. NLLP delivery was also expected to depend on other key external stakeholders, including multiple external contractors and suppliers for decommissioning, site restoration and waste management projects, as well as ongoing care and maintenance activities (additional descriptive information is provided under Appendix B).

Objectives and Methodology

Evaluation Objective and Scope

The objective of this evaluation was to draw lessons learned from the NLLP’s implementation through the assessment of its relevance and performance (effectiveness, efficiency and economy) over a six-year period from 2009-10 to 2014-15, and up to the time the GoCo management model was launched in September 2015. During the six-year period, the NLLP oversaw approximately $870 million in NRCan expenditures. An evaluation of the first three years of the program (2006-07 to 2008-09) was completed in 2011.

In view of the sixty-five-year time frame for achievement of the final program outcomes (see Appendix A), the analysis of program effectiveness (i.e., the degree to which the program is making progress toward its intended outcomes) was limited to a consideration of immediate and intermediate outcomes.

Evaluation Methods

The evaluation triangulated among various sources of evidence to enhance the reliability of conclusions and lessons learned. The evaluation was based on literature and document review, key informant interviews and case studies. A subject matter expert provided insight on the planning, validation, and interpretation of information collected through each line of evidence described below.Footnote 7

Literature and Document Review

NRCan and AECL documentation was used to address most of the evaluation issues. Documents and reports were provided by the program and other stakeholders, as well as gathered through the Internet. Documentation reviewed included NLLP planning documents, NLLP annual reports from the previous five years and the latest NLLP closeout report (2015). Literature was reviewed to identify the general principles and approaches used for nuclear decommissioning, including success factors for decommissioning and best practices.

Key Informant Interviews

Interviews were conducted with a variety of NLLP management, staff and stakeholders (i.e., key informants) using a semi-structured interview guide. The key informant interviews allowed the evaluation team to assess the relevance, efficiency of the governance and delivery model, and the effectiveness of various NLLP activities in achieving expected outcomes. Fourteen (14) interviews were conducted with sixteen (n=16) individuals. Results of these interviews were also used to inform the case studies. Participants in the interviews included:

- NRCan program managers and management (n=4);

- AECL staff and management (n=10);

- A representative of the CNSC (n=1); and

- A private sector representative (n=1).

Where appropriate to do so, feedback from the CNSC and private sector interviewees are aggregated and reported together as the views of “external” stakeholders.

Key informants were selected in consultation with NRCan and AECL staff. The selection was made to include the views of a number of key NRCan staff, AECL staff and other stakeholders, many of whom were involved in the delivery of the program. The number of respondents was deemed sufficient to address the evaluation issues given the scope of the evaluation. Interviews were conducted in-person or by telephone in either Ottawa or Chalk River.

Case Studies

Four case studies were undertaken based on a review of documentation and feedback from NRCan and AECL staff, as well as other key stakeholders. Selected projects for case studies covered the two largest sites in Chalk River and Whiteshell areas, where approximately 90% of NLLP waste liabilities are located. In addition, projects were selected for their scope within the five NLLP areas of activities, as well as for their materiality to allow better identification of best practices and lessons learned. The following projects were selected in consultation with NRCan and AECL staff (See Appendix C for a detailed description of each project):

- Underground Research Laboratory (Whiteshell);

- Fuel Packaging and Storage (FPS) Facility (Chalk River);

- Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) Repatriation project (Chalk River);

- Stored Liquid Waste Cementation (SLWC) Project (Chalk River).

To maximize the quality and usefulness of the case studies, an iterative approach was used. The evaluation team first used available documentation about the case studies (e.g., CNSC documents, project charters/plans, budgets, requests for proposals and contracts, activity reports, final reports) to gain a better understanding of the projects. After reviewing available documentation, the evaluation team conducted interviews with the AECL managers of the projects. These interviews provided an overall view of the project, as well as evidence associated with all evaluation issues. Case study reports were developed, and validated by AECL staff who were involved in the projects’ management.

Findings

Relevance

Key Findings:

The NLLP is well aligned with federal priorities, and roles and responsibilities, as demonstrated by its alignment to Canada’s Radioactive Waste Policy Framework, NRCan’s Program Alignment Architecture, and NRCan’s second Strategic Outcome.

The NLLP responded to well documented needs to safely decommission infrastructure, remediate contaminated lands, and develop and implement long-term solutions for managing radioactive waste. The NLLP was also consistent with international practice, which suggests that operation and decommissioning of nuclear facilities and activities be managed in a way that keeps people and the environment safe over long periods.

Alignment with Federal Government’s Priorities and Roles & Responsibilities

The NLLP was well aligned with federal priorities, and roles and responsibilities. The program’s objectives (to safely decommission disused infrastructure, remediate contaminated lands to meet federal regulatory requirements, and implement long-term solutions for managing radioactive waste) directly supported the Government of Canada’s radioactive waste and decommissioning responsibilities,Footnote 8 as described by Canada’s Radioactive Waste Policy Framework. This framework states that the owners of radioactive waste are responsible for the funding, organization, management, and operation of disposal and other facilities required for their waste.Footnote 9

The NLLP aligned with NRCan’s 2014-15 Program Alignment Architecture under sub-program 2.3.4 “Radioactive Waste Management”, which in turn contributes to NRCan Strategic Outcome 2: “Natural Resource Sectors and Consumers are Environmentally Responsible.” Natural Resources Canada’s 2014-15 Departmental Performance Report also identifies a departmental objective as enabling government departments, regulatory bodies and industry to assess the impacts of past, present and future natural resource development, and to develop, monitor and maintain resources or clean up wastes responsibly.Footnote 10

Need for Radioactive Waste Management

The waste and contamination situation is a recognized liability that appears in the Public Accounts of Canada and AECL's balance sheet.Footnote 11 Contaminated lands and infrastructure at AECL sitesFootnote 12 (Chalk River Laboratories in Ontario; Whiteshell Laboratories in Manitoba; Nuclear Power Demonstration Reactor in Ontario; Gentilly-1 reactor in Quebec; and Douglas Point reactor in Ontario) need to be safely decommissioned to meet federal and international regulatory requirements; and appropriate long-term solutions need to be developed and implemented for the resulting waste management.Footnote 13 The NLLP responds to a December 2000 Auditor General report and the CNSC call for a strategic, proactive and funded approach for reducing risks associated with nuclear legacy liabilities at AECL sites, including spent fuel, buildings, equipment and waste areas. According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the World Bank, abandoning a facility after cessation of operations is not an acceptable alternative to decommissioning as they could degrade and potentially present an environmental hazard in the future.Footnote 14 High-level nuclear waste is also known to be hazardous for hundreds of thousands of years.Footnote 15 Literature review shows that the trend around the world is to accelerate decommissioning work, in recognition of the fact that delaying work placed a burden on future generations, as it is known that it takes decades for natural attenuation to reduce the environmental hazards from mid- and low-level wastes that have been released into the environment from AECL-managed sites.Footnote 16 Key informants were of the view that Government of Canada funding was needed to address the nuclear legacy liabilities, as they were not covered by AECL’s ongoing government funding to operate the labs and carry out R&D.

In 2003, NRCan undertook, in conjunction with AECL, an initiative to develop a framework for dealing with the legacy liabilities. The initiative encompassed the waste inventory as well as an overall strategy to deal with the wastes including costs, governance, and next steps. NRCan and AECL compiled the inventory and developed a strategy for reducing risks and liabilities over a 70-year period based on sound waste management and environmental principles. AECL’s estimated cost in 2005 to implement the strategy over 70 years was $6.8 billion (2005 dollars).Footnote 17 In 2006, the Government of Canada enabled the implementation of the strategy with the launch of the NLLP, under the responsibility of NRCan and AECL. While AECL was the implementing agency for the NLLP, NRCan was responsible for policy direction and oversight, including control of funding. In 2011, bearing in mind the upcoming AECL restructuring, the NLLP was renewed for a three-year second phase that ended March 31, 2014. For the fiscal year 2014-15, and again for 2015-16, the NLLP was extended with additional funding to cover the period until AECL restructuring was completed in September 2015.

Performance - Efficiency and Economy

Key Findings:

Governance mechanisms for the NLLP appear to have been adequate, as the roles and responsibilities of NRCan and AECL were outlined in a Memorandum of Understanding, a Joint Oversight Committee was established, strategic oversight was provided by an Assistant Deputy Minister Steering Committee, and AECL established an internal NLLP Board for decision-making. The Assistant Deputy Minister Steering Committee was established in 2012 in response to a 2011 Evaluation recommendation that NRCan should enhance its oversight of the NLLP. AECL representatives noted that while generally effective, the Assistant Deputy Minister Steering Committee was not transformational or strategic. NRCan informants noted that transformational change was occurring as a result of the AECL restructuring process, and that a key area of focus for the Steering Committee was to navigate the NLLP through the transition. This was reflected in the Terms of Reference for the committee, which focused on the strategic oversight of the Program. As well, despite efforts to reduce reporting burden and provide real-time updates, there was a perception among most AECL key informants that the committees continued to generate a significant amount of reporting burden.

The joint NRCan-AECL delivery model delineated roles and responsibilities. A matrix approach for resource sharing between AECL branches caused competition for resources, delays, and impeded the ability to secure qualified HR for some projects. Other projects had direct control over their resources, and did not experience these impacts. The ability to outsource work and hire staff was also restricted during the last few years of the program to avoid potential conflicts with the incoming GoCo model. Despite the full implementation of an action plan to update the AECL’s procurement strategy, procurement issues persisted, and resulted in delays for some projects. The program also demonstrated a large increase in expenditures to engage the needed external expertise (e.g., waste management and decommissioning), although some AECL and external informants felt the decision-making process, especially planning, would have benefitted from greater use of international expertise.

The planning and budget-setting processes were adequate, with a small spending lapse of roughly 1% of the total budget over six-years, due in part to an MOU provision to allow carry forwards of unspent funds. Although a number of informants felt more use should have been made of financial incentives to complete work more quickly, NRCan key informants noted these would not have been practicable due to limited procurement capacity, and possible interference with the GoCo procurement process.

The current evaluation found that risk analyses were conducted at multiple levels, including via AECL’s Strategic Planning and Project Risk Registers, and an Integrated Risk Management Framework. As well, AECL applied a staged decision-making process to assess projects’ value for money, and was required to calculate cost estimates prior to starting a project. To avoid constraining the GoCo contractor in implementing innovative and cost-effective long-term solutions, no new major projects were initiated as of 2013, which limited the need for cost-benefit analyses. Some AECL key informants were of the opinion that AECL should have conducted cost-benefit analyses for more projects.

In the absence of long-term radioactive waste management or disposal facilities, the NLLP was responsible for advancing plans for long-term management facilities for AECL’s legacy low-level and intermediate-level radioactive waste. In keeping with the requirements for the second NLLP funding period, a long-term integrated waste strategy was developed as part of an update to the liability cost estimate in 2013. However, it was decided to defer decision making on the radioactive waste management facilities, to avoid imposing constraints on the GoCo. This delay was expected by some to increase overall costs and reduce cost efficiency (i.e., additional moving, storage, and packaging costs).

AECL implemented an Earned Value Management System (EVMS) in 2013 to better evaluate project progress against budget and schedule, although the information to support EVMS varied considerably from project to project at the time the NLLP ended. AECL key informants noted that AECL’s project management system was appropriate for reporting but not user-friendly. AECL also initiated the development of an integrated waste inventory database in 2014 to store both historic waste information, comprehensive data for recently produced waste, and the findings of legacy waste characterization initiatives.

Governance Structure

A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between NRCan and AECL, signed in 2006, set out the respective roles and responsibilities and the overall framework for the two organizations to work together to implement the NLLP. Under the MOU, a Joint Oversight Committee of NRCan and AECL representatives was established to make consensual decisions on the planning, delivery, reporting and administration of the NLLP.Footnote 18 The 2011 evaluation of the NLLP recommended that NRCan enhance the oversight of the NLLP. The key measure implemented to address this recommendation was to create an Assistant Deputy Minister-level Steering CommitteeFootnote 19 to strategically oversee the work of the Joint Oversight Committee. For its part, in the fall of 2011 AECL established an internal NLLP Board with the mandate of being the Nuclear Laboratories’ main decision-making body for the management and execution of the NLLP.

The ADM-level Steering Committee provided a forum for senior NRCan, AECL and CNSC management responsible for the NLLP and AECL restructuring to meet semi-annually to provide strategic oversight, and discuss corporate-level matters and issues affecting the NLLP delivery. AECL representatives provided mixed views about the Steering Committee. A few mentioned that the committee was generally effective, improved over time and that it was needed in the context of the transition to the GoCo governance model. A few also mentioned, however, that the committee played mostly a monitoring role and was not transformational or strategic. Their view was that there were too many layers and the governance structure did not address some of the barriers faced by NLLP, including disposal facilities for the waste. NRCan informants noted that transformational change was occurring as a result of the AECL restructuring process, and that a key area of focus for the Steering Committee was to navigate the NLLP through the transition. This was reflected in the Terms of Reference for the committee, which focused on the strategic oversight of the Program.

Both the NRCan internal audit (2010) and evaluation (2011) of the NLLP identified a need to streamline reporting requirements, and recommended that NRCan and AECL establish an approach to increase value and reduce reporting burden. The audit also recommended that NRCan work with AECL to establish an approach for reporting on progress that provided real-time updates. In early 2012, NRCan and AECL revised requirements for quarterly reports such that comprehensive progress reports were produced semi-annually and shorter, higher-level progress reports were produced for the intervening quarters.Footnote 20 Despite these efforts, the current evaluation found that concerns about reporting burden persisted at AECL. There was a perception among most AECL key informants that the committees continued to generate a significant amount of reporting burden at many staff levels, from project managers to senior management. It was said that monthly reporting took about two days of the project managers’ time (or about 10% of their time), in addition to the work involved in the quarterly and annual reports.

NLLP Delivery Model

Under the MOU for the NLLP, NRCan was responsible for policy direction and oversight, including control of funding, while AECL was responsible for identifying priorities and developing plans, implementing the program of work, and holding and administering all licences, facilities and lands. To implement the NLLP, AECL targeted efficiencies by using a matrix approach to allow for resource sharing between the branch in charge of decommissioning and other branches. However, AECL management generally agreed that the decommissioning branch was competing for resources and priority treatment with other AECL units, which caused delays, thus limiting the ability to secure qualified HR internally and the use of multiple contractors. Such challenges were raised by the previous evaluation,Footnote 21 and were still ongoing during the current evaluation period. For some projects, such as the HEU repatriation projects, AECL established integrated project teams so that all the resources needed for the successful delivery of the project were under the direct control of the project manager. However, other projects, such as the Fuel Packaging and Storage (FPS) project, secured resources through matrix management, and the consequent competition for HR resources within AECL caused challenges. In addition, AECL’s abilities to outsource work and hire staff were restricted due to the incoming GoCo model. Competition for resources was not an issue at Whiteshell Laboratories, as all staff at the site were focused on the decommissioning and cleanup of the site. As a result, NLLP site management was able to assign resources to projects and activities to maximize performance and program efficiency.

The 2011 evaluation recommended that the AECL update its procurement strategy, including a gap analysis of its current tendering mechanisms and a strategy to address the gaps. In response to this recommendation, AECL identified gaps and developed an action plan, which a subject matter expert in nuclear decommissioning and radioactive waste management concluded in April 2013 had been fully implemented. Nevertheless, this evaluation found that issues with procurement persisted for the remainder of the NLLP. For some projects, the procurement function caused significant delays, due in part to AECL’s expectations on the level of risk to be assumed by contractors. In some cases, this led to bids that were higher than expected, and in one case resulted in the extension of the bid period to revisit the balance of risk to be borne by the contractor and the federal government.

The 2011 NRCan evaluation also recommended that AECL continue to seek out the best technological, risk and cost benefit advice possible. According to NRCan staff, over the six-year period covered by this evaluation, the amount of work contracted out to third parties increased from 24% of annual expenditures in 2009-10 to 40% in 2014-15. AECL hired staff internationally to benefit from international experience in decommissioning and waste management. Examples include: an option assessment and feasibility study in 2009 that led to the decision to initiate a project to cement AECL’s inventory of stored liquid waste; a 2010 third party review of AECL’s five-year (2011-16) plan for the NLLP; the use of third-party contractors to prepare cost estimates to support the update to the liability cost estimate in 2012 and 2013; cooperation agreements with sister organizations in the United Kingdom, the United States, France and Spain to share best practices and lessons learned; and the use of a contractor with extensive international decommissioning and waste management experience to be the General Manager of the Whiteshell Laboratories Decommissioning Project for approximately 2 years (2011-2013). Despite these efforts, some AECL and external key informants expressed the view that the entire decision-making process, especially planning, would have benefitted from greater use of international expertise, given that this work had not been done in Canada before.

Financial Management

Most key informants generally said that the planning and budget-setting processes were adequate. As shown by the table 1, NLLP expenditures totaled $869.6 million between 2009-10 and 2014-15. These expenditures supported about 650 FTEs. Table 1 compares expenditures to the annual funding amounts approved by Treasury Board, and indicates annual variances ranging from a 3.6% underspendFootnote 22 to a 5.7% overspend, or a total underspend of $8.8 million for the six-year period, representing 1% of the total approved funding. The NLLP MOU included a provision that allowed AECL to carry forward unspent funds from one fiscal year to apply to eligible expenditures in the following fiscal year, and as a result, unused funding was carried over to be used in subsequent years.Footnote 23

| FY2009/10 | FY2010/11 | FY2011/12 | FY2012/13 | FY2013/14 | FY2014/15 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approved Funding | $116.0 | $128.3 | $129.4 | $137.6 | $172.1 | $195.0 | $878.4 |

| Actual Expenditures | $114.7 | $125.8 | $136.7 | $132.7 | $171.2 | $188.5 | $869.6 |

| Variance | $1.3 | $2.5 | -$7.3 | $4.9 | $0.9 | $6.5 | $8.8 |

| Variance (%) | 1.12% | 1.95% | -5.64% | 3.56% | 0.52% | 3.33% | 1.00% |

Source: NLLP Annual Reports.

Some external key informants nonetheless felt that more work could have been accomplished in the same timeframe, especially if incentives were offered.Footnote 24 The subject matter expert and AECL staff noted that no significant financial incentives were offered to complete work more quickly, despite the success in using incentives for the Rocky Flats site in the U.S. They noted that following the previous evaluation recommendation,Footnote 25 AECL explored the use of incentives.Footnote 26 NRCan key informants generally felt that it would not have been practicable for the Government of Canada to offer AECL financial incentives to clean-up its own sites, variously noting that:

- AECL’s procurement capabilities and capacity were insufficiently advanced to effectively engage a contractor on an incentivized basis;

- It would have been counter-productive for AECL to incent the decommissioning and closure of Whiteshell Laboratories prior to the completion of the AECL restructuring process, as one of the key objectives of the process was to put in place an incentivized “target-cost” contract to complete site closure within a 10-year period; and

- It would have detracted from the ongoing GoCo procurement process, as it might have reduced the options available to the winning bidder to complete the project in a timely and cost-effective manner.

Risk Analysis and Cost Estimation

The 2011 evaluation recommended that NRCan and AECL enhance risk management practices by updating the overall risk analysis and management framework at both the program and project levels, and that AECL implement a quantitative risk management system. In response, NRCan and AECL updated the program-level risk and control assessment on an annual basis, and AECL developed an action plan to improve project-level risk management practices. In April 2013, a subject matter expert in nuclear decommissioning and radioactive waste management and NRCan program personnel concluded that AECL had satisfactorily improved its project-level risk management practices.

For the current evaluation, all key informants confirmed that risk analyses were conducted at multiple levels to ensure that the decommissioning work focussed on the highest risk areas, and in accordance with a CNSC requirement for risk analyses. To that end, AECL maintains a Strategic Planning Risk Register to capture higher-level strategic risks related to program implementation, and Project Risk Registers for individual projects. AECL also implemented an Integrated Risk Management Framework in November 2012. While risk analyses are conducted to ensure the approach used for each project balanced safety considerations and project expenditures, AECL key informants noted that a further maturation of the analysis of risks at the project level was required to improve AECL’s quantification of risks.

As recommended by the 2011 evaluation, AECL analysed the cost-effectiveness of options being considered for major new NLLP projects. During this evaluation period, AECL applied a staged decision-making processFootnote 27 which is viewed by NRCan and AECL key informants to be the best approach as the focus is on projects where government would get the best value for its money. In some cases, projects were revised in light of new information affecting costs, including from responses to requests for proposals. According to a few key informants, the regulator (CNSC) also required AECL to calculate and submit cost estimates prior to starting a project. In 2013, it was decided that the NLLP would not undertake major new projects, and in particular projects to establish waste management facilities, to avoid potential actions that could constrain the GoCo contractor in implementing innovative and cost-effective long-term solutions. As such, the requirements for applying the updated pre-project initiation process, which included cost effectiveness analysis, to major new projects were limited. Some AECL key informants reported that cost-benefit analyses were not conducted systematically for all projects, and were of the opinion that AECL should have conducted cost-benefit analyses for more projects.

Waste Management

No long-term radioactive waste management or disposal facilities exist in Canada, and as a result, both legacy and newly generated radioactive waste at AECL sites needs to be stored until disposal facilities are available. The Nuclear Waste Management Organization is responsible, under the Nuclear Fuel Waste Act, to establish a national deep geologic repository for the long-term management of Canada’s nuclear fuel waste, including the used prototype reactor and research reactor fuel at AECL sites. The NLLP was responsible for identifying options, developing a strategy and advancing plans for long-term management facilities for AECL’s legacy low-level and intermediate-level radioactive waste.

In response to a 2011 evaluation recommendation, the Government of Canada’s approval for the second funding period for the NLLP (April 2011 to March 2014) required that a long-term integrated waste strategy be developed. It was expected that the government’s review of the strategy would occur in the fall of 2013, and that the NLLP would subsequently be in a position to take further steps based on the feedback received. AECL developed a waste disposal strategy that identified waste management facilities required to deal with the radioactive waste at its sites as part of an update to the liability cost estimate, which was completed in mid-2013. However, by that time, the initiative to restructure AECL was well advanced, and it was decided to defer decision making on the radioactive waste management facilities, to avoid imposing constraints on the GoCo in implementing timely and cost-effective long-term solutions.

Some key informants for the current evaluation noted that the delay in establishing long-term waste management facilities could increase overall costs, and reduce cost efficiency, because waste placed in storage during the NLLP will eventually need to be removed from storage, and characterized and potentially repackaged to meet the waste acceptance criteria for the waste disposal facility, once it becomes available.Footnote 28 Footnote 29

Project Management

Starting in fiscal year 2012-13, AECL implemented an Earned Value Management System (EVMS)Footnote 30 for the NLLP, and improved the underlying information (work breakdown structures, schedules and costs) over time as plans for completing the various projects and activities comprising the NLLP were better developed. The use of “Earned Value” to evaluate a project’s progress against budget and schedule is industry best practice, and AECL invested considerable effort in transitioning the NLLP to an Earned Value Management System. The work to support the EVMS with comprehensive and current project information was ongoing at the time the NLLP ended, with some projects described by detailed and up-to-date work breakdown structures and cost estimates, and other projects represented with outdated and less-detailed planning and cost information that was perceived to limit its utility. AECL informants also noted that AECL’s project management system was appropriate for reporting, although not user-friendly for daily use.

In 2014, AECL initiated a project to develop a new, integrated waste inventory database to consolidate and replace three separate, existing waste databases. Procurement of the required hardware and software was scheduled for early 2016, at the end of the NLLP. The new database is intended to be used to store both historic waste information, which reflects the requirements of the day for waste characterization, as well as the more comprehensive data for recently-produced waste, and the outputs and findings of legacy waste characterization initiatives.

Performance – Effectiveness

Taken together, the different lines of evidence demonstrated that the NLLP had made progress toward its expected immediate and intermediate outcomes. Specifically:

- NLLP delivery emphasized improved health, safety and environmental conditions at sites to satisfy regulatory requirements. All completed projects met regulatory requirements, and this was reflected in the program’s success in removing significant amounts of buildings and infrastructure and in achieving the vast majority of planned milestones. For the three-year second phase, which ran from April 2011 to March 2014, 93% of planned milestones were completed, and in the subsequent fiscal year (2014-2015), 94% of planned milestones were achieved.

- Improvements to legacy waste management were observed through facility clearance (at Chalk River and Whiteshell Laboratories) and HEU repatriation. Progress was made with FPS and SLWC projects, and in the last two years of the NLLP, the program of work was modified to incorporate new initiatives to support a smooth transition to the GoCo management model.

- It was generally felt that strategic decisions guided NLLP implementation toward risk and liability control and reduction by focussing on higher-risk infrastructure. A number of examples that risks have been reduced were documented in the evaluation, and NRCan informants noted that the liability reduction resulting from the implementation of the NLLP was taken into account annually as part of the update to the liability cost estimate in the Public Accounts. In retrospect, and despite that no such requirement was imposed by the Treasury Board, the absence of targets made it difficult to quantify risk reduction in the context of the current evaluation.

- The program supported better costing and an increased understanding of the liabilities through improved waste and site characterization data to support risk and cost estimates, changes in decommissioning plans, and the advancement of decommissioning work. Also, the liability cost estimate was adjusted to account for an increased attribution of indirect costs (e.g., corporate support costs and operating costs for the CRL site) to the NLLP.

- Finally, mechanisms were developed as a means for stakeholders and Aboriginal groups to be aware of and provide input to the program. Representation from Aboriginal groups was included on the Environmental Stewardship Council, a Communication Plan was developed, and the CNSC was satisfied with efforts to keep the public informed of and disclose activities at CRL. However, a conscious decision was made in 2010 not to pursue the intermediate outcome “Public confidence in and support for the long-term strategy” to avoid imposing constraints on the GoCo contractor.

Improved Health, Safety and Environmental Conditions at Sites and compliance with Regulatory Requirement

The NLLP’s priorities in building and infrastructure removal, legacy waste management and site remediation were described in Project Briefs for Treasury Board that secured Program approvals and funding, and included specific milestones to monitor progress and measure performance. For the three-year funding period from April 2011 to March 2014, 78 of 84 planned milestones (93%) were completed,Footnote 31 and 51 of the 54 (94%) milestones due in fiscal 2014-15 were completed by the end of March 2015. Findings from the document review revealed that those delivered milestones led to the completion of planned outputs, including several decommissioning projects that made lands and building/infrastructure space healthy and safe for other purposes. For example:

- The site of the former Glace Bay, Nova Scotia heavy water plant, which was contaminated with non-radioactive contaminants only, was remediated, and turned over for reuse.

- At Chalk River Laboratories, a pool test reactor was decommissioned and the room it occupied was returned for reuse.

- The Heavy Water Upgrade Plant was decommissioned, including the removal of all process systems and equipment, and the remaining building was being considered for reuse.

- At Whiteshell Laboratories, certain areas of the Shielded Facilities were decommissioned, including the 1300m2 Immobilized Fuel Test Facility, and its five Warm Cells. The area was repurposed for centralized waste management equipment and facilities.Footnote 32

- The Underground Research Laboratory (URL) near Pinawa, Manitoba was decommissioned and closed, the surface facilities were removed and the surrounding lands were restored, which permitted AECL to return the site lease to the Province of Manitoba.Footnote 33

- A strategic decommissioning plan was developed for the Whiteshell Laboratories site that accelerated the decommissioning and removal of the Main Campus buildings to 2028, which was ten years earlier than the previous plan.

All lines of evidence indicated that all completed projects met regulatory requirements, which according to interviews with the CNSC, are consistent with world standards. In particular, some key informants noted that CNSC signoff is a condition to maintain the licences associated with the sites. In addition, CNSC signoff is required for projects to be deemed completed, thus further helping to ensure completed projects meet regulatory requirements. For Chalk River Laboratories and Whiteshell Laboratories, CNSC staff’s assessments and inspections confirmed that:Footnote 34

- no worker or member of the public received a radiation dose that exceeded the regulatory limit;

- the frequency and severity of injuries/accidents involving workers were minimal;

- no radiological releases exceeded the regulatory limits; and

- AECL complied with its license conditions.

Improved Legacy Waste Management

Progress was observed in terms of legacy waste management, including efforts to reduce the volume of waste that needed to be managed as radioactive material at AECL sites. In particular, waste clearance facilities were established at Chalk River Laboratories and Whiteshell Laboratories to monitor likely clean waste in order to confirm that it can be recycled or disposed of as non-radioactive.Footnote 35 Waste management related outputsFootnote 36 at the Chalk River Laboratories and Whiteshell Laboratories included:Footnote 37

- Over 80,000 m3 of waste cleared, thereby providing cost-effective routes to reduce legacy waste inventories;

- A waste handling and characterization facility consisting of two compactors and an automated gamma waste assay system was established at Whiteshell Laboratories;

- Mobile waste characterization capabilities at CRL to support infrastructure decommissioning and environmental restoration projects; and

- A shielded aboveground waste storage building with a capacity of 4,000 m3 and a contaminated soil storage compound were constructed at Whiteshell Laboratories to manage the waste that will be generated in decommissioning the site.

Waste management activity was also observed at other sites. The highly-enriched uranium (HEU) repatriation project, the Fuel Packaging and Storage (FPS) project and the Stored Liquid Waste Cementation (SLWC) project each demonstrated progress to improve waste management, as detailed by their respective case studies presented in Appendix C. While the HEU project was slightly behind schedule because of unanticipated US regulatory requirements, used HEU fuel was delivered to the US as per the US-Canada agreement.Footnote 38 As for the FPS and SLWC projects, both of which were ongoing when the NLLP terminated, early findings suggest they are also contributing to improved legacy waste management. The 2011 evaluation findings indicated that the FPS Project was at least three months behind the schedule that had been developed four years before. AECL discovered a number of design errors and omissions that resulted in schedule delays, and were a major contributor to the cost overruns.Footnote 39 During the current evaluation period, the FPS project challenges were resolved, and AECL received approval from the CNSC to operate the FPS facility in 2014.

The SLWC project was initiated in 2009 to retrieve and solidify the legacy liquid waste and sludge in twenty (20) aging tanks at Chalk River Laboratories that were constructed in the 1950s and 1960s. Between 2010 and 2015, the project successfully made progress as follows:

- Recovery and transfer of the bulk liquid waste in seven (7) tanksFootnote 40 with low-level activity to the CRL Waste Treatment Centre for volume reduction and immobilization. The solid sludge material in the tanks will be addressed at a later stage of the project.

- Liquid content was retrieved from an eighth tank on a priority basis to address the risk of the tank leaking and causing environmental contamination, because it was the only tank without secondary containment. The tank contents were pre-treated before transferring them to the CRL Waste Treatment Centre for volume reduction and immobilization.

- Project proposals were received (including conceptual designs, schedules and costs) to retrieve and cement the liquids and sludge from the remaining twelve (12) tanks with higher activity-level waste, as well as the residual sludge in the previously-discussed eight (8) tanks.

While there is no permanent long-term storage facility, NRCan documentation showed that plans for a very-low-level waste disposal facility were well advanced under NLLP, including the completion of detailed designs for two potential sites at Chalk River Laboratories to accept low-contamination materials and soils from the decommissioning of buildings and the clean-up of contaminated areas. However, NRCan interview findings indicated that the decision was made to leave it to the winning bidder of the GoCo procurement process to decide whether to proceed with the project. Similarly, the conclusions of a Third-Party Review to support decision-making on whether the CRL site would be a technically suitable location for a geological waste management facility were optimistic. The report’s recommendations were grouped into two categories: short-term actions considered necessary to complete the site suitability assessment; and a long-term work plan for site characterization, assessment and evaluation.Footnote 41 When the NLLP ended in September 2015, AECL was targeting completion of the short-term actions by March 2016.

Strategic Decision Making to Guide Program Implementation

Most NRCan and AECL key informants agreed that strategic decisions guided NLLP implementation toward risk and liability control by focussing on higher-risk infrastructure, including high hazard buildings and wastes. Although it is difficult assess the progress in risk reduction, as no targets were established or ever required by Treasury Board, there is documented evidence that risks have been reduced, including the following examples:Footnote 42

- More than 30 buildings at Chalk River Laboratories (CRL) in Ontario and Whiteshell Laboratories in Manitoba were decontaminated, decommissioned and removed.

- At Chalk River Laboratories, several projects reduced risks and liabilities. The Waste Management Area “C” is closed and contains a large volume (approximately 100,000 m3) of buried low-level radioactive waste. Installation of a multilayered engineered cover was completed in September 2013, and final landscaping of the site was completed in November 2013. This has reduced water infiltration into the Waste Management Area, and limited the further spread of groundwater contamination.

- Fieldwork to remove metal waste items at the CRL Bulk Storage Compound was completed in 2012-13. In 2013-14, soil sampling and radiation survey verification activities demonstrated that the cleanup criteria for the compound had been met. All waste suitable for off-site treatment and disposal has been shipped offsite for processing.

- Environmental risks were removed or reduced at more than 20 discrete contaminated areas at CRL and Whiteshell Laboratories. Higher-hazard buried wastes, such as used fuel rods and liquid waste were retrieved at CRL. Groundwater treatment at CRL was also improved with the addition of a new groundwater treatment system.

- AECL’s inventory of oils and solvents with radioactive contamination, which totaled approximately 180,000 litres, was shipped off site for incineration, and more than 1,000 tonnes of ferrous metal and lead was sent to metal melt facilities for reuse in the nuclear industry.

- Over a two-year period, a total of 22,800 liters of liquid waste from seven legacy tanks was treated in the Waste Treatment Centre at Chalk River Laboratories and a further 34,000 litres of waste was removed from an eighth tank in 2013 and 2014 for treatment.Footnote 43

Understanding of the Liabilities

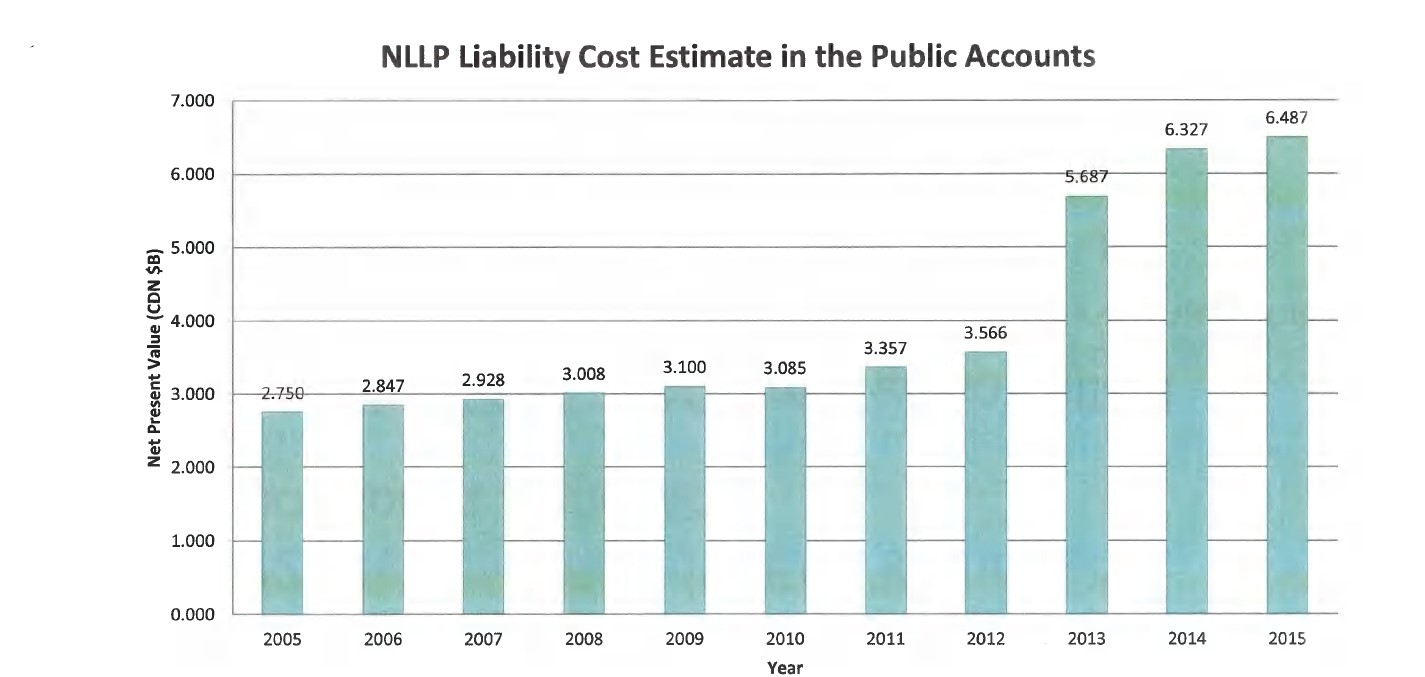

The federal government’s nuclear legacy liabilities comprise aging nuclear facilities and associated infrastructure, a wide variety of buried and stored waste, and contaminated lands. Figure 1 provides an overview of the trend of the liability cost estimate in the federal government’s Public Accounts in net present value, showing that the value increased significantly from $3.100B to $6.487B, from 2009 to 2015.Footnote 44 It was recognized at the outset of the program in 2006 that over time, the Net Present Value cost estimate would increase as the government’s understanding of the liabilities increased for various reasons, including: improved waste and site characterization data; changes in the decommissioning plans; updated cost-estimates based on better information; and revisions to AECL’s activities that could lead to the advancement of decommissioning work. The influence of these factors is reflected in the gradual increase in the liability between 2005 and 2012. The more significant increases in subsequent years (2013 to 2015) were due to the increased indirect costs attributed to the program, including AECL's corporate support costs and the costs to operate the CRL site.

Figure 1: Liability Cost Estimate

Text version

Y-Axis Net Present Value (billion Canadian dollars). X-Axis, year. 2005 2.750 billion dollars; 2006 2.847 billion dollars; 2007 2.928 billion dollars; 2008 3.008 billion dollars; 2010 3.085 billion dollars; 2011 3.357 billion dollars; 2012 3.566 billion dollars; 2013 5.687 billion dollars; 2014 6.327 billion dollars; 2015 6.487 billion dollars.

The expected outcome related to an increased understanding of the liabilities has been achieved through the production of characterizationFootnote 45 information, and various risk analysis and cost-estimates. According to best practices identified in the literature (e.g., Taboas et al., 2004), assessing risks and estimating decommissioning costs (i.e., costing of the liability) is based on proper “characterization” information (i.e., knowledge of the radioactive inventory in the systems, components and structures)Footnote 46 and various cost-estimates. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)Footnote 47 indicates that waste characterization is typically developed from a range of requirements related to disposal performance assessment, waste acceptance criteria, process control and quality assurance, transportation, and worker safety. Furthermore, in cases where no mature disposal concepts are established, one has to presuppose future disposal requirements. However, the IAEA notes that “such a situation inherently contains much more risk, given that overlooking parameters may have severe monetary consequences. It will also be difficult to predict what level of analysis will be required to satisfy the regulator.”Footnote 48

During the NLLP, waste, building and site characterization data was collected for many of the projects and activities undertaken. Characterization work was required for all building and infrastructure decommissioning projects and all site remediation projects to protect workers and ensure proper handling and management of the radioactive waste generated by the clean-up work. Initiatives to send legacy waste offsite for treatment or disposal also required comprehensive characterization information to confirm that it met the waste acceptance criteria of the receiving organization. In addition, characterization of affected lands and buried waste areas was conducted to understand the extent of the cleanup that will be required in the future.

As a rule, legacy waste that was buried or stored in early-generation structures that did not provide for easy access to the waste was not disinterred for characterization because:

- AECL had not yet established waste acceptance criteria for its planned disposal facilities, so there was no basis for determining the types of radionuclides or the activity levels against which the wastes would be analyzed.

- After characterization, AECL would not have been able to return the waste to the outdated storage facilities. Rather, the waste would need to be stored in the newer, aboveground concrete storage facilities, which would reduce the available storage space for newly generated waste.

Views about the types and quality of the characterization work conducted under NLLP were varied but all agreed that this work contributed to the implementation of NLLP projects. While most respondents generally agreed that characterization conducted for decommissioning was appropriate in the context of the incoming GoCo, some AECL respondents felt that AECL should have completed more characterization work to understand the requirements for waste disposal facilities. According to those informants, characterization work should have been based on typical waste acceptance criteria from the literature for the planned waste disposal facilities. NRCan informants noted, however, that the GoCo’s planned approaches and facilities for disposing of radioactive waste are different from those under AECL’s previous waste disposal strategy under the NLLP, and thus it is not clear that waste characterization based on assumed waste acceptance criteria for those types of facilities would be applicable to the GoCo contractor’s waste disposal strategy.

Stakeholders and Aboriginal Groups awareness, Input and Confidence

Evidence from the literature review confirmed that demand for information and for participation, as well as public scrutiny of the nuclear industry, has increased over recent years (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2010). Key informants and file review findings indicated that NRCan, AECL and CNSC each developed mechanisms, and conducted awareness and engagement activities related to decommissioning and site cleanup projects that targeted NLLP stakeholders and aboriginal groups. Examples include:

- NLLP website was launched in 2010 to provide another avenue for the public to access videos, information sheets and other information on the Program. The website was later improved and relaunched in May 2014 and was continuously updated throughout the year.Footnote 49

- Community newsletters were distributed to local stakeholders in the areas surrounding AECL sites at Chalk River Laboratories and Whiteshell Laboratories.

- AECL and NRCan held Open Houses, information booths, public information sessions and other community events, providing the opportunity for local residents, the public and stakeholders to view information, share their interests and concerns, and ask questions about the NLLP.

- A Joint NRCan-AECL Sub-Committee and Working Group were created to oversee the development of communications plans and materials. A High-Level Communications Plan approved in June 2013 outlines different approaches to meet the NLLP communication goals and enhance stakeholder confidence.

- Information on the NLLP was provided through updates made to the Chalk River Laboratories Environmental Stewardship Council and Whiteshell Laboratories Public Liaison Committee at their regular meetings. Further, specific steps were taken to engage Aboriginal communities in Chalk River Laboratories developments, including by ensuring there is representation from Aboriginal groups on the Environmental Stewardship Council.Footnote 50 CNSC documents list the Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation as a First Nations group that was consulted.

- When First Nations and Metis did not attend the Whiteshell Public Liaison Committee meetings, AECL took additional steps to ensure engagement. For instance, AECL sent them documentation and job postings for their information.Footnote 51

- During the bridge period while working towards GoCo, the NLLP used communications activities to inform decision-making and to build understanding among individuals, groups and organizations that have a stake in the NLLP, so that activities might move forward in a timely and effective way. Following the implementation of the GoCo management model, the information on NLLP activities was relocated to CNL’s external website.Footnote 52

NRCan key informants advised that a conscious decision was made in 2010 not to pursue the intermediate outcome “Public confidence in and support for the long-term strategy” (see NLLP Logic Diagram, Appendix A), because of the requirement to first seek government feedback, in late 2013, on the options for radioactive waste treatment and disposal facilities to address the legacy waste. In the latter two years of the NLLP, engagement activities on the long-term NLLP waste strategy were not undertaken to avoid imposing constraints on the GoCo contractor, as it was recognized that the contractor could propose a different suite of waste treatment and disposal facilities to safely address the legacy liabilities in a timely manner.

Conclusions and Lessons Learned

The NLLP was clearly needed to address the social and environmental risks and liabilities associated with contaminated lands and infrastructure. It was also aligned with domestic and international standards for the management of nuclear waste, and with federal roles, responsibilities, and priorities.

A number of program components generally contributed positively to the efficient delivery of the NLLP, including:

- adequate governance and clearly delineated roles and responsibilities for NRCan and AECL;

- a planning and budget-setting process that allowed the carry forward of unspent funds;

- the use of an Earned Value Management System to better evaluate project progress against budget and schedule;

- the conduct of risk analyses at multiple levels, and the application of a staged decision-making process to assess value for money and develop lifecycle cost estimates prior to starting projects;

- the use of external experts (e.g., for waste management and decommissioning); and

- an integrated waste inventory database to store both historic and new waste information, as well as legacy waste characterization information.

Other components of the program were found to impede efficient delivery, such as a matrix approach for resource sharing at AECL which caused competition for resources, delays, and reduced access to human resources for some projects. Also, AECL’s expectations of the level of risk to be assumed by contractors may have sometimes contributed to bids that were higher than expected and in at least one case, to an extension of the bid period to revisit the balance of risk to be borne by the contractor and the federal government.

Certain aspects of the NLLP’s operational context affected the program’s priorities and progress in working toward its original intended outcomes in order to support broader Government of Canada objectives and initiatives. Notably, the transition to a GoCo model was variously perceived to restrict the program’s ability to outsource work and hire staff, and was also a factor in the conscious decisions to no longer initiate new major projects. Furthermore, while the NLLP advanced planning for long-term management facilities for legacy low and intermediate-level radioactive waste, it was decided to defer decisions on implementing the projects to avoid imposing constraints on the GoCo, recognizing the potential for overall costs to increase due to future requirements to retrieve and possibly repackage the stored waste.

The NLLP made progress toward all of its expected immediate and intermediate outcomes, as variously demonstrated by: full compliance with regulatory requirements; waste clearance and shipment of waste for processing and disposal in the U.S. from several sites; risk reductions through a focus on infrastructure decommissioning; improved waste and site characterization data to support risk and cost estimates; and the development of various mechanisms to engage stakeholders and Aboriginal groups. Over 90 percent of program milestones were achieved over the final four full years of program implementation (fiscal years 2011-12 to 2014-15).

Lessons Learned

Based on the evaluation findings, the following lessons were learned:

- Multiple accountabilities create challenges for program oversight.

Under the NLLP, NRCan had ultimate responsibility for the program, but did not have the authority to set program priorities for AECL, because AECL owned and was ultimately responsible for the waste liabilities. The GoCo management model addresses these challenges in that AECL has full latitude to set priorities and objectives for its GoCo contractor to achieve reductions of risks and liabilities. Further, as a Crown corporation, AECL delivers on its mandate and missions at arms-length from the Government of Canada, and so can leverage private sector capacities to implement an innovative, timely and cost-effective program of work to meet AECL’s objectives. - Potential efficiencies of matrix resource allocations can be offset by delays resulting from a competition for resources.